In August 2010, Purdue Pharma, producer of the addictive painkiller OxyContin, temporarily pulled the drug off the market and replaced it with a version that was more difficult to abuse. Noticing that OxyContin pills could be crushed into a fine powder and then smoked, injected, or snorted for a quicker onset, Purdue created an “abuse-deterrent formulation” that instead turns into a gummy paste when crushed. This, along with a recent government-mandated crackdown on opioid prescriptions and the shuttering of “pill mills,” has likely contributed to a decrease in prescription opioid-related deaths over the past eight years.

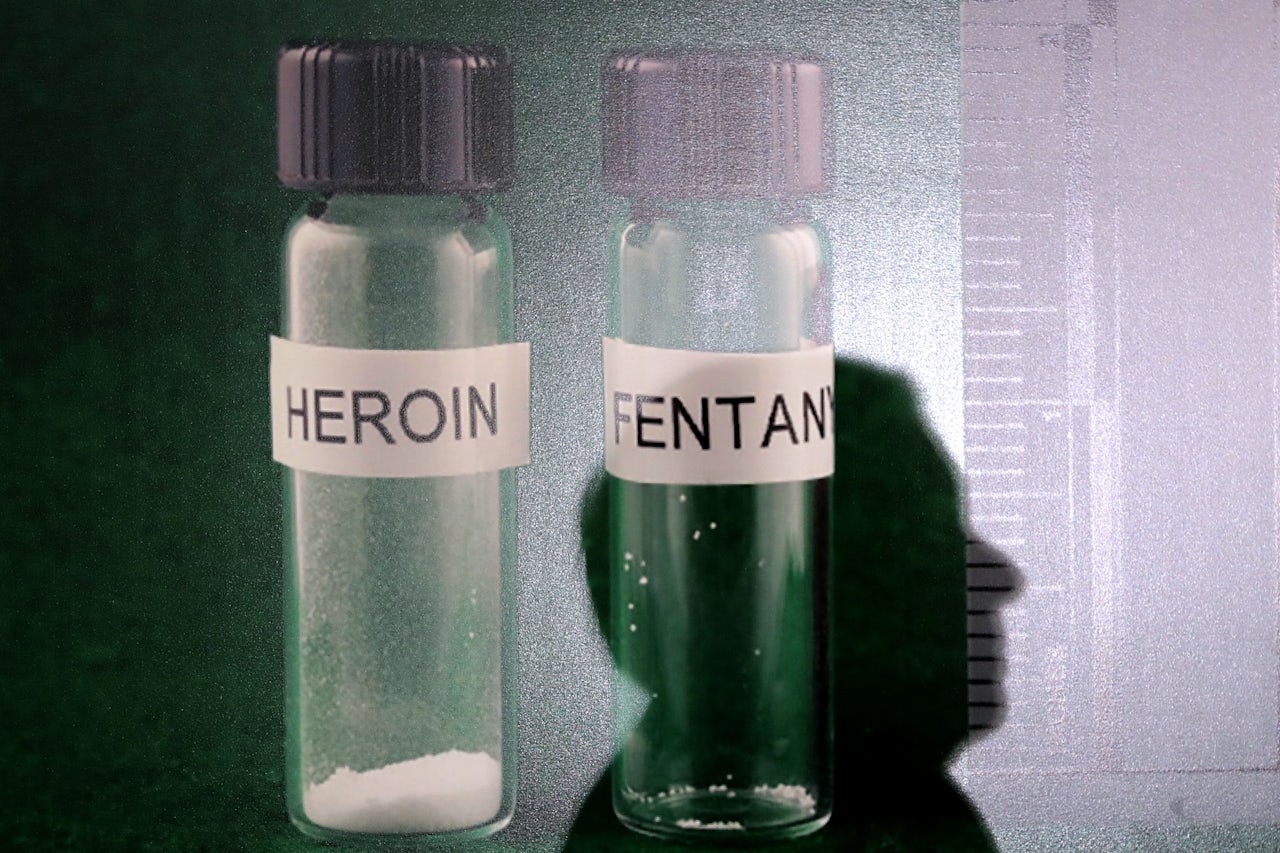

But according to a new study by researchers at the University of Notre Dame and Boston University, this reformulation may have inadvertently encouraged some users to turn to heroin, contributing to the quadrupling of heroin related deaths between 2010 and 2015.

Looking at data on overdose deaths from 2004 to 2014, the researchers discovered that after prescription opioid-related deaths started stagnating, the rate of deadly heroin overdoses began rising. William Evans, one of the co-authors of the study and an economics professor at Notre Dame, said in a statement that the reformulation of OxyContin was not a sufficient way of curbing opioid deaths. “Although the abuse-deterrent formulation for OxyContin reduced prescription opioid mortality,” Evans said, “the movement to heroin as a result of the reformulation meant there was a one-for-one substitution of heroin deaths for opioid deaths.”

A similar study by the American Action Forum, which was first reported by The Washington Post on Wednesday, suggests that after doctors cut down on opioid prescriptions, heroin and fentanyl dealers stepped in the fill the void. Like the Notre Dame/Boston University study, the American Action Forum study suggests a possible correlation between the sharp decrease in prescription opioid consumption in 2010 and the staggering rise in deadly heroin and fentanyl overdoses in the years that followed.

“Say policymakers were to start turning more attention to the supply of illicit opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids, which is obviously something that needs to happen,” Ben Gitis, a co-author of the American Action Forum study, told the Post; “Doing that without addressing dependency could turn users to other types of drugs to use in their addiction. Really, the root cause is the dependency itself.”

In addition to the more obvious risks, like addiction and potential overdose, heroin use comes with its own specific set of problems, particularly in cases where people inject it. Re-using needles can result in infection and the transmission of disease, and users who don’t clean their skin before injecting can develop abscesses. In some cities, including Seattle and Philadelphia, officials are considering establishing safe injection sites where people can use drugs with sterile equipment — and where staffers have access to overdose antidotes like naloxone, which would prevent overdoses and deaths.

According to the Notre Dame researchers, focusing on treatment and addiction programs may be a more effective use of resources.

“From the policy perspective, what we’re finding is that these abuse-deterrent formations really aren’t going to reduce death rates in the near future, because there are alternatives out there that people can use,” Ethan Lieber, one of the co-authors of the study and economics professor at the University of Notre Dame, told The Outline. “So if we’re thinking about where we want to put our efforts in terms of making policy — or where we want to put our money — it’s probably not in these abuse-deterrent formulations, so much as other programs that are working on treatment or prevention.”