If you are ever captured in the jungle by a group of men and women who taunt you, insisting they will soon devour your flesh, there are a few tricks you can use to avoid this fate. First, you can pretend to be French. It will probably help if you wail in agony, like a baby, leading them to wonder if it might be better not to consume your pathetic body. A horrible sickness may lead them to the same conclusion, and if you can stop eating for long enough to get skinny, they may likewise lose their appetite. Use this extra time to try to pretend that your God is angry and causing them misfortune, and that maybe you can cure diseases with your own powers. Most importantly, lie, lie, lie, and lie, all while learning the local language and customs, trying to make a deal with whomever you can.

This, at least, is one lesson you can draw from Hans Staden's True Story and Description of a Country of Wild, Naked, Grim, Man-eating People in the New World, America (1557, Andreas Kolbe Publishing, with woodcuts), one of the foundational texts of South American identity.

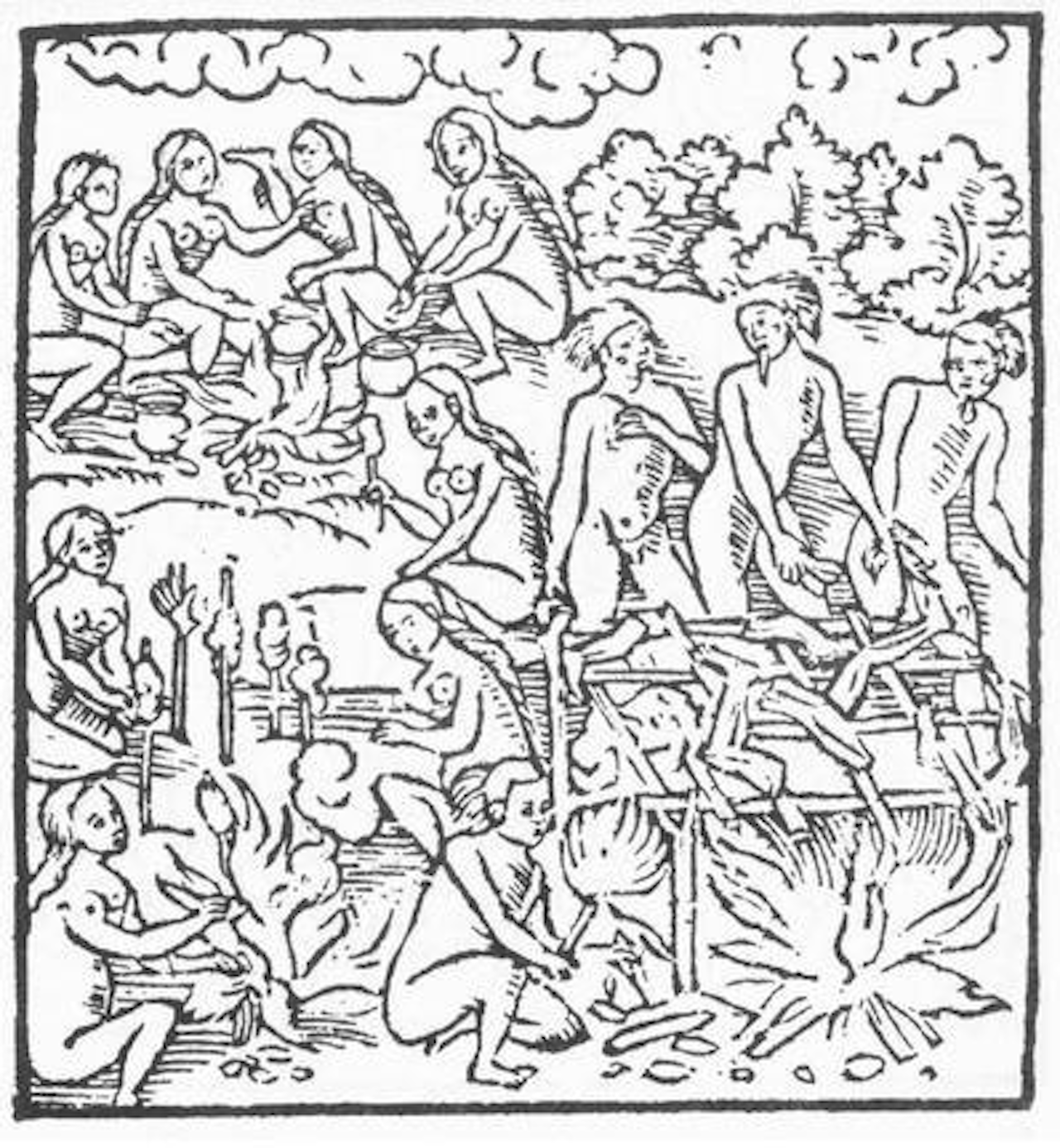

According to the book, Staden, a German soldier, was captured by members of the Tupinambá tribe in what is now Brazil, and lived with them for years, wily putting all of these tactics to use, before managing to wrangle an escape route back to Europe, where he landed a book deal. He describes in brutal detail the ritualistic executions of indigenous peoples and white Christians alike, and the magical ceremonies in which their flesh was torn apart and devoured by drunken natives. One old woman sucks raw brains out of a man's skull, just moments after he is killed. Staden, our hero, makes complicated alliances and double-crosses his allies, assumes false identities and then discards them, and concocts elaborate performances to trick the chief who owns him. It's a riveting tale.

Staden describes in brutal detail the ritualistic executions of indigenous peoples and white Christians alike

But the thing is, as far as we know, this is actually what happened. At the very least, experts have no reason to doubt the account, and as for his descriptions of the Tupinambá's practice of cannibalism, they may be some of the best we have. Some Brazilians are now proud, in a way, of this legacy of man-eating. Hans Staden was real, and he shaped perceptions of the Americas and the way other European explorers viewed their future missions.

The rest, of course, is history. Brazil is called Brazil now. It has a European legal system and speaks a European language. The few indigenous people that remain live in poverty, often still in violent conflict over land rights. Which means, if you are an indigenous Brazilian, you might draw a very different lesson from the True Story. If you capture an enemy, and he keeps making excuses why you shouldn't eat him, don't listen to his shit.

On his most famous journey, Hans Staden sailed for America in 1549 on a boat controlled by the Portuguese crown. At the time, the Portuguese were in an alliance with the Tupiniquim, another Tupi-speaking indigenous tribe living in the region, who were in a state of permanent war with the Tupiminbá, who were allied with the French.

Not much of this mattered to Staden at first, as he sailed up and down the coast. But then, they were shipwrecked. Things went from bad to worse when he was captured by the Tupinimbá, who (mostly correctly) surmised that he was on the Portuguese side in this war, and therefore an enemy. It is at this point that we all hear about a very special type of party that the Tupinimbá are in the habit of throwing.

In the month of November, when a certain fruit ripens, which they call Abbati in their language [Abati]. They make a drink out of it called Kaa. Why. [Cauim]...The Abati is ripe when they return from war. Then they have Abatis to produce their drink. If they have captured some of their enemies, they eat them together with this drink. All year long, they look forward to the beginning of the Abati-season.

Sounds extremely badass. But soon, things take a dark turn for our narrator.

They stood around me and threatened me, saying that they would eat me. Being so full and despair, I considered matters to which I had never given a thought before, namely, the vale of tears in which we lead our lives. Then I began to sing, with tearful eyes from the bottom of my heart, the Psalm [130]: Out of the depths I cry to you, O LORD. Then the savages said: Look how he cries, now he is moaning.

We will only find this out later, but the fact that he cries out is crucial. This is not how this is supposed to go. As Staden's own account makes clear, the Tupinimbá do not just eat anyone. They don't eat human flesh as a form of sustenance. They do not just wolf down any outsider. The practice is reserved for enemies, for members of groups that have been at war with them, who have killed their family members, or would kill their family members if they had the chance. Inasmuch as we can try to reconstruct any, their cannibalism has three purposes. First and second, it is revenge and a warning. In this way, it serves the same societal function that Europe's elaborate torture-executions — as the essays in this edition (highly recommended) note, these were ongoing at the time of Staden's writing and often much more cruel than the simple club to the head that Tupinambá food received in its final moment of life.

Third, the ritual is sacramental. The community ingests not only meat but some of the power and identity of the vanquished. The individual in charge of the ceremony even takes on a new name after the dinner is over. He has incorporated a new person into himself.

In some ways the feast might bear some similarities to the the Catholic Eucharist. This was what at least some of Staden's fellow Protestant faithful were soon arguing — informed partially by accounts of “cannibalism” from the Americas — about the Church of Rome.

When the Tupinambá eat the wrong person, or eat the wrong way, they know there are consequences. Staden has one long conversation with a chief who became sick, fevered and hallucinatory after one meal he particularly regrets. In another case, the locals recognize a captured enemy is diseased, so they eat him strategically, casting aside the head and the intestines, to as to only take in what is good and pure.

If you capture an enemy, and he keeps making excuses why you shouldn’t eat him, don’t listen to his shit.

But Staden is different. Instead of bravely accepting his fate like others in Brazil often did, loudly declaring his power and his hatred for the Tupinimbá, he desperately pleads that he is French and not actually an enemy. It is not clear what actually saves him. It could partially be timing, as he was not fattened, foreign and fully hated at a convenient time. At one important moment, he comes down with a horrible toothache, therefore preventing villagers from overfeeding him to beef him up. It could be that he learns Tupí well enough to participate in the interpretation of dreams and caring for the sick, inserting himself into their symbolic economy as something much more than an aggressive outsider.

Or perhaps, they came to the same conclusions that the reader might while going through Staden’s account. That he is a kind of a whiny baby, usually seeming more pathetic than appetizing, and also that he is a naive but clever unknown quantity. That he is perhaps innocent, or at least that he truly believes that he is innocent, and that he is no true enemy to his captors. Despite all his other lies, he really does believe this, and this belief might have been convincing.

Remarkably, Staden’s life continues even after the tribe comes in contact with an actual Frenchman, who proves to be much more willing to sacrifice the soldier for absolutely no reason than the natives themselves are. The exchange is illuminating.

He addressed me in French, and I could not understand him. The savages stood around and listened to us. Then, as I could not answer him, he spoke to the savages in their own language: Kill and eat him, the good-for-nothing. He is a real Portuguese, your enemy and mine.

Staden then turns around to his captors and insists, incredibly, that he has actually simply been away from Europe so long that he has forgotten his own language. It's not really clear why the Tupinimbá swallow that one, instead of him.

Eventually, through more trickery, Staden wins over the local French as well, and wins his freedom. He becomes a minor celebrity in Europe, and makes his publisher a good deal of money. Instead of entering the bodies of Americans, Staden takes their rituals back to Germany and their story enters European consciousness, as that continent ingested stories of savages and converted them into fuel for the four centuries of colonialism that would follow.

A lot happened between 1557 and 1928, when the modernist poet Oswald de Andrade published the Manifesto Antropófago, another foundational text of South American identity. More than half of the continent Staden originally visited passed completely into Portuguese control, and became a nation-state, with European laws and a white European elite. The indigenous peoples either were absorbed into that new body politic or remained on its margins. Western Europe itself went from being an outpost of backwards, dirty, fundamentalist idiots — rightly ridiculed by more progressive and intellectual Arab and Chinese civilizations — to the rulers of empires across the globe, and then began the process of destroying that very system by attacking each other in 1914. A large settler colony in North America, speaking a different Western European language, began to move into a position that could rival or even surpass the Europeans, leaving the Iberian-speaking settler colonies to their South far behind, in the “developing” world.

Radical modernism came into vogue, and so did bold manifestos. The Futurists and the Surrealists had theirs, of course, and young “Brazilians” found themselves as post-colonial subjects. Communism had arrived on the Earth's surface, and Primitivism was also big, especially in European intellectual circles.

It's in this context that Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade wrote the “Man-eater Manifesto,” drawing upon Staden's story, and Brazil's now well-known history of cannibalism, to re-affirm the practice of wolfing down foreigners as a noble, even fundamental, and revolutionary act. De Andrade and the rest of the world only knew about Brazilian cannibalism through texts produced by the European outsiders themselves, as the Tupí-speaking peoples did not write their own histories, and the voice they did have to do so was cast aside as Brazil was created.

The anthropófagia he put forward was of a specific type. He — like Staden's captors — was not defending the consumption of everyone by anyone, but of a specific ritual, with a specific target. Some feasts are glorious and value life, while others are criminal, or will cause madness. The conquered should eat the conqueror, only ingesting the best bits and using them to fortify her strength. The poor should eat the rich, avoiding any parts of the body which might be infected and taking the nutrients that can be useful for building a new, stronger body.

The text is difficult, even in English translation, but here's some of its most memorable lines.

We had justice codified as vengeance. Science codified as Magic. Anthropófagia. The permanent transformation of Taboo into totem.

It was not crusaders that came here. They were fugitives from a culture that we are eating, because we are strong and vengeful like the Jabutí.

But he delivers its most forceful line, or at least the phrase that was digested into Brazil's corpus most famously, in English:

Tupí or not Tupi, that is the question.

For the proud anthrophage, there is nothing more natural than to devour the language of Shakespeare, digest it, and use it for his own purposes, in an anti-colonial polemic text.

This is why it was so profoundly, amazingly stupid for a New York Times opinion writer to recently imply that the words of Martin Luther King could be cultural appropriation. “The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered some of the most sublime speeches of the 20th century. In them he used a mostly Latinate language to evoke the trials of the Israelites while quoting the writings of a slave-owning founding father,” wrote Bari Weiss, probably trolling. If Weiss was not trolling, she was making an appalling mistake, confusing good cultural cannibalism with the bad. For a civil rights leader, fully devouring and appropriating the language and tools of the culture that oppress him is a heroic, self-fulfilling act.

Tupí or not Tupi, that is the question.

Cultural appropriation is something else entirely. Cultural appropriation is when you are standing on someone's neck and you try on their hairstyle for fun, profit, or both. Copying the hairstyle isn't the real crime. The real crime is where you are standing. It doesn't matter if you don't know you are standing there, if you were born standing there and perhaps would prefer not to be standing there if you had a choice, or if you really do like the hairstyle.

The thing to do is get off. And if you cannot get off — and often, for structural or political reasons, this can't be done easily, or right away — you should at least be trying, and the very very least you can do is acknowledge where you are, and to realize that while standing up there, trying out some of the culture from below is to add insult to injury. Sometimes the insult is to the cultural symbol itself, which is rendered banal or ridiculous. Or often, the appropriation serves to force the impression that two people are on equal footing, when in reality one is exploiting the other.

Bad cannibalism — cultural appropriation in the offensive sense — can only really be practiced by specific subjects in a specific contexts. The vast majority of the human population, living far from positions of obvious power and privilege that could make free exchange with other cultures a sham, need not worry too much about their guilt.

Cultural appropriation is when you are standing on someone's neck and you try on their hairstyle for fun, profit, or both.

It doesn't even matter if your appropriating heart is pure. All the evidence we have indicates that Staden bore no personal ill will towards the native people of Brazil when he arrived. But it is undeniably, obviously, stupidly clear that he ended up playing a large part in a process that entirely destroyed indigenous life on its own continent. In modern American culture, we have such a liberal, individualistic notion of morality and punishment that cultural appropriation barely fits — and really, maybe for now the term has been ruined by its misapplication and we'll even have to start over — because we can't conceive of structural injustices and a crime without the intent to do personal harm.

This liberal structure is mostly good, but it would have done nothing for Tupi-speaking peoples trying to defend their homeland, and it stops us from differentiating appropriation from antropófagia. Cultural appropriation doesn't even have the savvy to fully process or understand what it steals, while the anthropophage eats when it is right, and eats fully and wisely, and becomes something larger.

In the 1960s, there was a cultural debate between some left-wing Brazilians, who thought foreign pop culture should be rejected in its entirely as imperialist, and the Tropicalistas, who loudly declared their allegiance to de Andrade and Antropófagia, saying that they'd cannibalize music from the US and elsewhere for their own purposes. The result was so revolutionary that Brazil's U.S.-backed dictatorship forced artists into exile, while they continued to produce music much better than your culture ever could.