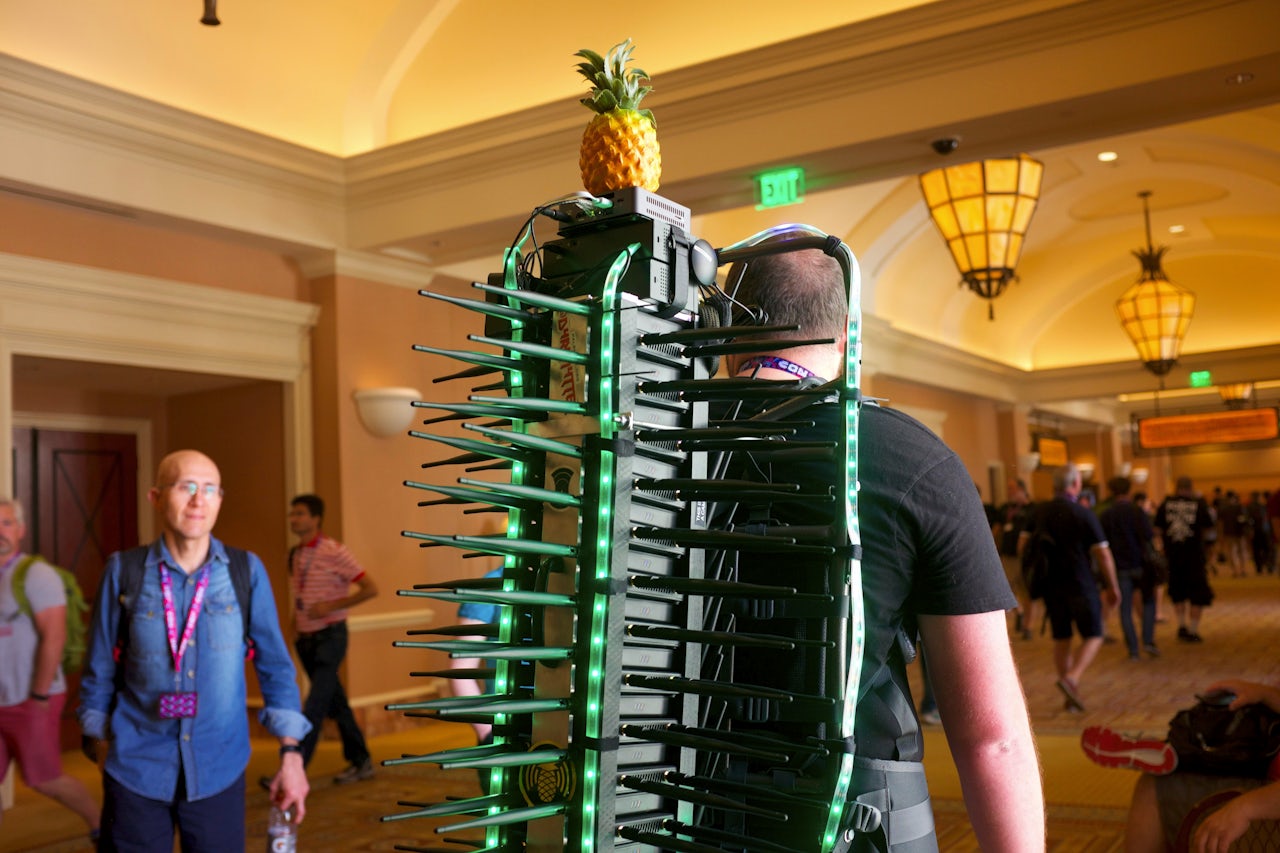

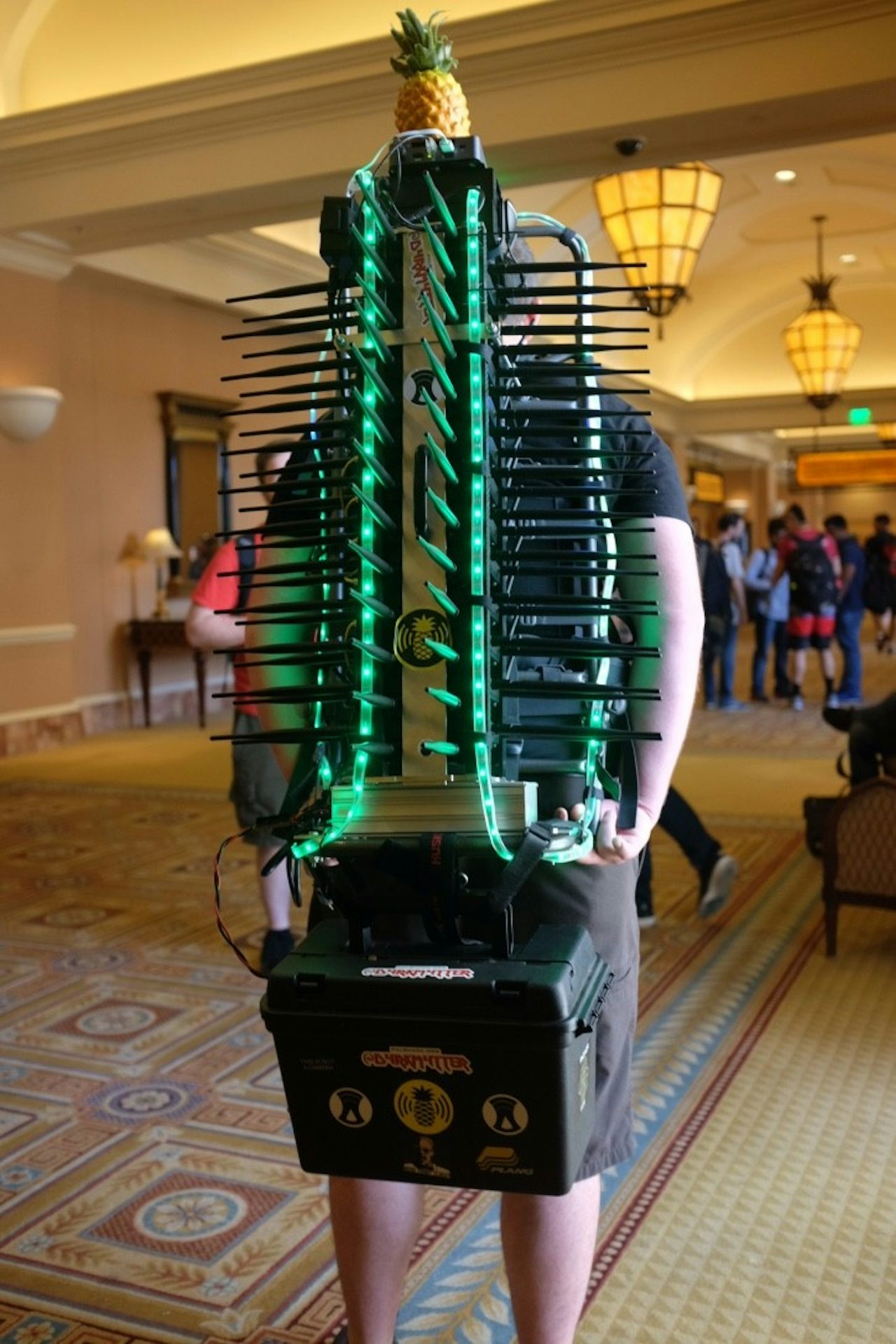

Mike Spicer, an independent security researcher who goes by the handle d4rkm4tter, couldn’t walk five feet at the Las Vegas hacker convention DEF CON last weekend without being stopped by people gawking and asking questions. That’s because he was wearing a 30-lb. backpack made of a stack of 50 radios and decorated with blue and green LED lights. “Hashtag #wificactus,” he told people as he walked through Caesar’s Palace, where the convention was held. “Get it trending.”

The Wi-Fi cactus, an intimidating piece of gear named for its spiky antennae, was a passive listening device that monitored what networks were available, and who was connecting to whom over Wi-Fi and how. Spicer called it “warwalking,” a variation on “wardriving,” which refers to driving around with a device that sniffs out open Wi-Fi networks. Back when most Wi-Fi networks were not password-protected, hackers would seek out random networks to get free internet and do things that might get them in trouble at home.

Many people are vaguely aware that it’s a bad idea to connect to a strange Wi-Fi network. But the understanding of what sort of hacking can be done through such connections, and how commonplace that might be, is lacking. During DEF CON, Las Vegas is supposedly the most dangerous place in the country to connect to Wi-Fi. The standard advice for anyone attending? Don’t do it.

Spicer wanted to find out how many people were actually getting attacked over Wi-Fi at DEF CON, and how. To do that he built a setup so powerful it couldn’t be ignored. He talked to Hak5, a company that makes a popular Wi-Fi monitoring device called the Pineapple Tetra, and the company sent him 40 Pineapples in the mail. He ended up using 25, two radios on each, to cover all the activity on every Wi-Fi channel at DEF CON.

Spicer mounted his Frankensteined creation on a backpacking frame, and schlepped around the convention. The Wi-Fi cactus has a range of about 100 meters and a battery life of about two hours. It was monitoring 14,000 devices at its peak, Spicer said, at which point his system crashed.

Spicer has not fully analyzed the data yet, but he saw a lot of suspicious activity in real time. One of the most common was an impersonation attack, he said, in which a hacker pretends to be one of your phone’s trusted networks.

Let’s say you have a Wi-Fi network at home called Katz Korner. You travel to Las Vegas for a convention, and as you’re walking around Caesar’s Palace, Katz Korner pops up. Your phone, which remembers Katz Korner as a trusted network, immediately connects to it — even though you’re miles away from home. Spicer said a popular network to impersonate is Gogo Inflight, the airplane Wi-Fi that many people have connected to at some time or another.

Spicer also saw deauthentication attacks, in which a hacker tricks your phone or laptop into disengaging from the network it’s connected to and migrating to theirs. He also configured the Pineapples to look for attacks using Broadpwn, a bug in a common phone chip that was patched and publicized just days before the convention. If not patched, Broadpwn allows a hacker to infect a victim’s phone over Wi-Fi and then use their phone to infect others.

So what type of information could a hacker get through a Wi-Fi attack? “If you connect to someone’s access point, they are essentially your internet provider," Spicer said. "They have access to the same layers of information.”

Depending on the level of security of the sites you’re visiting, hackers might be able to tell what sites you’re on and even see the usernames and passwords you type. The hacker will also almost certainly know what type of activity you are doing, the size of the data you’re transferring, and at what times.

Spicer plans to publish a deeper analysis of his observations, and he’s hoping to give a talk about it at the Utah security convention Saintcon.

“I think people should be pretty worried about it,” he said. “There is hardware that you can buy for a few hundred bucks and set up to do it. It’s cheap, it’s accessible, and the tools make it very easy to exploit these types of attacks.”

There is good news: Wi-Fi attacks are getting harder to pull off. That’s because of improved security by internet providers and websites, as well as greater public awareness.

“Luckily," Spicer said, "we are moving more and more towards a security and privacy culture every day."