I’d like to start with a game. It’s called Who Wrote This Passage?

a) “All writers under censorship are at least potentially touched by paranoia, not just those who have had their work suppressed.”

b) “Most chillingly, the fear of censorship, which kills some ideas even before they are hatched, also makes the full effects of censorship ultimately unarchivable.”

c) “It’s impossible to gauge the degree of… censorship going on behind the scenes at publishing companies and literary agencies… Equally impossible to gauge is the extent of writers’ collective self-censorship.”

If for a), you guessed “South African Nobel Laureate J.M. Coetzee describing his experience as a writer working under state censorship in apartheid South Africa from the mid ’70s,” you would be right. For b), if you guessed “Stanford professor Jonathan Abel’s authoritative account of different modes of state censorship in Transwar Japan,” then you would again have nailed it. And if for c) you guessed “Lionel Shriver going off-piste in the March 2018 issue of Prospect magazine,” then it is my bitter duty to inform you that, once more, you are correct.

Bonus round: “We must stand up for fiction as a place where transgressive behavior and ideas can be explored. We must stand up for freedom in the arts. I think we have to be willing to stand up for the despised.” Is this the celebrated South African Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer in 1980, talking about the role of the writer in the struggle against apartheid? Or. Is it the vampire writer Anne Rice, in 2015, on Facebook, talking about Christ knows what? The answer will not surprise you.

I cheated a tiny bit, just to make the game “fun.” If I had left the words “politically correct” in passage c), you would have immediately recognized what it was: yet another example of present-day writers and commentators drawing false equivalences between “liberal attempts to suppress free speech” and censorship, between “the PC police” and the real police, between “the current campus KGB, rapidly radiating into the larger culture” and the actual KGB. Blithely drawing these comparisons is by no means a new strategy, but it does seem that people are becoming increasingly keen on it. As Josephine Livingstone recently observed in the New Republic, “casual references to twentieth century totalitarianism have been cropping up lately like clover in the lawn.” Comparing “the mob of snitches who went after Bari Weiss” to the Stasi like it’s nothing. Comparing “Twitter feminists” to Maoists without dying of shame.

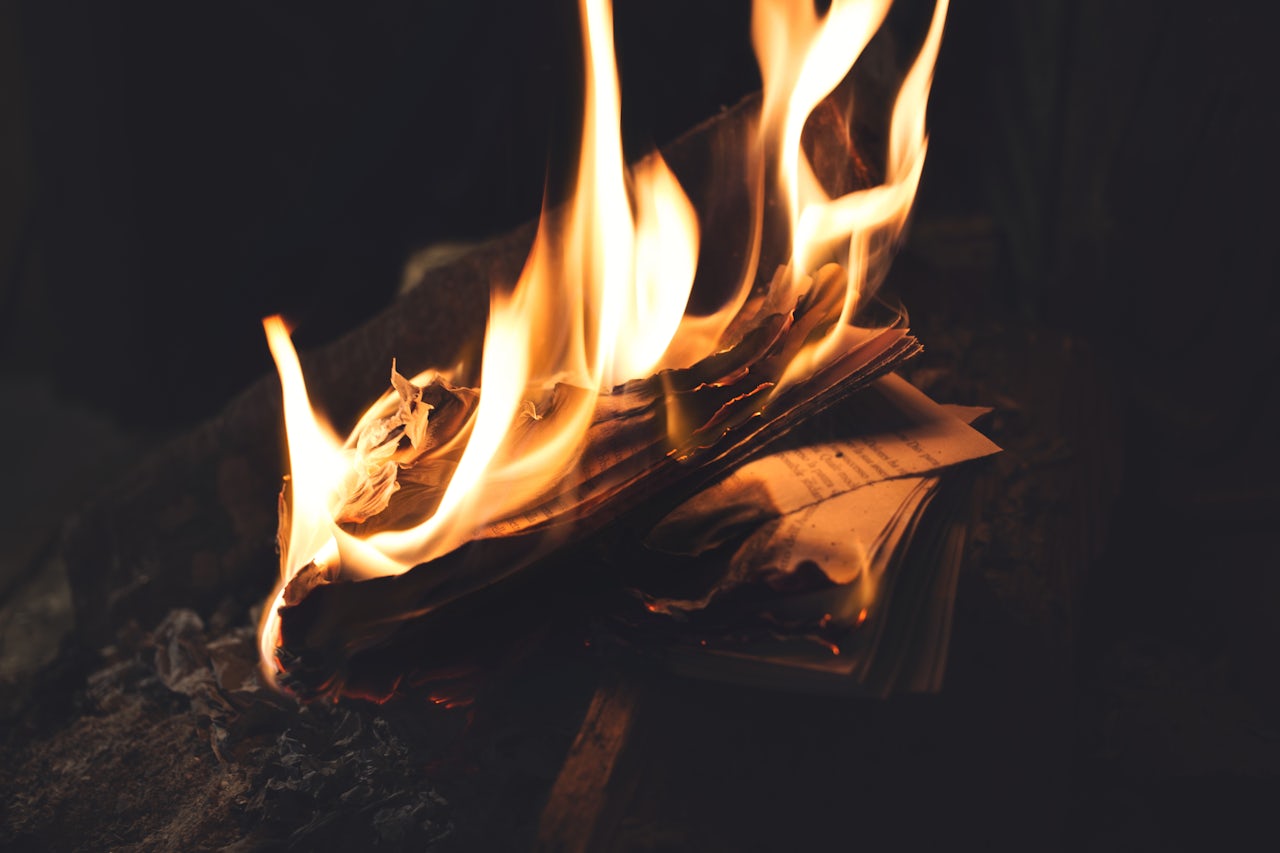

It’s not just references to 20th-century totalitarianism. It feels like the Shrivers of this world are sitting there flicking through a coffee table book called Annihilating Acts of Violence Meted Out by Authoritarian Powers Over the Millennia and just randomly picking a page. The New York Times’ resident provocateur Bari Weiss comparing students shouting over a guest lecturer to an auto-da-fé. The anti-feminist feminist Katie Roiphe in Harper’s, comparing the anger over her potentially outing the then-anonymous creator of the “Shitty Media Men” list to the Dreyfus Affair, an emblematic miscarriage of justice in the late-19th century. Alfred Dreyfus: stripped of his rank, chained up on Devil’s Island for five years in appalling conditions, ultimately exonerated due to the efforts of those right-thinking people who could see that the accusations against him were baseless, motivated only by spite and envy. Katie Roiphe: “Alfred Dreyfus c’est moi.”

How do people compare “Twitter feminists” to Maoists without dying of shame?

Some of these comparisons are easy to bat away. It is the work of a moment to say “Katie Roiphe, being shouted at on Twitter is not the same as being sent to jail on a pestilential island” or, “Bari Weiss, being shouted at in person is not the same as being set on fire and killed for your beliefs.” It seems that other comparisons are not so quickly dismissed. Here comes old Lionel riding in again: “The students running campuses like re-education camps aren’t afraid of being muzzled, because they imagine they will always be the ones doing the muzzling… These millennials don’t fear censorship because they plan on doing all the censoring.” If you asked Lionel Shriver very politely, you might get her to admit that a university campus is not really at all the same as a re-education camp.

You might have to work a bit harder, however, to get Shriver to make any real distinction between “politically correct censorship” and “state censorship.” Judging by her volubility on the subject, it is doubtful whether Shriver would do so, or concede that a government with the legally mandated authority to ban any text for any reason was in fact more powerful than… millennials on the internet, I guess.

This is the problem with the “politically correct censorship is somehow the same thing as actual censorship” argument: the terms are never defined. When Shriver says she worries about her work being “censored,” does she mean she is worried about her books being banned, or parts of them being redacted? Perhaps she is frightened that she will be subjected to the same treatment as Alex La Guma, a South African novelist who was banned under the terms of the 1950 Suppression of Communism Act, placed under house arrest, and finally forced into exile. La Guma’s banning meant that nothing he said or wrote could be published within South Africa, but despite the automatic proscription, the censors looked over everything he wrote anyway, and then banned it just to be on the safe side.

This is the problem with the “politically correct censorship is somehow the same thing as actual censorship” argument: the terms are never defined.

So, is Shriver worried that the police will use ownership of her books as justification to arrest and detain activists without trial, as happened in apartheid South Africa? When she says “these millennials plan on doing all the censoring,” does she mean that these millennials plan on organizing themselves into a highly complex bureaucratic system that will oversee the banning of more than 11,000 novels, as happened in apartheid South Africa? Or, rather, does she simply mean she is worried that some people won’t buy them, or that she would not like it very much if someone came and waved a sassy poster outside one of her readings? Hmm?

If one were casting around for a rebuttal to the “politically correct censorship is actually just the exact same thing as official state censorship and represents the same kind of violation of a person’s rights,” the linear kilometer of documents left behind by the apartheid censors would be a good place to start.

The creation of the 1963 Publications and Entertainments Act allowed the apartheid state to operate one of the most rigorous censorship systems in the world. The censors banned tens of thousands of novels, magazines, periodicals, and other forms of printed matter. The list of writers whose work they banned included everyone from de Beauvoir to Joyce to Updike. They banned novels on the grounds that they were pornographic, or seditious, or “harmful to relations between inhabitants of the Republic.” They banned novels just because they didn’t like the look of them, or because they were feeling testy that day. They banned novels critical of apartheid because such novels would give black South Africans “the wrong idea” about the conditions they were living in. They were not required to furnish any reasons for their decisions. Once the decision had been taken to ban a book, a notice was published in the official organ of government, the Government Gazette, and the Jacobsen’s Index of Banned Books was updated. The end.

“Call-out culture” is not the same as this. The apartheid censors banned thousands of books because they were justifiably terrified that the free circulation of ideas would hasten the demise of white minority rule. They successfully fought against that inevitable demise for almost thirty years, empowered by legislation which expressly excluded the possibility of a writer or publisher appealing to the courts. Using the apartheid censorship system as a basis for comparison (or the Australian system, or the Irish one, or the one in Bourbon France, or colonial India, or East Germany, or Tsarist Russia, or the USSR), it’s hard to imagine how anyone could convincingly argue that Bari Weiss being yelled at for many days on Twitter has anything in common with censorship, at all. The comparison keeps getting made, though, so we must challenge it.

Unsentimentally discussing the deification of banned writers in South Africa and the USSR, Coetzee asks “whether writers under censorship are wholly disinterested in presenting themselves as embattled and outnumbered, confronting a gigantic foe.” In his 1984 essay “Turkish Tales,” the writer and academic Njabulo Ndebele describes what this kind of self-presentation looks like in the wild: “I once met a writer who gleefully told me how honoured he felt that his book of poetry had been banned by the South African censors. What I found disturbing was the ease with which the writer ascribed some kind of heroism to himself, almost glorying in a negation.” A kind of de facto heroism is conferred on banned writers by way of a binary view which insists that because censors are stupid and wrong, every writer whose work is banned is morally as well as intellectually above reproach. In this view, writers are beacons of light and truth simply by virtue of their profession.

It’s easy to see how this plays out today. The cloak of martyrdom can be awfully becoming, and when writers like Shriver and Roiphe talk about being victimized, or of being like Alfred Dreyfus, they are helping themselves to the same kind of honor that was afforded to writers like Gordimer and Andre Brink.

Shriver in particular seems determined to present herself as an impish agent of chaos, merrily kickflipping over staid orthodoxies of taste, capering around like some kind of Squirrel Nutkin-type figure in her quest to Tell It Like It Is. She uses the word “mischievous” a lot. The word “fun.” Wheeeee. She refers to herself as “obstreperous.” A “renowned iconoclast.” YOU might be shuffling haltingly forward to place your squalid offering at the foot of The Political Correctness God/dess. She, meanwhile, is surfing the crest of a wave of irreverent lols, and has no time for your timid supplicating gestures towards whatever outlandish notions of quote unquote political correctness you have come up with on the spot right this minute. See Shriver, on her skateboard, wearing her little sombrero. An iconoclast. A legend. This love of whimsy and mischief and The Truth seems primarily to express itself in her vocal support of Brexit, but never mind.

The cloak of martyrdom can be awfully becoming.

The most commonly invoked rebuttal to the view that “politically correct censorship is the same as actual censorship” is the one which suggests that even if there is some kind of small-c censorship being currently enacted, it’s okay, because the censorious drive this time around is motivated by decency and a will to respect the wishes of others. This argument means well, but it misses the point, and sustains the notion that what “happened” to Weiss or Roiphe or Shriver is a species of censorship. It can’t be, if the term is to retain any meaning at all.

Condemnation of shitty opinions isn’t censorship. Being shouted at lustily in public isn’t censorship. To suggest that they are the same is a betrayal of the victims of actual censorship regimes, in the same way that comparing a “Twitter mob” to a lynch mob is a betrayal.