When Barack Obama entered the final week of his presidency last month, he granted clemency to 603 people, including high-profile convicted leaker Chelsea Manning and former Studio 54 co-owner Ian Schrager. And he rounded out his time in office having granted commutations to a total of 1,715 prisoners — the most by any one president in U.S. history.

The clemency power is an act of mercy outlined in the Constitution. It gives the president the authority to commute the sentences of federal prisoners, either totally or partially, and as a gesture of forgiveness, pardon people following their conviction, or after they’ve served their time. Over the years different presidents have used their clemency power to different extents: George W. Bush granted clemency to 200 people during his two terms in office, while Roosevelt did the same in a single year.

While Obama touched on his efforts to “reinvigorate the clemency power” in a lengthy piece recently published in the Harvard Law Review, it’s an authority we had not really seen him flex until the past few years. Before October 2014, he had only granted 10 commutations, but to his credit, that year also brought with it a significant change. Under Obama’s directive, the Department of Justice announced the clemency initiative — essentially an invitation for federal inmates who fit a certain profile to petition to have their sentences commuted by the president.

With many prisoners serving overly long sentences due to mandatory minimums and sentencing enhancements established by decades-old law, this was a way — albeit not a long-term one — of freeing some of those who had been languishing behind bars for years from a broken system. The clemency initiative outlined stringent criteria, including that had the applicant been sentenced today, they would have received substantially less time, that they had served more than 10 years of their sentence, and that they had demonstrated good conduct while inside prison, with no history of violence during or outside of it.

After the announcement, over 36,000 inmates — nearly 17 percent of the federal prison population — responded to the invitation and sought help to file. And out of over 33,000 prisoners who actually did apply over the past few years, only 5 percent were successful.

In his life before prison, Keldren Joshua, 45, worked day jobs for Bank of America and American Apparel near his home in East Hollywood, and DJed and ran a radio show on the side. He smiled while talking about the time when he could tell you what was going on in Los Angeles on any given night or day. “I was the social media guy before there was social media,” he said.

Out of over 33,000 prisoners who applied for clemency over the past few years, only 5 percent were successful.

In 2005, Joshua told me that he got caught up as a middleman in a meth deal. He was convicted of conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute a controlled substance. Joshua knew he deserved to be punished, but he hoped that as a first-time offender with a criminal history of little more than a bunch of traffic tickets, he’d be looked upon favorably. “When the judge says, ‘We’re sentencing you to 188,’ I thought that was days, but my lawyer’s over there doing 188 divided by 12,” Joshua said. “15 years. 8 months. I looked at the judge. I turned pale. I’m like, what? On a first offense?”

Eight years into his sentence, Joshua received a package from the federal defenders’ office in Los Angeles saying they thought he was a good candidate for Obama’s clemency initiative. With the help of federal defender Andre Townsend, he applied. And on August 3, 2016, nine years and eight months after he first arrived at the Terminal Island prison in Los Angeles, Joshua found out he was going home.

“I genuinely see how clemency was granted to this person,” said Townsend. “Quite frankly, I could see that he had over-served his sentence, and he had done a great deal of work while in prison to rehabilitate himself, and to prepare himself for a productive return to society.”

Since getting out, Joshua’s taken up a job at a shoe store in Santa Monica and is picking up his efforts to get back into music and media. He avoided using any words of resentment to describe his time in prison. The only time he hinted at hardship was when I asked if the the years he spent behind bars had gone fast. Joshua pressed his lips together and shook his head.

Clemency is one tactic that Obama used to address the legacy of mass incarceration in America. As he and White House counsel Neil Eggleston have both said, it’s a tool of last resort in fighting a system that puts people away for extended lengths that far outweigh their crimes. It has the power to change the life of an individual, but only Congress can bring laws into effect that create change on a larger level.

“I think that Obama has been one of the most active voices for criminal justice reform,” said Mary Price, the general counsel of FAMM (Families Against Mandatory Minimums), one of the most visible sentencing reform advocacy groups in the country. “He has talked about criminal justice in a way that no other president that I can remember in my work has.”

Clemency isn’t without its problems or critics. “I think clemency was Obama’s way of performing triage on the broken criminal justice system, and for that I respect him tremendously,” said Amy Povah, founder of CAN-DO, a clemency nonprofit with a particular focus on advocacy for women. Povah received clemency under Bill Clinton in 2000 after serving 9 years of a 24-year sentence as a first-time offender for her involvement in her then-husband’s drug ring. “But we are the world’s leading incarcerator. I don’t think it’s time to take a victory lap about going down in history yet, when all these people were invited to participate. It’s like throwing a big party, sending out 30,000 invitations, and everybody’s waiting to get in.”

There have also been signs of internal discontent surrounding the clemency process. Last year pardon attorney Deborah Leff resigned from her position, citing an office starved of resources, which made it difficult to act in line with Obama’s wishes. She also mentioned that unlike previous administrations, she was denied “all access to the Office of White House Counsel” by the Department of Justice, the point of last review before the application is considered by the president. Leff pointed to instances in which petitions that had been recommended by her office were reversed by the DoJ and didn’t make it to the White House. “Obama can only grant the ones that make it to his desk,” Povah said.

After serving more than 21 years in prisons in Kansas, Colorado, and California, Fulton Washington was one of 58 prisoners who had their sentences commuted by Obama in May 2016. “I was pretty much speechless when I found out,” he recounted. “So many things had been denied over the years that it didn’t even seem like a reality at the time.”

The now-62-year-old grandfather from Compton, California was convicted of 3 nonviolent drug offenses in 1996 related to PCP. Due to a mandatory minimum triggered by three nonviolent priors, the judge was required to give Washington a life sentence.

“I was pretty much speechless when I found out.”

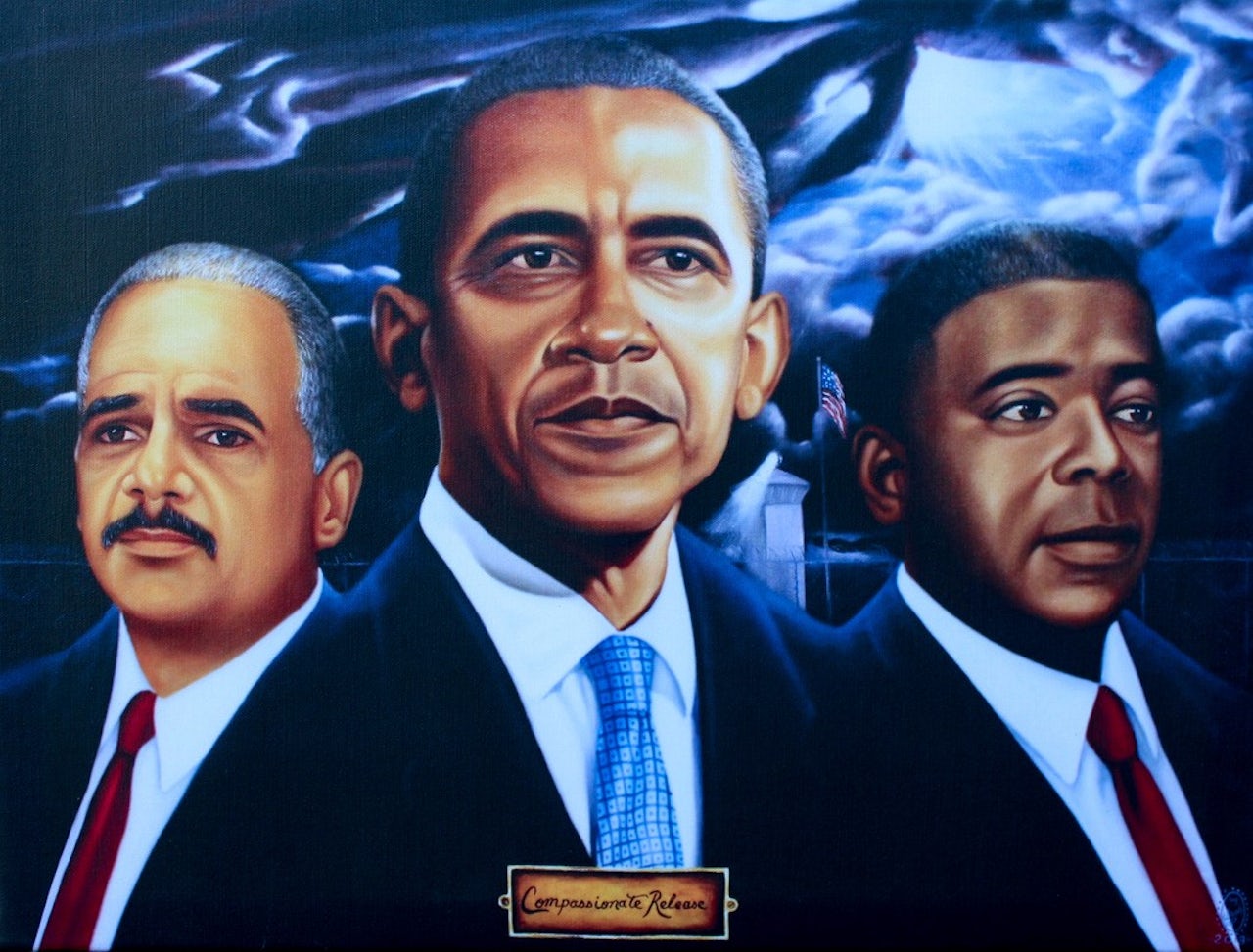

Washington says that he simplified his life into three areas while in prison — prayer, working on his case, and painting. He started concentrating on art following his trial in 1997, when his attorney asked him to draw the witness who could help corroborate his story. He drew a composite sketch so accurate that his defense team was able to find the person, who testified in his defense.

“I made a promise that day that I would continue to practice the gift that He gave me, and I would share that gift,” Washington said. “So I continued to teach art and practice art. And it evolved into what we see today.”

Throughout his two decades of imprisonment, Washington painted thousands of hyper-realistic portraits and scenes, both real and imagined. Some captured moments and memories for fellow inmates. Three adorn the walls of the Lompoc Veterans’ Memorial Building in Santa Barbara. Washington said he was approached in 2013 to be part of the pilot program that evolved into Clemency Project 2014, an inter-organizational pro bono effort. With help from a participating attorney, Washington filed a petition, which Obama granted in May 2016. Washington left for a halfway house in June, and was officially released in September.

Washington spent 21 years imagining the day someone would tell him he was free, but when he finally he heard the words out loud, the experience was jarring. “It’s like after living in a bathroom for so long that a person’s telling you that you can leave,” he said. “Leave and go where? And do what? It really didn’t dawn on me that I was free until I started to experience it.”

Unlike Washington and Keldren Joshua, Schearean Means didn’t have a clemency lawyer and worked with a CAN-DO representative on her commutation application. Convicted in 1996 of nonviolent drug offenses involving crack, cocaine, and marijuana, she was sentenced to life in prison due to a combination of provisions in the law and two minor priors. “When the judge said life,” Means remembered, “I thought I was a dead person.”

Now in her early 60s, Means was granted clemency on December 19 of last year, when Obama commuted the sentences of 153 and pardoned 78 more. According to Amy Povah’s count, Means is one of 106 women who have had their sentences commuted by Obama. This rate more or less matches the statistics for women currently in federal prison, who make up 6.7 percent of the overall population.

Moving slowly following an operation for breast cancer, Means called from a payphone inside FCI Aliceville, a low security women’s prison in Alabama. Her sentence was officially reduced to 30 years with a release date in 2021, but with a combination of good time credit (for good behavior) and an application for a sentence reduction, she hopes to be out sooner. “When I found out I just screamed and dropped down on my knees and said, ‘Thank you, Lord, for helping me,’” she said, “‘for taking life off of me.’ I screamed so loud.”

When Obama left office, so did his clemency initiative. Means made it just in time. There are many prisoners who fit the clemency initiative’s criteria but had their applications denied. Nearly 9,000 prisoners never received an answer.

“I am extremely disappointed with the end result,” said Povah. “Many first offenders with exemplary conduct who have served 10-plus years — some more than 20 years — were passed over. These prisoners were led to believe if they met all the criteria, they would receive clemency. To deny those petitioners is an outrage.”

Even beyond just those who applied to have their sentences reduced, there are thousands more in federal prisons across the country whose punishments far outweigh their crimes. Despite its shortcomings, the clemency initiative was one way for Obama to directly affect a small number of individuals — 1,715 people — by pulling them out of a system that’s failed them. He granted an historic number of commutations, which is a milestone celebrated by those released that conversely won’t mean much to the people who remain.

After announcing himself as president with a frenzy of activity, there’s a general air of uncertainty around how Trump and his administration will handle clemency. “I am hoping that Trump is going to want to prove himself to his naysayers,” Povah said. “But it all depends on who he listens to, and if he’s going to surround himself with a certain mindset. If we can’t penetrate it and we don’t get a seat at the table, it’s going to be devastating.”