More than 40 percent of the global population, more than 2 billion people, have a dust problem. Not “dust” meaning the grey puffs under the couch, but the dust of the Dust Bowl: microscopic soil particles, less than 0.05 millimeters across, so small that they get hoisted up into the wind and end up in people’s lungs.

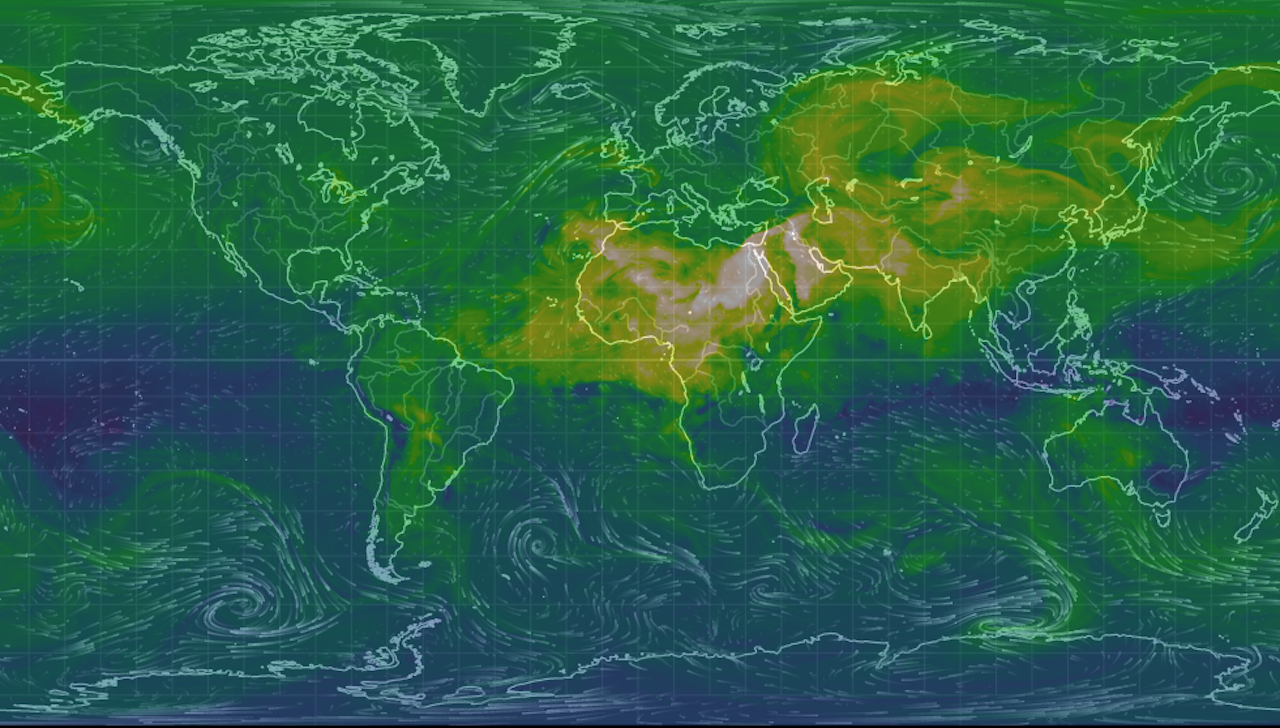

We know that large amounts of dust are linked to premature death. However, climate change is expected to make the problem much worse in the next century, and scientists still don’t know how much. In the next century, the lethal range of dust is expected to proliferate. Between now and 2050, the many as 4 billion people, half the world’s population, are expected to live in drylands. It’s not because people are migrating there. Drylands are growing because of (you guessed it) climate change.

According to a research letter in Nature published in May from scientists from Harvard and George Washington University, airborne dust levels are expected to proliferate by 30 percent by 2100 due to climate change, and dust-related premature deaths could go up by as much as 130 percent.

“Despite [health] concerns, few studies have examined the impacts on air quality and public health of the projected hydroclimate changes in the southwestern United States,” the study reads.

As global warming speeds up evaporation, freshwater resources are expected to dry up around the world. This sets off a vicious cycle: Compared to, say, a tropical rainforest, dry soil and dust particles absorb less carbon dioxide from the air. As a result, dry, dust-prone areas actively keep themselves that way.

In excess, dust has been linked to not just asthma, lung disease, fibrosis, lung cancer, and difficulty breathing, but heart disease, heart attacks, and irregular heart beats. These health risks are a fact of life for people who live in “drylands,” or swaths of land that get little rain, has dry soil, and doesn’t have much plantlife. This doesn’t just include desserts, but also grasslands and prairies.

By the end of the twenty-first century, as much as half of the world’s landmass could be covered by drylands, especially in economically vulnerable areas in South America, Africa, and Mediterranean-bordering countries.

The most vulnerable areas are dangerously understudied. According to a research review from the University of Namur in Belgium, we still don’t understand the extremity of how climate change-driven dust from the largest desert, the Sahara, will hurt human health.

“[This paper] reveals an imbalance between the areas most exposed to dust and the areas most studied in terms of health effects,” write the authors. “None of these studies has been conducted in West Africa, despite the proximity of the Sahara, which produces about half of the yearly global mineral dust.”

According to a research review published in Environ Health in 2017, even socially and economically privileged areas, such as Europe, are a climate change dust blind spot. “There are few studies on health effects associated with climate change impacts alone on air quality,” the paper reads, “but these report higher [aerosol]-related health burdens in polluted populated regions and greater [dust] health burdens in these [European] emission regions.”

Since 1997, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has regulated the amount of particulate matter—microscopic matter which includes soil dust, as well as other human-made chemical pollutants. In fact, the U.S. and other wealthy countries around the world have made curbing air pollution a priority for people in their countries. But regulating microscopic matter from factories won’t stop the larger force of climate change-driven desertification and the risk it presents to human health.