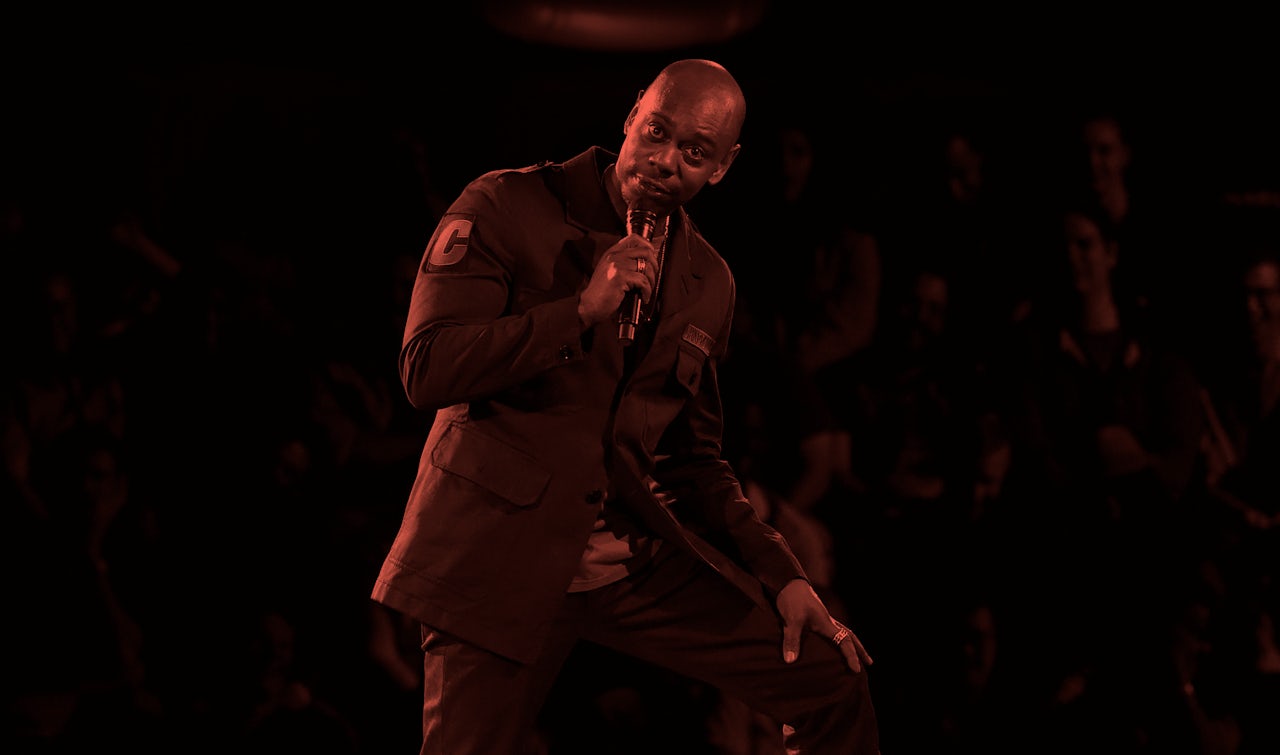

“Name-calling does not break the modern black man,” says Dave Chappelle, almost halfway into the second of two hour-long comedy specials released exclusively through Netflix last week. The bit continues with Chappelle painting a hypothetical in which his white girlfriend is on her knees giving him a handjob (“I love a good handjob!”). The hypothetical white girlfriend instructs him to come on her face… “nigger.” Chappelle tells the crowd sheepishly, “Ladies and gentlemen, I’m busting that nut in her face. I’ll sort the ethics later.”

Coming first and worrying about the ethics later makes a good metaphor for The Age of Spin and Deep in the Heart of Texas, Chappelle’s first specials in over a decade and two-thirds of a recent deal with Netflix.

I have a soft spot for comedy specials. Growing up with a parent who loved herself some Kings of Comedy (and to this day laughs as hard at every joke as if it were the first time), stand-up specials by black comedians can feel nostalgic. Until relatively recently, for me, the acronym “HBO” primarily conjured up Chris Rock in slick pleather yelling about niggas and bullet control. The bald man from Family Feud preaching to women about how to keep a man is unfamiliar to me, but I know Steve Harvey in a yellow XXXL suit and church shoes like I know a Spice Girls song.

Rewatching such specials nowadays, most around two decades old, much of the material still lands just right. Cedric the Entertainer pantomiming his way through a bit about white people infatuated with the idea of moving to space and leaving black folks down on Earth resonates in an age of Passengers and Elon Musk. Paul Mooney’s crotchety slave humor remains edgy and uproarious. “I read the white book,” he says in 2002’s Analyzing White America, “Gettin’ away wasn’t a chapter.”

Chappelle is well aware that his comedy won’t be taken kindly in the world into which he re-emerged, where language means everything.

Not everything ages so well. Chris Rock’s infamous “Niggas vs. Black People,” immortalized in the 1996 special Bring the Pain, is often interpreted as being enmeshed in respectability politics. The implication bothered Rock enough to retire it entirely. “I’ve never done that joke again, ever, and I probably never will,” he said in a 2005 60 Minutes interview. “‘Cause some people that were racist thought they had license to say ‘nigger’. So, I’m done with that routine.” But his uneasiness didn’t do much to stem the bit’s afterlife. On the first season of the U.S. adaption of The Office, the catalyst for a staff racial sensitivity training is Michael Scott’s imitation of the routine. In a campaign speech on Father’s Day in 2008, Barack Obama quoted from the joke to caution fathers against doing the bare minimum, or as Rock puts it, “some shit they supposed to do.”

This is the crux and the challenge of the comedy special: The vast majority of performances in a comic’s career will not be recorded, or even be remembered clearly outside the word-of-mouth evaluation that “she was funny as hell,” or “wow, he sucks.” Comics know this. In the live moment, they are able to make all kinds of microadjustments, even subconsciously, to attune themselves to the specific audience at hand. Comics don’t need to be timeless, only timely. No two sets look alike: Sometimes it all works out and sometimes you bomb. The camera changes everything, so recording a special requires comics to think about time in a whole new way.

Dave Chappelle is certainly aware of this. The mastermind behind (and at the forefront of) a gem like Chappelle's Show must know, and constantly reckon with, the afterlife of his own comedy. Twelve years later, we are still laughing. I do not believe art needs to be timeless to be important; timelessness is too frequently used as an impossible standard lorded over comics who incorporate overt racial themes into their work, as if an acknowledgment of the social will render a piece frozen in time. Chappelle's Show isn’t timeless because it refuses its present. On the contrary, it remains relevant because it refracts its current moment with a finesse that predicts its own cultural afterlife.

We won’t be saying the same about these latest specials in 2032, if we still have a planet by then. The Age of Spin and Deep in the Heart of Texas are timely — indeed, too much so. They are precisely indexical of today without offering a reprieve from the regular. The only acceptable future I can imagine for them is one in which they age absolutely terribly.

Chappelle is well aware that his comedy won’t be taken kindly in the world into which he re-emerged, where language means everything. In Age of Spin, he attempts to a stage an atmosphere in which he is knowingly out of touch and only halfway apologizing for it. (Perhaps this is why Netflix chose it to be the first "episode," though it was more recently recorded). “I’m 42,” he says, before deadnaming Caitlyn Jenner in order to set up a stale game of oppression Olympics between (white) trans women and black (cis) men. It’s a repeated trope in both specials. He acknowledges the perks of his fame (“I’m black, but I’m also Dave Chappelle,” he says early in Age of Spin, in a bit in which he narrates the story of a friend’s arrest) and suggests that he’s jaded by the game of “who has suffered more” (“You was in on the heist, you just don’t like your cut,” is his reply to a white woman who tries to equate her oppression with his). And yet Chappelle finds himself embattled with other subject positions, convinced black men have it the hardest and conveniently forgetting the existence of black women, black gay men, black trans women, and black lesbians, until they’re needed in service of a punch line.

Both specials lay a trap for the sort of millennial sensibility that gives Age of Spin its name, and where “everybody's mad about something,” as he says in Heart of Texas. Dave Chappelle is a 40-something who remembers watching the Challenger explosion on a television set wheeled into the classroom. In his world, trans women and gay men are akin to smartphones and the 24-hour news cycle: technological inventions he just can’t keep up with. It’s a very convenient, if not particularly innovative or convincing, gimmick.

As critics have carefully pointed out, the performances are “old”: Age of Spin was filmed in L.A. at the Hollywood Palladium in March 2016 and Heart of Texas even earlier, at Austin City Limits in April 2015. Some have attributed the comic lag that overwhelms the experience to that belatedness. Jason Zinoman at the New York Times and Caroline Framke at Vox note the absence of what Framke calls “the political elephant in the room.”

Yet it is pure laziness to blame the awkward sense of timing on a failure on Netflix’s part, as if, had they only purchased and released the specials a year or so earlier, Chappelle’s comedy would have been right on time. It’s even lazier to fall in line with the comic’s own performative assertions about generational differences to explain the –isms that appear, nearly uninterrupted, across the two hours of material.

In his world, trans women and gay men are akin to smartphones and the 24-hour news cycle: technological inventions he just can’t keep up with.

While the specials assume they will be understood as being old school, they are ultimately too timely to be shocking. As reviews roll in with words like “raunchy” and “unflinching,” it’s worth asking: How is a grown black man whose bits rely on homophobia, transphobia, and misogynoir “edgy” in 2017? I believe stand-up comedy is a great way to get difficult topics into the room. (See Wanda Sykes for a lesson on how rape jokes are done.) For comedy to be edgy it needs… an edge. But here, Chappelle lacks edge. Instead of utilizing comedy to say something truly provocative, he reproduces public opinion so exactly as to be completely boring.

I felt a nagging déjà vu when, by the end of Age of Spin, Chappelle turns Bill Cosby into a mythical hero who “saves more than he rapes.” Is this not merely a reenactment of the defenses put forth by people who wish to hold Cosby near and dear despite his crimes? From a comic whose relationship to Cosby’s memory is likely different from that of the average Cosby Show fan, working that complexity out onstage might’ve made for a powerful moment. I would have loved to see Chappelle turn the discourse on its head (a riff on the “he was trying to buy NBC” rationale for Cosby’s innocence could’ve been gold), but what we got feels like more of the same.

But it wasn’t all bad all the time. It’s hard to be mad at a decent diarrhea joke. And glimpses of Chappelle’s trademark wacky storytelling were fun to see. He segments Age of Spin with stories of chance encounters with O.J. Simpson in a comic maneuver that feels very Chappelle; after all, his tales of the rich and famous have always been something of an oddity. Similarly, moments when Chappelle summons peers such as Chris Rock and Chris Tucker feel like access into cool, unfamiliar territory. The opening sequence, narrated by Morgan Freeman with visuals by Elastic, is, in a word, sublime.

Few jokes hit a sweet spot from start to finish. He acknowledges the plight of non-black Muslims (“We all go through something, but at least I can leave my backpack someplace”) but finishes the bit with a stereotype; the uproarious laughter from a fairly white crowd is uncomfortable to watch, especially given Chappelle’s own reasoning for having left Chappelle's Show. I cracked up at idea of Nike cutting Martin Luther King, Jr. a sneaker deal, and then pulling it due his being too radical (“Really, it’s a walking shoe and we like the marching, but ehhh...”), but wish it hadn’t been used merely to defend a homophobic person’s right to retain a lucrative contract. At one point, he narrates an incident in which he and his sister are targets of a hate crime, leaving Chappelle to decide whether to press charges that could lead to jail time for the young white perpetrator. To resolve the ethical knot, Chappelle goes with the easy option: offering to drop the charges if the man’s mother will give him head.

As a Dave Chappelle fan, that is what’s most disappointing about these two specials. For a comic known for struggling with the most difficult, deliciously cringe-y parts of a joke, it’s unfortunate to see Chappelle take the path of least resistance, which in this case is also the least funny. Chappelle clearly enjoyed himself, leaving us to sort out the ethics. My hope is that the next special, due out later this year and filmed during Trump’s ascent, shows a Chappelle willing to put in some work for a more satisfying finish, for all of us.