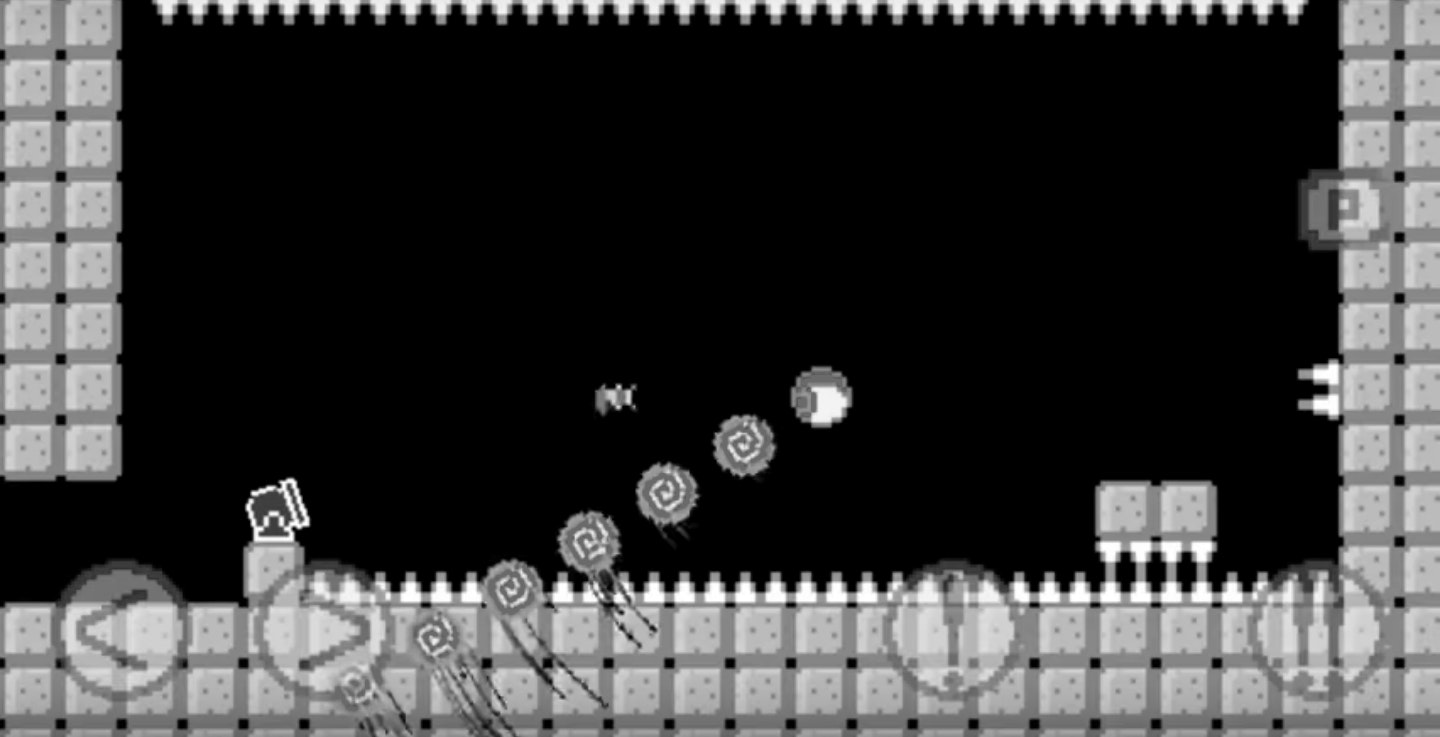

A malfunctioning CRT sends ripples around the edges of the display. Static crosses a face momentarily; a diffuse, ominous presence looming over a stuttery, digital megalopolis. A character appears, pixels painting him onto the screen. Battles ensue. A game within a game takes shape. A version of our reality blooms, not nearly realistic, but familiar. The home aesthetic. The foundation and the future. Narita Boy — a new Kickstarter video game project — is where we’ve always been, and where we’ll always be going. It’s another signal that what lies up ahead in gaming (and by proxy, in art) is going to feel strikingly similar to what we’ve left behind.

The 8- to 16-bit retro gaming trend is not new. Developers have been mining this history for decades now, our 3D futures being traded for pixelation and screen burn-in. Chiptune artists have been repurposing Game Boys (or at least their sound generators) to make surprisingly modern music, and even early Flash web games drew on the influences of the NES and its kin to build something new, yet aggressively... comfortable? These creative concepts naturally spread into the art world, seen in Cory Arcangel’s 2002 piece Super Mario Clouds and works like the psychedelic collages of Paul Robertson. The look has won a slow war elsewhere, seeping into everything from movies like Wreck-It Ralph and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, to fashion, with Moschino’s Super Mario Bros. capsule collection and the flat-out pixel art of Anya Hindmarch’s Autumn / Winter 2016 line.

Hell, the most important video game of this generation is, in many ways, a throwback. Minecraft wouldn’t exist if a world made of obvious pixels hadn’t been realized and then rehashed a thousand times over.

A generation of kids who lived through the gaming boom of the ’80s are now the CEOs, developers, and designers at some of the most respected gaming houses. So it makes sense that the place where this retro-future is best expressed and best understood — outside of works of fiction like Ready Player One (perhaps the first piece of retro-future video game literature) — is in our gaming universes. Where the possibilities are increasingly endless, but they look and feel more and more like something we’ve seen before. Games like Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, The Incident, and what seems like half of the titles on the App Store have taken the flatness of Metroid and Mega Man and reworked and recalculated the style into something wholly new. It's this fused sensibility that gives the games ballast. That makes them “right.” Like Paul Atreides on the surface of Arrakis in Dune, it’s a place you know even though you’ve never been there before.

Like mid-century modern furniture and architecture, the styling of “retro” games has become something more than a trend. It's become a baseline.

But what makes Narita Boy so immediately stirring isn’t just its reliance on historic art and tone, but the fact that its storyline seems to play out on a meta level, blurring the line between the game’s fiction and its fictional reality. Watching the trailer, you’re struck by how something so basic can emote something so… intense. A world thick with the rhythm and depth of the greatest mindbenders in literate sci-fi or auteur filmmaking. But a world only possible in a new age where technology is scenery and the remix is the hit single.

Okay, maybe I’m getting ahead of myself. The Kickstarter project hasn’t even reached its funding goal yet. But at the same time, I can’t help but be energized by projects like Narita Boy, Hyper Light Drifter, and even the brainless gore of Hotline: Miami. There’s something expansive in their aesthetic, something endless. A feeling of freedom that seems to come from an embracing — or smashing — of the limitations and lines set out a long time ago, by people who maybe didn’t set out to make art, but ended up mapping a whole new creative world.

Sure, games have gotten more realistic. It’s likely that in just a few years we won’t be able to tell what’s computer generated from what is not. But the beating heart of what games really are will always be rooted in a past. A past that imagined the future, then made it real.