Last January, I was broke. I lived in a car, and that month I had to choose between paying my cell phone bill or buying food. Two years before that I was a freelance photographer in Chicago, but walked away from that life to travel around the country. My travels had given me a collection of stories and photos I was proud of, and more than 9,000 people were following me on Instagram. I loved what I was doing, but I didn’t make a dime doing it. I’d hit bottom at the worst time, mid-winter, far away from my comfortable network of jobs and connections back in the city. I decided to take a shot at Patreon, a crowdfunding site that encourages artists to “regain creative freedom” by raising money directly from fans. I knew friends had made Patreon accounts over the years, selling their art and music, funding their writing and podcasts, and figured if I could make $400 to $500 a month, I could continue doing photography full time.

Patreon is basically a payments processor designed like a social network. Every creator sets up a profile where they fill out a prompt about what they’re making: “Oliver Babish is creating cooking videos,” or “Hannah Alexander is creating Art and Costume Designs inspired by pop culture and Art Nouveau.” Patreon encourages creators to provide a description of themselves and their work and strongly suggests uploading a video — “This combo is incredibly motivating for fans — it shows how real this is to you and how much you value their participation in your journey,” the site says. Next, you set up “rewards” — these are the tiers that your patrons can choose from. You can set these up so that patrons get something for their money, like an update only for patrons or some patron-only content, or you can set them up to reflect what your patrons are paying for (for example, Naomi Wu, a DIY technologist in Shenzhen, says patrons who support her at the $1 tier are paying for a bag of screws, and those who donate at the $5 tier are paying for her lunch). Then you set goals, which are actions tied to monetary benchmarks, such as being able to quit your job in order to pursue your creative passion full time.

I wrote my bio and added a short story about a sunset, a mountain, and the bandits who hid out there a century ago. I set up tiers so my Patreon subscribers could get stories published to Patreon or stories accompanied by a photo every week in an automated text, depending on how much they donated. I’d used a similar format on Instagram, where hundreds of people liked my photos and story captions, so I was eager to see who all would drop $5 to support my work. After an hour, my page was set up. I added a picture of me with my dog. My dog is very cute, so I figured I should capitalize on that. I was thrilled when 24 of my friends and family signed up to be my “patrons” and I made $120 in the first month.

When Jack Conte, a former YouTube musician, and Sam Yam, a co-founder of the mobile ad platform AdWhirl, launched Patreon in 2013, Conte posted a video he had made for an original song called “Pedals.” The video cost him $10,000 and three months to make and got nearly 2 million views, he said, but he made just $963 through YouTube’s ad network. “This devaluing of art and creators is happening at a global scale,” Conte wrote in a blog post on Patreon. “It actually makes my heart sink when I think of the magnitude of the web’s systemic abuse of creative people.”

Today, successful Patreon creators include Chapo Trap House, a lefty podcast with 19,837 patrons at the time of writing paying $88,074 a month; the news commentator and YouTuber Philip DeFranco (13,823 patrons paying an amount that is undisclosed, but is enough to put him in the top 20 creators on the site); and the gaming YouTuber Nerd³ (4,494 patrons, $8,003 per month). It’s enabled many more indie creators, including members of communities at risk of poverty such as the trans community, to support themselves and each other. Ayla Arthur, an artist and trans woman in Chicago, has been funding the comic she writes on Patreon for two years now. Arthur works in a pop-up store part time, making $15 an hour, but she spends between 20-25 hours a week updating her comic and on Patreon she currently earns $200 a month. That was enough to let her buy a tablet for illustrating. “It's a way of keeping people most at risk of unemployment afloat while they do what they love,” she told me.

But despite the revolutionary rhetoric, the success stories, and the goodwill that Patreon has generated, the numbers tell a different story.

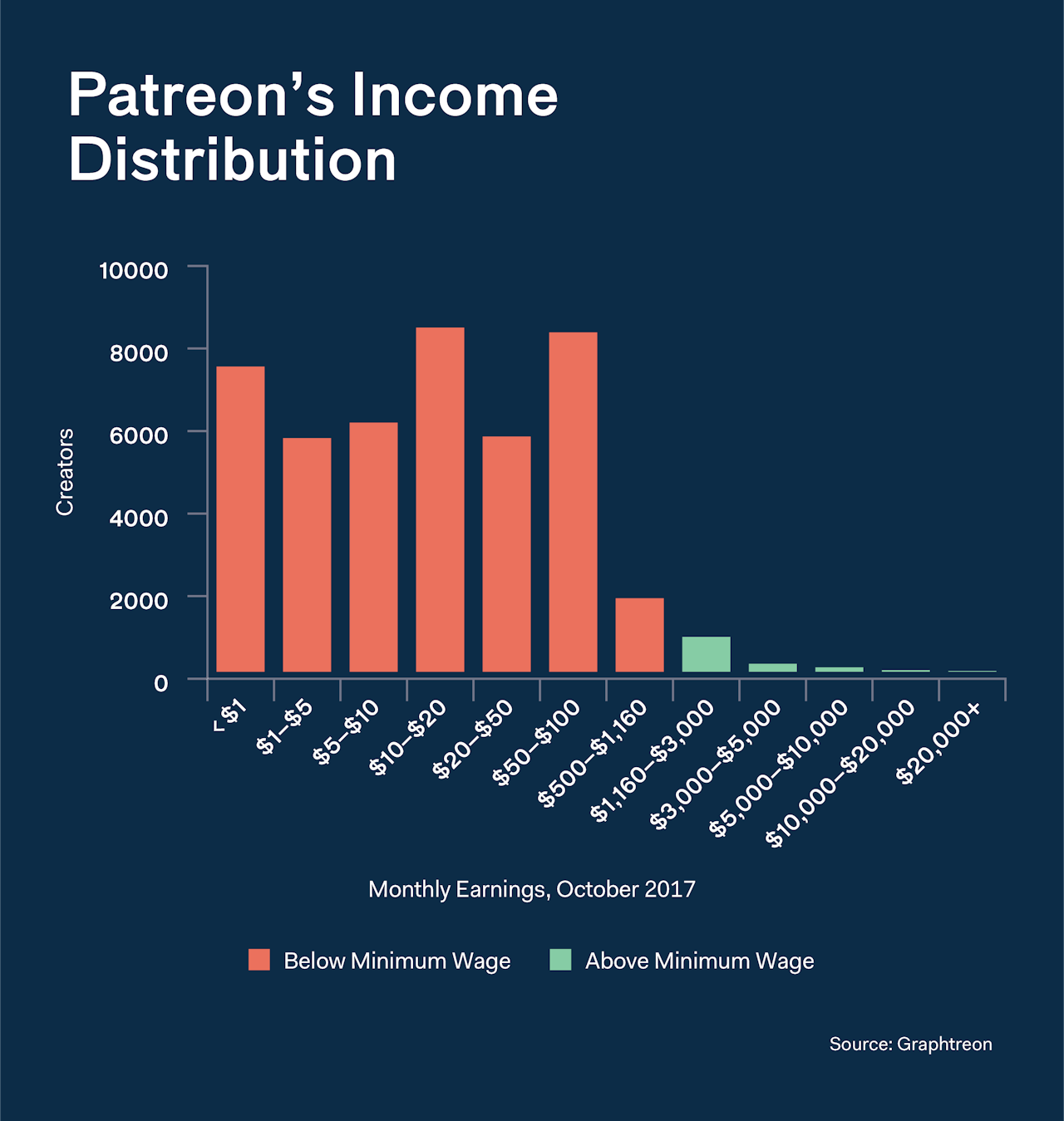

Patreon now has 79,420 creators, according to Tom Boruta, a developer who tracks Patreon statistics under the name Graphtreon. (He has his own Patreon — “Graphtreon is creating Patreon graphs, statistics, and history” — which earns more than $500 a month.) Patreon lets creators hide the amount of money they are actually making, although the number of patrons is still public. Boruta’s numbers are based on the roughly 80 percent of creators who publicly share what they earn. Of those creators, only 1,393 — 2 percent — make the equivalent of federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, or $1,160 a month, in October 2017. Worse, if we change it to $15 per hour, a minimum wage slowly being adopted by states, that’s only .8 percent of all creators. In this small network designed to save struggling creatives, the money has still concentrated at the top.

“Finally, ‘starving’ and ‘artist’ no longer need to be joined at the hip,” according to Patreon, in one of its many positive blog posts about its successful creators. But Patreon seems to know that most of its creators are actually making a pittance. In 2016, Patreon boasted that 7,960 users were now making over $100 a month, which struck me as such an insignificant monthly income to brag about. Around the same time, the company reportedly had 25,000 creators, meaning only 31 percent of Patreon’s users were making over a hundred bucks.

Traditionally, patronage depended on the benevolence of aristocrats, who would donate money to the artists whose works they enjoyed. Patronage has existed anywhere a rich, upper class controls most of the wealth and resources, from feudal Japan to Europe’s Renaissance. But while Patreon invokes figures like Shakespeare and Mozart as models for the company’s vision of patron-supported creators, those dudes weren’t raising cash from family and friends — and they weren’t having to work at Whole Foods to pay rent.

“We’re seeing new creators flock to Patreon faster than ever to create a sustainable salary for their art,” Maura Church, data science manager at Patreon, told Fast Company earlier this year. Yet none of the creators I spoke to for this story have managed to make a living exclusively on Patreon.

Patreon had all these great selling points and stats. I could get “meaningful revenue” from my fans, and finally find the “creative freedom” I’d heard so much about. Patreon’s about page said creator’s incomes “doubled annually.” Their blog has story after story after story of their users making thousands a month. Of course I was grateful for everyone who contributed to mine, but none of the site’s promises were coming true.

After launching my Patreon, I struggled for months to find work. Patreon filled my downtime, and became a full time job itself. I’d spend hours combing through photos, looking back on notes I’d taken on the road, researching where I’d been. I’d post on Twitter and Instagram with teasers, free stories, anything to attract my followers to my Patreon page. I made friends on the site, I shared their projects on my own social media, and kept up with all my subscribers’ projects. It was a lot of work for little pay, but I was determined. A year later my monthly earnings on Patreon have grown from $120 to $163.

It’s easy to feel like the failure of my Patreon is entirely on me. It’s an anxiety most artists feel acutely: Am I actually any good? This paranoia is bolstered by the presence of wildly successful creators on the site, and there is a nascent market for Patreon advice in the way that Kickstarter birthed an industry of professional crowdfunding consultants. In a post on the official Patreon blog, 30 creators shared their secrets to success. Mike McHargue, who makes $3,402 a month to make the Ask Science Mike podcast, offered this: “Stop waiting to make the perfect thing — what you can release this week will always beat what you dream of releasing next year.” Tabletop Audio, a composer and sound designer who earns $1,107 a month making ambient music to accompany tabletop games, said folks should “try to convey the pure sense of joy you get from creating. Let people know there’s always room on your team. Encourage interaction, suggestions, and feedback.” YouTuber Amanda Lee, who makes over $4,000 a month, said, “Channel your creativity into something you’re passionate about — don’t just create something to please others or to gain views.” Patreon started an invite-only annual convention last year named PatreCon. In 2016 it was held it the Patreon office in San Francisco, where 40 Patreon creators attended talks by other creators, including a keynote by Jack Conte in which he passionately advocated for “the importance of making great stuff.”

Derrick Tarrance, an illustrator and games developer in Chicago, joined Patreon in October 2016, giving patrons access to weekly illustrations, behind the scenes footage, and letting them vote on what he’d illustrate next. Patreon enforced a bad habit of “comparing your works to others and asking a million questions about how they got where they are,” he said. “Things like ‘how do they have so much time?’ or ‘how do I get exposure without DYING from working too much?’ would come to mind.” Between raising a family and having a full time job, Tarrance was discouraged by how he rushed through making art to meet the weekly deadlines of his Patreon. “It often had me stressed, instead of inspired, because I continued to feel like this isn't enough.” When he ended his Patreon in May 2017, it had nine supporters, and he made just $59 a month.

Even if creators are struggling to make money, investors see Patreon as a goldmine. In September, Patreon announced a $60 million dollar investment from venture capital firms, bringing its total funding to $107 million, according to Crunchbase, which tracks startup investment. Investors are excited about Patreon’s business model, which takes 5 percent from the money raised by creators, because subscriptions represent steady revenue, Wiredreported.

In this small network designed to save struggling creatives, the money has still concentrated at the top.

Patreon is also attracting competitors. On November 15, Kickstarter relaunched a defunct 2012 service called Drip as a separate site that allows creators to sell monthly subscriptions. Drip is invite-only for now, which at least means its more elite pool of creators — people like the feminist cultural critic Anita Sarkeesian — are making bigger sums. But even Sarkeesian is only bringing in $1,945 a month for her podcast, which is not that much money when you consider that she’s splitting it with two co-hosts.

But even those who are happy with their Patreon income are starting to feel frustrated with the difficulty of earning a living wage through the site. “Patreon is constantly selling itself as something other than [a payment processor], something much more intensive & demanding,” said Molly Lewis, a songwriter who joined Patreon in November 2013.

Lewis offers lower audio quality versions of her music to lower, cheaper tiers on her Patreon for fans who can’t spend as much on her high quality audio. Saving different file types for those lower tiers is easy enough, but once on Patreon she’s stuck having to make multiple posts, shared to multiple groups, with almost no automated help from the site. “To fulfill my Patreon rewards as a songwriter, I have to basically do that work 4 times over, for every song,” she told me. “Patreon itself is a real thorny bush I have to walk through every time I want to talk to my supporters, but it still puts us in the same yard.”

Molly attended Patreon’s convention in 2017, and has spoken directly with higher-ups at the company, asking Patreon for features to ease the work redundancies of the multiple posts and updates she makes to reach all her different patron tiers, but she says there’s been no progress for years. “I feel like Patreon keeps adding new rooms to their house without checking that the extant rooms are furnished,” she said.

While I was writing this article, Patreon made a change in how it does business. For years, creators received 90 percent of their monthly earnings: 5 percent went back to Patreon, the middle man, and the remaining 5 percent went to fees and taxes. This changed in an email sent to creators this week, announcing that creators would take home “exactly 95% of every pledge, with no additional fees.” While it seems like great news for Patreon’s creators, the response was livid. The fee change comes at a cost to the site’s patrons, and indirectly to its creators, who will get a higher percentage of donations but of a smaller dollar amount. Patreon is making up the lost 5 percent fee on creators by charging patrons an additional 2.9 percent + $.35 for each transaction. This means smaller donors will be hit the hardest. Jason Scott, who works for the Internet Archive and funds a podcast through Patreon, called the change “a skyrocketed tax on small donations (the majority).” Many creators said they would seek alternatives to Patreon. “They're trying to sell it to us as "You get a bigger % of the money!" but a bigger percentage of less money isn't a selling point,” tweeted the comic artist who goes by the handle Gibson Twist. “Also, are we not supposed to notice the huge spike in how much Patreon takes of my supporters' coin? Is this right?” “This blows and continues to convince that Patreon isn't especially interested in having a platform to help smaller, niche creators,” tweeted the illustrator and designer Erica June.

I asked Lewis how she felt about the fee change. “The per-pledge charge they're moving to uniquely puts smaller patrons at a disadvantage — and Patreon is already pretty unfair to their small Creators,” she said.

“I feel like Patreon keeps adding new rooms to their house without checking that the extant rooms are furnished.”

Indeed, the creators Patreon seems to value most are those who not only make stuff people like, but are also good at marketing their stuff and themselves. At one of Patreon’s events, Lewis told me, an executive talked about hiring practices — as in, “you’re making so much money on Patreon that you have to hire someone to maintain it,” she recalled. The executive referred to one of Patreon’s internal job listings as an example, and Lewis wrote down the job description. It said: “You can get Patreon’s foot in the door with creators [with] established followings who regularly post online. You understand our Target Creator.”

“We realize not all creators yet earn a full-time wage, but many of them do,” a Patreon spokesperson told me in an email. “We hope that as we grow, and as creators grow, that more creators can be artists full-time.”

I’m still trying to make Patreon work. My plan is to keep doing it for a month to see if it can still prove fruitful for me, but I’m doubtful. Many Patreon creators start with a $1 tip jar option, then $5 or $10 options for monthly content. I started with a handful tiers, but with each tier the work to maintain my Patreon multiplied — and now with the new fees, the $1 level doesn’t really make sense. I’m back to working as close to full-time as I can as a freelance writer and photographer, so I only spend a few hours a week writing stories for my patrons.

One thing I’ve noticed is that most of the work is done outside Patreon. I promote my page on social media and deliver it to my supporters by text message. The one thing Patreon has done well is taking my patrons’ money and putting it in my bank account, which is the very service they’ve threatened with this latest change. So, I’ve scaled down to just one, simple, $5 tier. Just in case any big spenders come across my humble page, I posted a gif of my dog and included a $69 tier to pay for his food. No one has done it yet. When I first signed up, I thought I was the perfect match for Patreon’s model. But now I’m realizing that as a struggling photographer without a massive social media following, I’m probably not Patreon’s Target Creator.

Update: This story has been updated with a statement from Patreon.