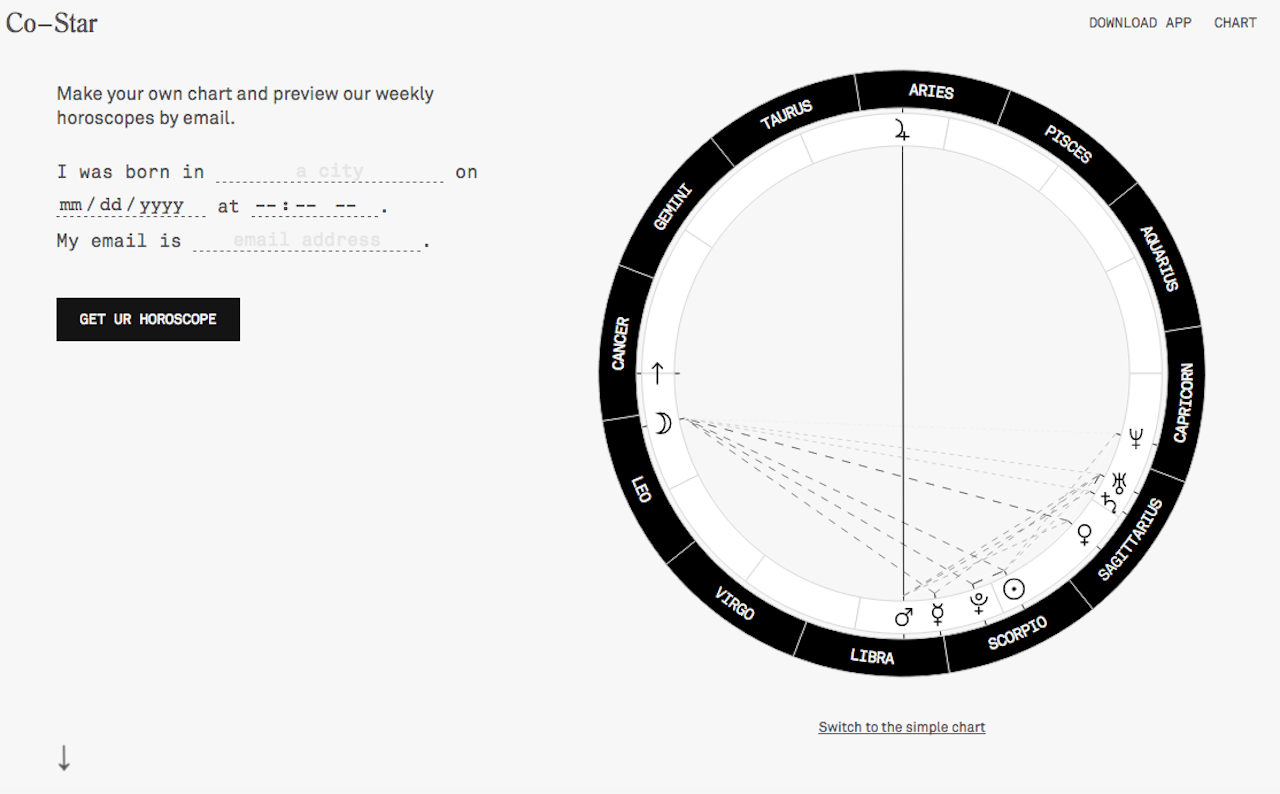

Personalized horoscopes have never been easier to get than they are right now. People don’t have to buy a magazine. They don’t even have to Google it. Just download a free app from the iOS App Store or Google Play, and access it at any moment. There are dozens upon dozens of popular options: Co–Star, which has a social component, The DailyHoroscope, one of the top results for horoscope apps in the iOS App Store, Oscar & Jonathan Cainer Horoscopes, which emphasizes its visual presentation, and many, many others.

In order to get started, all you have to do is submit a few pieces of personally identifiable information. Name. Gender. Birth city. Birth time. Birth day. Current location. Email address. And for horoscope apps with a social component, such as Co–Star, your phone contacts. Wait a minute.

This isn’t the only type of information that horoscope apps collect. The DailyHoroscope’s privacy policy states that it gathers your location information. iHoroscope needs the user’s gender. AstroSage Kundli (who did not respond for comment) requires your current residence. While horoscope apps may be considered “entertainment” apps by the iOS App Store and Google Play, the information they require is very personal and very real.

The iOS App Store and Google Play don’t take a hands-on approach to governing and protecting user information; instead it’s outsourced to individual app privacy policies, which aren’t clear about exactly who gets access to this information or how it may be used.

Personal information could go to data brokers, data analytics firms (similar to those of Cambridge Analytica), and advertisers. The risk of this information sharing is higher for women and people of color, who according to Pew Research Center, are both more likely to believe in astrology.

When reached for comment, DailyHoroscope app developer Comitic said that their business affiliates include various advertising agencies.

“We prefer to work with largest and most respected ad networks,” a Comitic representative said in an email. “We prefer to work with ad networks that employ contextual advertising rather than user directed advertising.”

Co–Star CEO Banu Guler said in an email that user data is not “sold” or “shared” with third parties or business affiliates. However, its privacy policy states that this information is “shared” with employees, third parties, and business affiliates. Co–Star did not clarify exactly who these contractors and affiliated organizations are.

Depending on exactly how these third parties handle user data, people could be at a higher risk of identity theft, doxxing, harassment. Personal information could also be sold to third parties that are involved with job recruiting and advertising. For women, who are more likely to be shown ads for lower-paying jobs, and people of color, who are more likely than white people to have arrest records appear in search engine results, there are tangible economic risks associated with where their information goes.

The privacy policies of many horoscope apps claim that sensitive information is “anonymized” and therefore can’t be traced back to an individual. But that’s not necessarily true in practice.

According to a phone call with Natasha Tusikov, a York University professor of law and technology, if third parties have information on a person from multiple apps, websites, and sources, they can cross-reference the data and re-identify people.

“This is a very serious concern if women have abusive partners they've escaped, they have restraining orders against people, or don't want people to know exactly where they live or work,” Tusikov said. “Re-identifying information is a very key privacy issue now, [but] this is something companies like to downplay because their entire business model rests on distributing or anonymized information.”

The iOS App Store and Google Play require app developers to tell users what information they give to third parties and the circumstances under which that would happen. But the privacy policies may use broad phrases such as “business affiliates,” “affiliated organizations,” and “contractors” and are not required to be more specific. Neither Apple nor Google responded for comment.

The privacy risks of horoscope apps don’t just concern the people who use them. Astrology frequently involves compatibility assessments, which requires information about family, friends, and romantic partners. According to Tusikov, disclosing that kind of information could put those people at risk as well.

“When we talk about astrology apps, some people think, 'well, I'm only giving up information about me,'” Tusikov said. “But if they're answering questions about siblings, parents, partners they're interested in, past partners, current partners—they're actually giving up quite a bit of information about other people, who may not know that their information is being held.”

It’s also common for horoscope forecasts to include information about help or connect users to human “psychic” services. If users ask for advice about, say, an illness, their fitness, or their weight, it’s possible for horoscope services to have glean medical information about an individual. (Even though there is no proven medical validity of horoscopes, astrology, or psychic services.) For instance, the app iHoroscope, a product of easyhoroscope.com, expressly encourages ‘live readings” where users make a paid call for psychic services. And Chaturanga encourages users to have “confidential” chats with professional astrologers and disclose information about their "personal relationships," "place to live," and "career or business."

It’s not uncommon for privacy policies to be ripped, almost verbatim, from generic sources when companies can’t be bothered to write their own. This makes it extremely unclear to as to whether the policies are actually being followed in practice. For instance, Co–Star’s privacy policy matches that of WordPress.org identically, with the exception of the company name. The app Yoda Love Astrology has a privacy policy that is identical to “MyPsychic,” a different app. The privacy policy for iHoroscope borrows heavily from standard privacy policy language used in many other places—such as Health Talks Online, CMEF, and many other services not related to astrology.

But horoscope apps are considered “entertainment” apps by the iOS App Store and Google Play, and their information isn’t considered “medical” in the eyes of the law. That means that the information isn’t subject to additional protections given to health information, such as The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, which limits the storage and use of medical information to necessary medical uses only.

Many apps also do not disclose precisely how long they keep people’s data. Apps such as iHoroscope claim that they keep user information “for as long as your account is active or as needed to provide you services,” with “services” never clearly defined. However, the privacy policy mentions affiliations with credit card processors, email distributors, and live psychic operator services—all parties which could get access to certain user data. So it’s not obvious how long information is kept, even if a user deletes their account.

Let’s say that a user doesn’t delete their account. After all, astrology apps that provide daily forecasts can easily become incorporated into a person’s daily routine. The longer you keep the app, the more information accumulates. For instance, new friends, new romantic partners, or health information, if disclosed.

“Say you're someone who has a lifelong interest in astrology, and you've used an app for a number of years—that's a massive amount of information on you,” Tusikov said. “On your daily life, habits, very personal information. The more information that that company has on you, the greater the problem if that information leaked, or breached, or if that company suddenly folds.”

The scale of these problems is only getting bigger. Young people have historically been more likely to be interested in astrology than older adults. And it’s not difficult to notice that astrology become more prominent among Millennials and Gen Z in recent years. Women are the bigger audience for astrological content, and are also more likely to be victims of identity theft and salacious online harassment, and people of color are disproportionately more likely to be surveilled, especially in the context of social activism.

Although horoscope apps market themselves as tools of self-care and actualization, , they’re still curated and distributed by companies concerned with increasing their profit margins. And vaguely worded privacy policies that allow them to gather and distribute user information is a way of accomplishing that.

Nearly every app leverages their privacy policies in this way. However, there’s a particular bitterness in fact that the people more likely to use astrology apps are also the people who face the highest risk when that information isn’t protected.