There is a lingering resilience to Frank Ocean’s second album, Endless. Released last fall in a maneuver allowing Ocean to leave his label, the project was billed as a “visual album,” accompanied by a black and white film of Frank building a spiral staircase — a cryptic menagerie of some of the singer’s more artistically zealous tendencies. The album’s tracks, meanwhile, exist like fragments of recounted dreams. Snippets of fully realized songs jut out like samples you’ve heard but can’t place. There are only four tracks that clock in at over three minutes, and most are just over sixty seconds. But the album doesn’t feel incomplete. Instead of making you want more, the brevity of Endless inspires repeat listens.

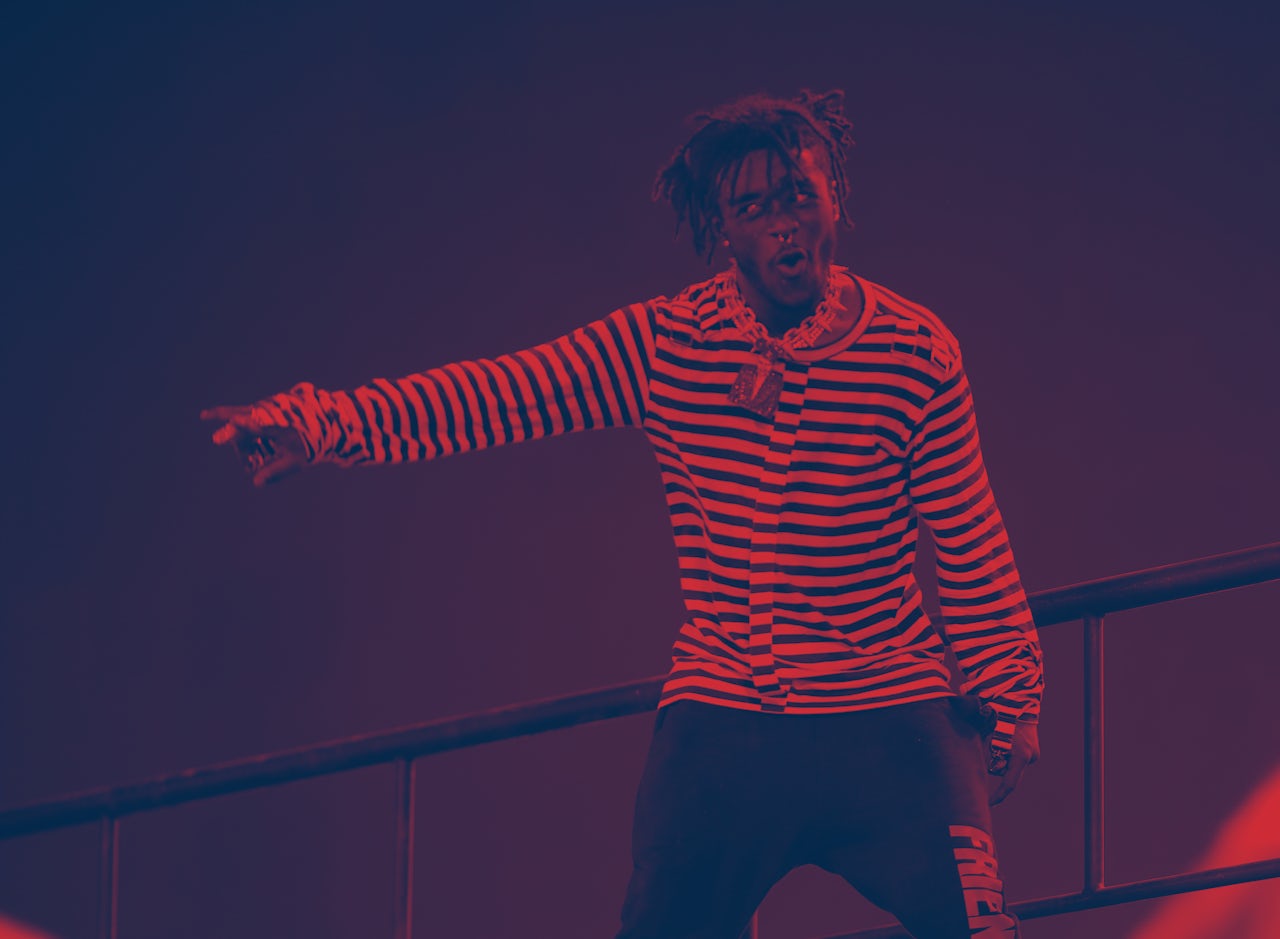

Frank Ocean isn’t the only artist finding the conventional three minute song structure increasingly superfluous. With traditional radio being replaced by online streaming as the dominant source of music, new artists are discovering that many of the old rules don’t apply. Take the 22-year-old rapper Lil Uzi Vert, whose buzzing single ‘XO Tour Lif3’ sits just under three minutes (A remastered cut puts the track at 3:01). The Philadelphia rapper’s two breakout tracks, last year’s ‘You Was Right’ and ‘Do What I Want,’ clock in well under the three minute mark, and owe much of their success to memes.

The social feeds and apps where new music is shared has introduced a novel understanding of song structure. Vine, the now deceased social network famous for rhythmic, melodic loops, has been responsible for breaking some of the past year’s biggest songs, like Silento’s 'Watch Me (Whip),' or Lil Yachty’s 'Minnesota.' Songs that grew popular on the platform had just seven seconds to catch an audience’s attention. The result was a spree of hook-driven, melodic hits from the likes Lil Uzi Vert and Lil Yachty, two artists with a penchant for punchy, readily looped tracks. Many of today’s biggest hip-hop songs have this earworm quality. Technology has maximized songwriters’ efficiency.

As the tools for producing and sharing music become increasingly universal, a new dynamic towards even shorter songs has emerged.

This is a far cry from the early days of pop music, when there were more specific guidelines about how an artist’s songs needed to be packaged to get radio play. With the advent of the 45" vinyl, for example, artists had to make sure their most popular songs could be cut to three minutes, the length the format supported. That dynamic fundamentally shaped how American pop music functioned; artists from Elvis to The Beatles defined the country’s culture while adhering to the standard. As technology expanded modes of distribution, many artists experimented with longer songs. Data from musicbrainz.org suggests that in the decades following the introduction of the 45" in the 1950’s, the average length of popular songs increased, from under three minutes to an average of around four by the mid 2000s.

Now, as the tools for producing and sharing music become increasingly universal, a new dynamic towards even shorter songs has emerged. Playboi Carti, the Atlanta rapper responsible for the soon to be ubiquitous single, 'Magnolia,' recently released a mixtape of tracks that mostly sit at roughly two and a half minutes. Many of rap’s young upstarts gain fame for self-produced tracks that, perhaps thanks to the rudimentary nature of their production, tend to rely on sparse arrangements. Ugly God, a rapper from Houston who is quickly becoming one of the genre’s most eccentric young voices, amasses millions of plays on Soundcloud with his two-minute absurdist flows.

These short singles have the same quick-hitting energy as early punk rock, a genre defined by fast, brash songs that in some cases lasted only a few seconds.

“Punk music was built on the back of three chords and two-minutes songs and minimal guitar solos,” said David Ensminger, an English and humanities professor at Lee College, and the author of Visual Vitriol: The Street Art and Subcultures of the Punk and Hardcore Generation, in an email to The Outline. “Part of that being a reaction to the ‘bloated’ FM dinosaur and prog rock and heavy metal format, but also harkening back to the golden age of rock'n'roll.”

Ensminger says that personalized playlists from services like Spotify and Apple Music, as well as the resurgence of mixtape culture, bear similarities to an even older music format: the jukebox. “The curated Daily Mix of the likes of Spotify, and the changing role of listeners from being passive to active, suggest a personalized jukebox effect to me, hence a return to short, sharp, potent tunes, just like that format determined.”

The ways that fans listen to music, naturally, have an effect on how artists construct it. It is still relatively early in the era of online streaming to determine just how different our listening habits will become. But artists like Frank Ocean and the young crop of up-and-comers finding fame on Soundcloud are experimenting in ways that remain exciting for fans, no matter how brief.