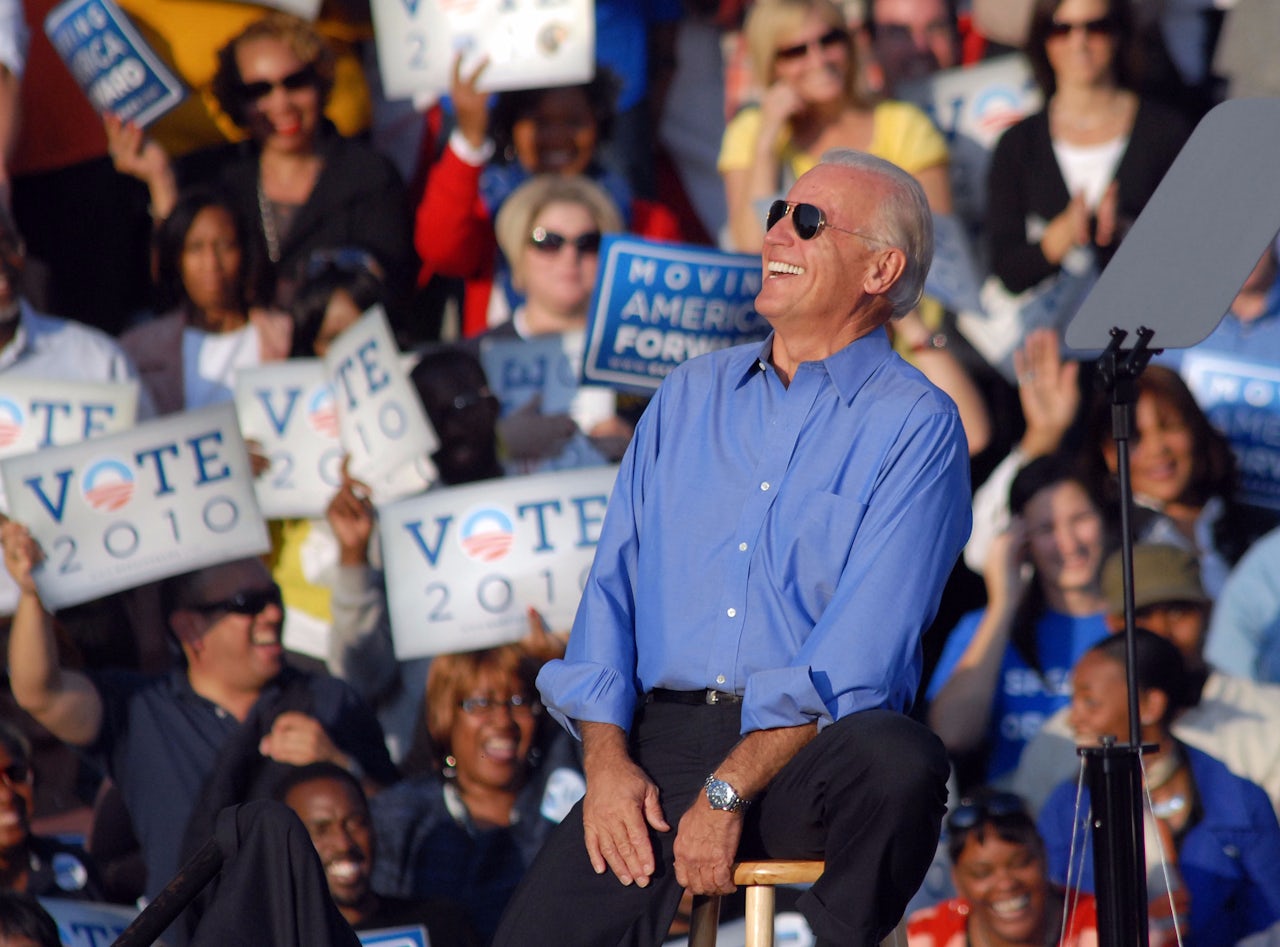

At a time when Democrats finally have a reason to be (tentatively) excited about the future, Joe Biden’s stock is thriving, with a new book, praise from prominent Democrats and Republicans, and polls showing him with a double-digit lead in a potential match-up with President Donald Trump. But Joe Biden can’t save the Democrats and, more importantly, we musn’t overlook his political shortcomings. While the former vice president can certainly rock a pair of Ray Bans, he has a dismal record on criminal justice and holding the financial elite accountable, and has a tenuous history with women. If Democrats and progressives want to challenge the strength of the Republican Party nationally, they have to look to the future, beyond the politics of the old-guard Democratic Party, where Biden happily resides.

Starting within days of Trump winning the presidency last year, Biden has been mentioned as a leading contender for 2020. A recent Public Policy Poll showed him running 18 points ahead of Trump in a hypothetical matchup. And in Democratic National Committee chair Donna Brazile’s new book about the 2016 election, she writes that she “seriously contemplated setting in motion a process” to replace Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton with Biden after Clinton fainted after a public event last September 11.

Biden has done little to dispel the notion that he might run again. In October, he told Vanity Fair that he decided that he wasn’t “going to decide not to run.” He also launched a political action committee in June called American Possibilities, which is “dedicated to electing people who believe that this country is about dreaming big, and supporting groups and causes that embody that spirit.” And last week, Biden gave a speech at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in which he referred to Trump as a “charlatan.”

Biden has said he regrets his decision not to run in the last election, which he has said was driven by the grief of losing his son, Beau, who died in 2015. But in a New York Times interview published Tuesday promoting his new memoir “Promise Me, Dad,” he talks about Beau and his other children urged him to enter the race. “Beau, Hunt and Ashley didn’t want me stepping back,” he said. “They thought that what limited talents I have that may not have been suited for winning decades earlier were exactly what the public was looking for now.”

Biden’s stock is thriving, but it shouldn’t be.

It’s fairly obvious why a third Biden candidacy — he withdrew in 1988 before the first primary after it was discovered that he plagiarized a speech from a British politician, and exited in 2008 after finishing fifth in the Iowa caucus — might be popular with a cross-section of the Democratic Party that wants a return to the Obama years and/or a return to the center on economic policy. Biden, in his humble, folksy way, has a natural ability to speak to the much sought-after “white working class,” owing to the environment he grew up in.

This is part of the reason Obama picked him as a running mate in 2008 in the first place and, unlike Trump, Biden has the backstory to substantiate his connection to the working class. Biden also boasts bipartisan support. In an interview with New York magazine this week, Ohio’s Republican governor (and former presidential candidate) John Kasich glowingly described Biden as “an old lunch-bucket Democrat… a day at the mill and a shot and a beer and we’re going to give everybody a chance.”

Although Biden would theoretically run as an extension of the Obama presidency, his political record deviates from Obama’s in several key ways. During the primary, both Clinton and Sanders were sharply criticized for their support of the 1994 “crime bill,” which contributed to mass incarceration over the last two decades; Biden not only helped to write the bill but defended it as recently as last April for, among other things, putting “100,000 cops on the streets” and “restoring American cities.” And Biden not only voted for the Iraq war, but was chair of the Senate Foreign Relations committee at the time. Biden was singled out for criticism by a UN weapons inspector, who called his hearings a “sham,” and said: “It is clear that Biden and most of the Congressional leadership have pre-ordained a conclusion that seeks to remove Saddam Hussein from power regardless of the facts.” (Giving credit where credit is due, Biden warned against the invasion of Libya.)

While both Clinton and Sanders were criticized for being tone-deaf on race last year, Biden also has a well-documented history of making racist statements, like when he said in 2007 that Obama was the “first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy." There was also that time in 2008 when he said that “you cannot go to a 7-Eleven or a Dunkin' Donuts [in Delaware] unless you have a slight Indian accent.”

Biden has a well-documented history of making racist statements and being weird with women.

Moreover, Biden’s record with women is not great. Biden played an integral role in the passage of the Violence Against Women Act (passed as part of the “crime bill��), which has contributed to a reputation “as a champion of women,” as Sen. Elizabeth Warren wrote in a 2002 article for the Harvard Women’s Law Journal. But Biden should also be remembered for how he presided, as the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, over the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in 1991. When Anita Hill, who accused Thomas of sexual harassment, was called to testify, Biden did “little to stop the attacks” on her and chose “not to call three other witnesses who would have echoed Hill's charges of sexual harassment,” Politico writes. More recently, Biden’s tendency to touch women inappropriately —long written off as part of his charm — has come into long-past-due scrutiny.

But even if you write off all of the dumb things he’s said or done as authenticity, Biden’s ability to talk to the white working class is not the only reason the center might amenable to him. Biden, a longtime senator from exceedingly corporate-friendly Delaware, has long been a fan of Wall Street and financial institutions in the way that two of his possible challengers for the Democratic nomination — Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — have not been. “Guys, the wealthy are as patriotic as the poor,” Biden recently told a crowd in Alabama while stumping for Senate candidate Doug Jones. “I know Bernie doesn’t like me saying that, but they are.”

They’ve been a fan of him as well. Biden’s largest campaign contributor over the last 21 years of his career in the Senate was the credit card issuer MBNA, a now-defunct bank based in Delaware. And while representing a state where the credit card industry is king, Biden championed a bankruptcy “reform” bill that was an “industry favorite,” according to ProPublica, and which eventually culminated in a 2005 law for which Biden voted.

Biden tried to paint the bill as good for consumers, but one study released after the bill went into effect said that it "profited credit card companies at consumers' expense." Criticizing a Biden statement that the bankruptcy bill “actually improves the situation of women in children” in the aforementioned article, Sen. Warren, then a Harvard professor, wrote: “Not a single women’s group that has spoken publicly about the bankruptcy bill agrees with him.”

If Democrats want to change their long-term fortunes, they need new candidates.

It may very well be true that Biden could be the strongest-positioned candidate to face a weak Trump in 2020. But if Democrats want to change their long-term fortunes and win back the trust of the whole working class (not just white voters who voted for Trump), they’ll need to look forward, and toward candidates who are genuinely committed to improving the situation of both the working class and the marginalized in ways that they can almost physically touch — the deep relief that comes from not worrying about going bankrupt due to a medical emergency or not being able to paying your bills because you don’t make a living wage.

Peel Biden back beyond his tone and approach, and you’ll find a politician whose interests align as comfortably with Wall Street’s as the last Democratic nominee. What he fundamentally believes is that financial institutions and the people who control capital are partners with which to find a solution to our societal problems. The reality is that they are the problem. Until the Democratic Party is willing to admit this, it will continue to rely on backlash to woefully unpopular Republicans to drive support. And so these cycles will continue to repeat, and whatever incremental progress we make will constantly be under attack once Republicans take power every four to eight years.

The Democrats will always be a party of capital, and so center-left politicians like Biden –– and Ralph Northam, the governor-elect of Virginia –– will always have a home there. But in looking for leaders for a broad-based coalition against Trumpism and the GOP, Democrats will need more figures who are unafraid to fight for economic and social progress, even if it means having even a moderately adversarial relationship with the financial elite who have a firm grip on power. In other words, someone who isn’t Joe Biden.