Drake is not woke. He has had more girlfriends than I know people, a fact made evident by his propensity to name many of them on record. Also on record, he has patronized said women, counted their previous sexual partners, and claimed ownership of them. He is tepid on matters of racism, or, alternatively, is too cowardly to publicly say otherwise. (His longtime producer, business partner, and friend 40, who functions like somewhat of a moral conscience for OVO, has spoken out plainly in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.) Drake’s singing voice — though it has improved dramatically in recent years, under the guidance of vocal coach Dionne Osborne — can sometimes feel like taking a cheese grater to your eardrum. On certain songs, his retreaded backpacker flow can be awkward to the point of inducing secondhand embarrassment; so can his self-indulgent, self-pitying navel-gazing. For a while, there was a bizarre obsession with the late Aaliyah, who is immortalized on his back in a very large tattoo. Oh, and, he counts a domestic assaulter among his friends.

These are all perfectly reasonable and understandable reasons to dislike Drake. At least one of them would demand that fans, at the very least, question his character. But, bizarrely, much of the conversation and fever-pitch criticism surrounding the release of his latest project, More Life, has focused elsewhere: Accusations of inauthenticity and “culture pillaging” have, at least informally, dominated the narrative, throwing some corners of the social web into what’s been half-jokingly termed a “diaspora war.” They’ve also exposed the limits of the widening conversation about appropriation.

Rather than a traditional album, More Life is billed as a playlist. There are likely technical and cultural reasons for this. But it also offers an insulation from the expectations of a capital-A album, in the way that describing 2015’s If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late and the full-length Future collab What a Time To Be Alive as mixtapes once did. The playlist landed with an 808 thud on Saturday. En gros, it makes good on the global pop promise he’s made over the past couple of years: Across 22 tracks and 81 minutes, Drake delivers a wide range of sounds and modes. Most of it is very good. In just 24 hours, More Life was reportedly streamed close to 90 million times on Apple Music alone. Last year’s Views, which had a five-day Apple Music exclusive, was streamed 245 million times on the platform — in one week.

Throughout, there are samples and guest appearances from a cross-section of genres: Moodymann, Hiatus Kaiyote, Black Coffee, and Lionel Ritchie, for example. There’s also more Classic Drake — weaving between pithy R&B numbers and traditional, introspective, bars-first tracks — than anyone needs. Elsewhere, there are songs featuring U.K. rapper Giggs, grime MC Skepta, and British singer Jorja Smith.

But a stretch of songs early in the project — transparently designed to be blasted from passing cars all spring and summer — are clear standouts, both as tremendously enjoyable pop songs and as epicenters of the reception of More Life. “Get It Together,” “Madiba Riddim,” and “Blem” are conceptual follow-ups to last year’s radio smashes, “One Dance” and “Controlla,” on which Drake tested his reach as both an artist and a fan. Like those songs, the wind-friendly offerings on More Life draw sonic and melodic inspiration from parts of the Caribbean, Africa, and beyond.

The American and European context of which “cultural appropriation” is borne can erase the perspectives of people on whose behalf the claim is made.

Also like those songs, they’ve been characterized as amounting to “cultural appropriation.” The concept, and the phrase, of appropriation is important — among other things, it can be used to directly call out imbalanced racial, cultural, and power dynamics that allow a person or group to benefit from another person or group’s culture, while disrespecting that culture, distorting it, or dehumanizing the people who belong to it. In recent years, it moved from academia and into the mainstream, alongside words and concepts like “microaggression” and “rape culture.” Understanding the dangers of cultural appropriation has been instrumental in a broader movement challenging assumptions about what racism does and doesn’t look like.

But as the vocabulary has spread, it has occasionally become diluted from its original meaning and intent. Drake is the son of a man from Memphis, who arrived in Memphis because, at some point, at least one of his ancestors was stolen, shackled, and delivered to America. Drake is not Scarlett Johansson, who recently reached to justify her casting in the forthcoming Ghost in the Shell and subsequent erasure of the film’s Japanese origins. He is not the co-creator of Iron Fist, who had this to say when challenged on the series’ appropriation: “Don’t these people have something better to do than to worry about the fact that Iron Fist isn’t Oriental, or whatever word?”

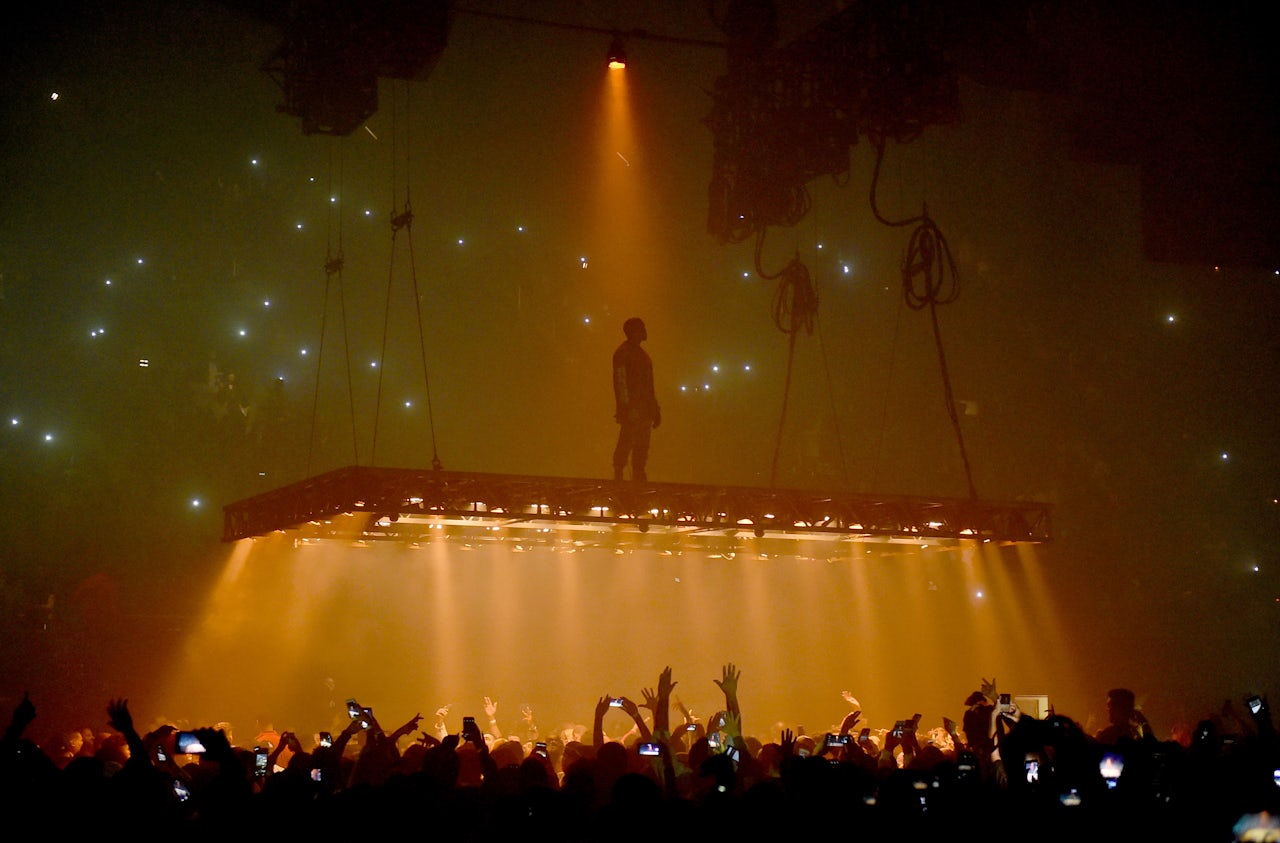

Instead, Drake’s use of Afropop or dancehall or South African house is in the direct tradition of diasporic intermixing that has long existed in music and elsewhere. In conveniently glossing over that, the naked claim of cultural appropriation prioritizes the perspectives and experiences of certain people over those of others. The American and European context of which “cultural appropriation” is borne can, even unintentionally, erase the perspectives of people on whose behalf the claim is made. For some of the non-American artists with whom he has collaborated — and for others working in those same genres — Drake’s interest has been received with enthusiasm. Plus, as the writer Amani Bin Shikhan observed in 2015, analyses of his work often ignore “the intricacy with which diasporic hoods flirt and intermingle with each other to create a context that rears its head on a cool summer night in the [A]ir [C]anada [C]entre as [D]rake takes the stage.”

On a good chunk of More Life, he sounds like the product of that intermingling: Toronto Drake is a character taken for granted by locals for years but was only introduced to the broader public during the rollout of IYRTITL. By that point in his career, Drake had successfully asserted himself as a powerhouse and was ready — and bulletproof enough — to try a ting. In that mode, he speaks and raps, like any one of my friends from home — when we’re not at work, or at school, or with our parents. His vowels are rounded and elongated, as if his tongue had become leaden. “Yo!” becomes “Yoooooooo, guy”; thoughts are punctuated by what feel like IRL ad-libs, like a high-pitched “jheeeze!” or a guttural “mm-hmmm!” When I feel especially homesick, I often watch a silly 2012 YouTube video, “Shit Toronto People Say,” that captures that distinct feeling; listening to Drake sometimes accomplishes the same thing.

And, yes, much of that vocabulary and culture is pilfered, and then reconstituted, from countries whose immigrants populate much of Toronto and whose language and traditions built its popular youth culture from the ground up — Jamaica, Trinidad, and, increasingly, Somalia. On any given day in the city or its suburbs, you’re likely to hear a single sentence bridge the thousands of miles between those places. Language, like people, is not static. Whereas “ting” in Jamaica simply means “thing,” in Toronto it has evolved to a somewhat more pointed usage. A “ting” can be a hot girl, a gun, or any pressing subject. In London, a comparable pattern of immigration and a national culture that encourages, perhaps disingenuously, multiculturalism led to a similar diasporic code.

Of course, the movement of people, culture, and language is complex. Language that may feel like a natural part of any given Torontonian’s culture has both real-world roots and real-world consequences: A dark-skinned Jamaican person who wears locs, for example, will be stigmatized and treated differently by law enforcement than a white, or South Asian, or North African person, for example. But one can respect those roots and respect that reality without erasing the cultural and historical forces that mean a biracial, Jewish, former child actor may be his authentic self while saying “ting.”

Which is perhaps why I bristle at the reduction of that as proof that he must “wish he was born Jamaican.” In his Pitchfork review of More Life, the writer Jayson Greene pointed to Drake’s shifting between “ting” and “thing” on one song as proof that he must be a fraud. This, and similar claims, are misreadings that reveal more about listeners’ biases than they do about Drake. As Bin Shikhan wrote in her 2015 essay, “[T]oronto is not a city that can be understood by non-[T]orontonians…” She added, “[T]he history of black [C]anada, let alone black [T]oronto, is not regarded as vital and need-to-know information.” There are a lot of things to learn about the city and a lot of frustrating things about Drake. Let’s talk about all of those instead.