Governments can’t lay claim to territories in outer space, but corporations can. The 21st century version of the “Space Race” is a commercial satellite race — at least, according to the agenda laid out by the National Space Council meeting this week.

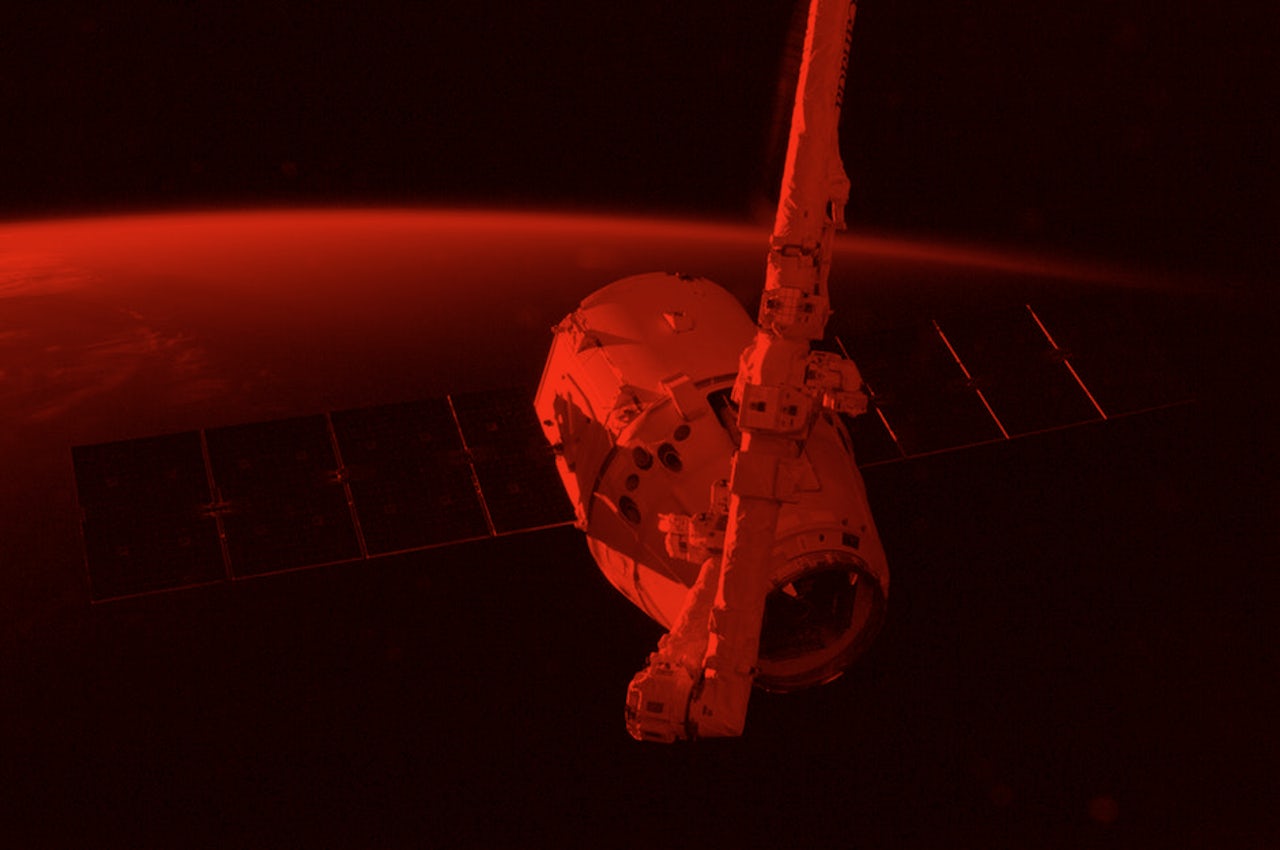

The National Space Council — a Cold War-era space oversight committee relaunched last June after being disbanded and relaunched several times — announced a series of measures designed to make it easier for private companies, such as SpaceX or Blue Origin, to launch satellites into space. Basically, by reducing regulations, the goal is to get as many satellites up in the air as possible.

Per the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, governments aren’t allowed to claim territories in outer space — such as the moon or an asteroid — on behalf of their own countries. However, that doesn’t mean businesses can’t do it. That means the way to promote national dominance in space is to promote space businesses, which in this case, includes commercial satellites.

And America isn’t the only one with this idea. The UK recently launched the UK Space Agency to promote its commercial space sector, and countries like France, Japan, Russia, and China are all investing in this sector as well.

Brian Weeden, the Director of Program Planning for Secure World Foundation, which focuses on sustainability in space ventures, said in a phone call with The Outline that the National Space Council continues a pro-business agenda for the commercial space sector from the Obama administration. American soft power in space is a bipartisan issue.

“On one level, I do think that the US has garnered quite a bit of prestige and soft power because of NASA, the space program, and the International Space Station,” Weeden said. “And certainly quite a bit of hard power through the national security aspect of space. That’s one of the reasons why the US military can have what they have — globalization, global power — is because of space capabilities.”

But the National Space Council is taking crucial steps in making it easier to launch as many satellites as possible, including with technology we’ve never seen before. According to Weeden, one of these steps has to do with "mission authorization" relates to unusual types of space technology. This technology includes asteroid mining technology, which doesn’t exist yet, as well as moon rovers and satellites that refuel other satellites, both of which exist.

Under Obama, authorizing these missions fell under the of the Department of Transportation, which Weeden says has a reputation of prioritizing regulation. Under Trump’s National Space Council, mission authorization is shifting to the jurisdiction of the Department of Commerce, which is known for prioritizing the interests of business over regulation.

Over the next several years, we may see the emergence of asteroid mining technology —an attractive venture for space companies, but one that could produce debris that threatens the safety of people and technology in space. If asteroid mining becomes a reality under these National Space Council policies, these missions could more likely to be approved as missions than they were before.

There are other risks involved with a large number of satellites. Too many radio-emitting satellites can also interfere with one another’s signals, and too many satellites in one area greatly increases the risk of collision. It’s worth noting that SpaceX hopes to launch over 11,000 satellites to provide global broadband internet.

According to Weeden, what’s allowed the US dominates the commercial space sector is the minds, technology, and venture capitalist money of Silicon Valley.

“There’s strong linkages between the commercial space boom and the Silicon Valley boom,” Weeden said. “A lot of the things that are making space better and cheaper are coming from the consumer electronics world, and the vast majority of the capital is coming from the US.”

Obviously, the commercial space sector isn’t only about nationalistic soft power. Valuable radio transmissions, GPS services, and images providing crucial insight to earth’s atmosphere and ecology are all made possible by satellites. And a world where satellites could provide global broadband internet, even to the most remote areas on earth, doesn’t sound like a terrible one.

According to a letter penned by Weeden and Secure World Foundation Project Manager Ian Christensen to Congresspeople on the Space Subcommittee Committee on Science, Space & Technology, there’s a middle ground between laissez-fair and over-regulation, because the success of well-conceived commercial space projects have the potential to benefits US citizens as well as the state.

But politicians actually involved with the National Space Council, such as Newt Gingrich, a White House-appointed advisor, are explicitly framing commercial satellite competition as a “space race.”

National Space Council needs to build off Falcon Heavy momentum and actively pursue public-private partnerships with innovative companies, like @SpaceX, who are out-competing government programs so that America can start winning the space race again. https://t.co/CHbQonzvQKpic.twitter.com/4XsOX5WjIb

— Newt Gingrich (@newtgingrich) February 14, 2018

Granted, Newt Gingrich was a young man at the ripe and tender age of 26 when the US landed on the moon in 1969. He’s a man of the Cold War. But Gingrich’s attitude may reflects the priorities being demonstrated by the National Space Council generally: the commercial space sector is an area for American soft power.