Troy Johnson started The African American Literature Book Club in 1997 and registered AALBC.com in 1998. It contains reviews of new books, lists of authors, and forums, and according to him it is “the oldest, largest, and most frequently visited website dedicated to books by or about people of African descent.” Johnson has also maintained a list of other websites dedicated to black American literature for almost as long, and over the years he has noticed a disturbing trend: while the web at large is growing, the number of websites devoted to black American books has actually been shrinking. Before 2011, there were around 67 sites. In 2011, it fell to 55. In 2015, it fell to 42. Now it’s 30.

BlackHeritageBooks.com, gone. TheBlackLibrary.com, gone. BlackBookNetwork.com, Urban Book Source, Rawsistaz, gone. Originally, Johnson restricted his list to sites with an Alexa ranking, but he dropped that requirement because the list was getting so thin.

The explanation is familiar: Google made changes to its search engine that caused the traffic to these sites to nosedive, Johnson said. One change came in 2011 with its Panda update, which was intended to decrease traffic to spam and low-quality sites.

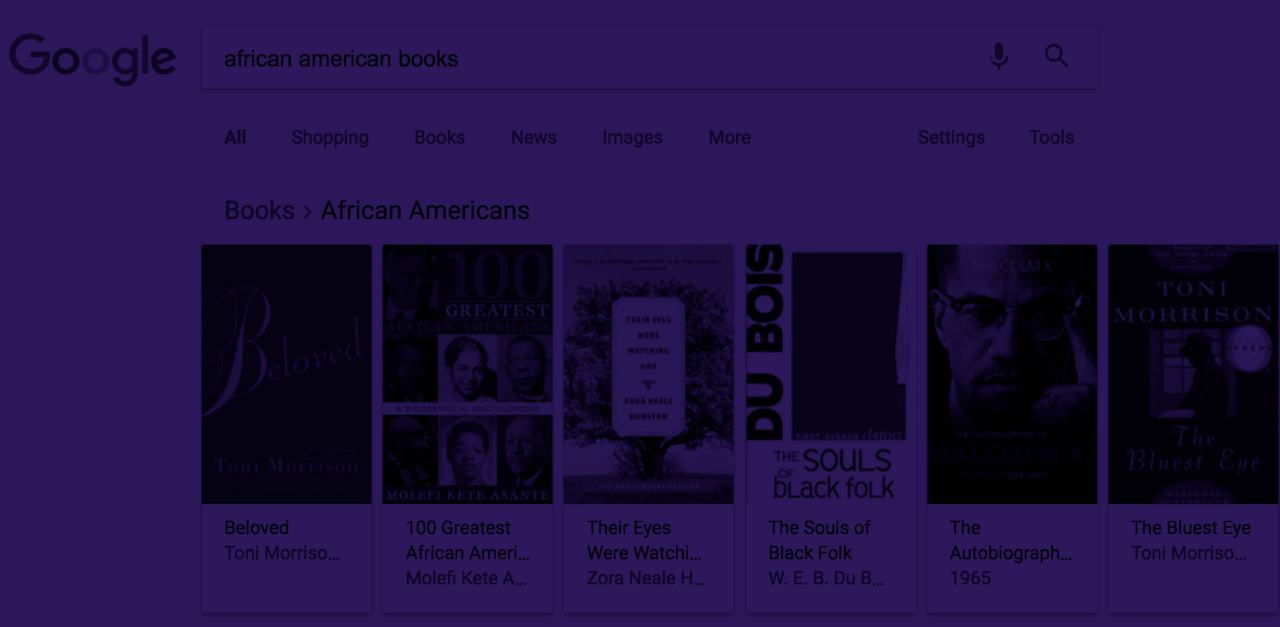

The other change came some time after 2012 — sources estimated it was “years” ago although no one could pin it down precisely — when Google started plugging answers to queries right into its search engine. Search “African-American books” and you’ll get a carousel — a row of images that you can scroll through horizontally — with names and faces right at the top of the search engine results, without having to click through. Search “N. K. Jemisin” and you’ll see an excerpt from her Wikipedia entry with her bio, website, awards she’s earned, and direct links to her books.

Click on one of the links to her books, and Google delivers another carousel of N. K. Jemisin books and related sci-fi books with direct links to buy. This is all found on the first page of Google’s search results on google.com, without needing to click through to AALBC or any other website.

The information is part of what Google calls its Knowledge Graph, its “fact database,” as the blog Search Engine Land put it, and it comes from Wikipedia, the CIA World Factbook, and other sources of structured data. The full list of sources is not public. Knowledge Graph answers are one type of answer that Google displays in a box at the top of its search results, in the space search engine optimization experts refer to as “position zero,” meaning before the first search result. Knowledge Graph is why Johnson believes his traffic has dwindled in spite of the fact that he is on the first page of results for many searches, and why so many of his peers had to fold.

“Expand this across all books sites and you can begin to see how Google has single-[handedly] made the World Wide Web a much less rich place for readers to discover information about books,” he said in an email. “There is nothing that Google had done, or will do, to replace the content Urban Book Source or Rawsistaz produced — or replace the potential AALBC.com lost.” Google declined to comment for this story.

Johnson suspects that Google may have scraped his site to populate its carousels. A search for “African-American childrens books” turns up a carousel of about 50 books at the top of the search results. The books included all appear on Johnson’s “Top 120+ Recommended African-American Children's Books,” which he describes as “a curated list of books selected by a panel of industry professionals.” “Now, I can’t prove Google used my list, but the fact that every book Google is showing is from my list can not be ignored, when one considers the universe of all the books Google could have displayed,” he said in an email.

The similarities in the lists are probably a coincidence. But unfortunately for Johnson, it doesn’t really matter. While he could make an argument that his curation is copyrightable, it would be an uphill battle. The information he presents on his site — book titles with author names and cover images — that Google also presents in its Knowledge Graph result, is not proprietary. His book summaries are written by publishers and are typically the same as the ones used by Amazon and other major book sites. “There is a general piece of advice that I do give to people, which is that if your livelihood is dependent on disseminating public domain information, then your business is very surely in peril,” said Eric Enge, CEO of Stone Temple digital marketing agency, which has studied this trend in search engines. “Because that public domain information is all going to be absorbed into and provided for free by Google. I don’t think there is any hope of stopping that from happening.”

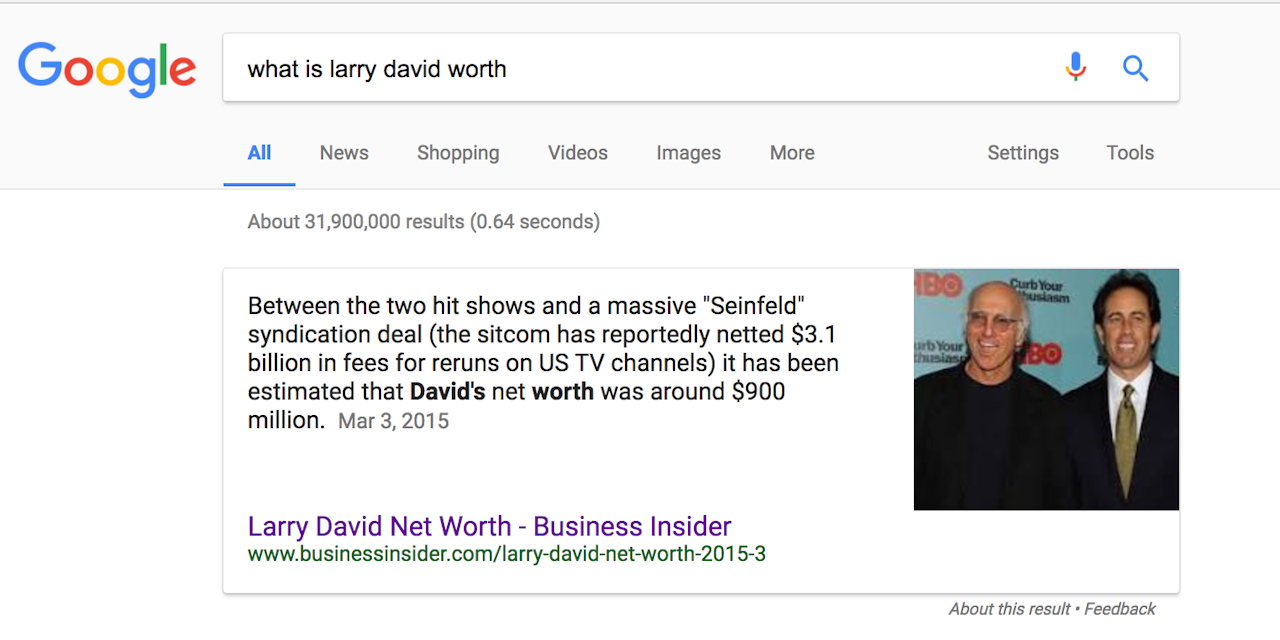

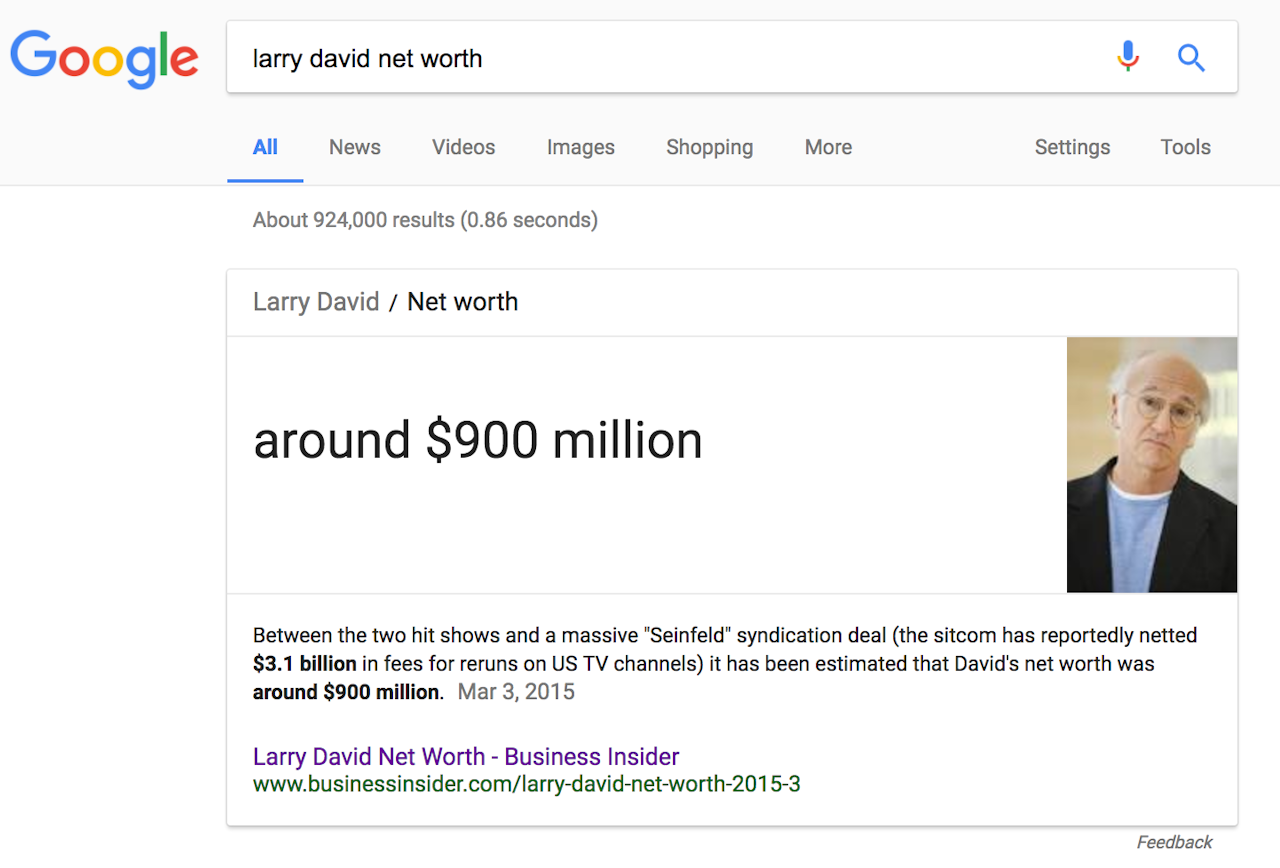

Even when information is proprietary, Google may still hoover it up. Back in April I spoke to Brian Warner, founder of CelebrityNetWorth.com, whose traffic was devastated when Google decided to pull information from his site out onto the first page of search results through a “featured snippet” — an answer box that is similar to Knowledge Graph answers, but sourced to the open web. Google contacted Warner in 2014 to ask if it could have his database of celebrity net worth figures. He declined. Two years later, Google took the data anyway. It started displaying a featured snippet for all of the celebrities on CelebrityNetWorth.com, Warner said, and even a few fake listings he had inserted to test if Google was scraping his site. Even though these snippets were credited to CelebrityNetWorth.com, his traffic plummeted because the net worth for each celebrity was already displayed on google.com without having to click through. Worse, Google is now crediting a site called Bankrate.com in its featured snippets, even though Bankrate.com explicitly credits CelebrityNetWorth’s data.

Google does this because it wants to provide quick, easy to read, high-quality answers to searches without forcing users to scroll through links and dive into third party websites. Indeed, AALBC.com looks very much like a website from the late 90s: it’s a sprawling, 15,000-plus page property made up of busy pages with dense dropdown menus, zillions of internal links pointing back and forth everywhere, and some blurbs that read like they were stuffed with keywords. It’s difficult to distinguish the original content from the stuff that has been syndicated or copied from elsewhere, and AALBC uses Amazon and other affiliate links to sell books in addition to shipping some books directly. By contrast, Google’s presentation of the same information is clean and consistent, especially if users are searching using voice or on a mobile device.

Google argues that this is a better experience for users, and in many cases that is true.

Google’s original mission was to be a searchable directory for the web, but that has been changing. More and more, it’s delivering direct answers so people do not need to dive into primary sources. Google argues that this is a better experience for users, and in many cases that is true. But it seems like a bad long term strategy. Borrowing and remixing has been a tradition on the web forever: The images of authors and book covers on AALBC are borrowed from elsewhere on the web. It’s different when it’s Google doing the borrowing, however. The company has somewhere around 63 percent of the global search engine market share on desktop and as high as 92 percent on mobile, according to third party estimates. When Google aggregates data from the web through Knowledge Graph, featured snippets, and its other answer boxes, it cannibalizes life-threatening amounts of traffic from websites. Google is able to produce these answers because it has the entire web to crowdsource them from. But if all these sites go under, how will Google ensure it has updated information for its answers? Contract with private companies? Hire a research department?

Providing direct answers also saddles Google with new responsibilities. In the past, Google caught some criticism for which sites it promoted, but it’s nothing like the blowback the company is getting for producing inaccurate direct answers. Google has at various times said that Obama is planning a coup, that dolphins are aliens, and that at least four presidents were in the KKK. There are also value judgments embedded in Google’s direct answers. The carousel that pops up for “African-American authors,” for example, is not in chronological order or alphabetical order. It appears to be in order of prominence, according to Google and whatever source it mined them from. The first person in the carousel is Toni Morrison. I’m not disputing that Toni Morrison is the most prominent African-American author, but you could certainly debate it. A debate like that would be pretty new for Google, and pretty weird, and there are infinite permutations of it. The carousel for U.S. presidents is in chronological order, but a search for “Hollywood actors” is not (and the first 14 are all men, by the way).

If you do a search for “African-American authors” and click on Toni Morrison’s face, you will be taken to a Google search for “Toni Morrison.” Johnson compares Google’s behavior here to its behavior for shopping searches, which discouraged searchers from clicking through to websites by prioritizing results from Google’s shopping service at the top of the page and led to a $2.7 billion fine in the E.U. for violating antitrust law. Google’s information about books, sourced from its Knowledge Graph, appears in the same spot — at the top of search results — and on the right side. Since clicking on a book will typically take you to a new Google search, the feature is again promoting Google’s website over others. Google also refers searchers most often to Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and its own Google Play Books store through its Knowledge Graph panels (to its credit, it will also refer you to local libraries for some searches).

Google’s Knowledge Graph answers and featured snippets are useful if you’re trying to find out a quick fact. Websites like AALBC also would never have been viable businesses without Google to send new visitors their way. Johnson acknowledges this, but he still feels that Google is squashing independent voices. In June 2017, when he discovered that the number of websites devoted to black literature had again fallen, he wrote a blog post on AALBC.com called “Black Book Websites Need Love More Than Ever.” Some webmasters moved over to Facebook groups, but Johnson fears that depending on the social network’s platform poses the same existential threat. “As far as I'm concerned,” he wrote, “we are in a crisis situation as far as our representation on the web.”

Corrections: An earlier version of this story said that AALBC.com uses book descriptions from Amazon; those descriptions appear on Amazon but are from publishers. An earlier version also said AALBC.com does not sell books directly; Johnson says he does sell books directly as well as through a variety of affiliates including Amazon and Barnes & Noble.