No one told inmates in Colorado why their tablets were being taken away. On August 1, around two years after the Colorado Department of Corrections rolled out its much-hyped program “gifting” every inmate in the state a free iPad-esque tablet, the CDOC suddenly decommissioned them. Nearly all of the 18,000 tablets distributed to inmates across state prisons were removed. A spokesperson told the Denver Post that the tablets were pulled due to “unforeseen security issues.”

Less than a week before Colorado pulled its tablets, a group of 364 inmates in Idaho exploited a security flaw in their tablets and transferred $225,000 into their own accounts, according to a report by the AP. A spokesperson for the Idaho Department of Corrections told The Outline that the inmates have been charged with a “Class B disciplinary offense” — a charge that can carry with it a transfer from a minimum-security to a medium-security prison. (In Colorado, the CDOC claims that the two incidents were not related, but it would not comment on the security reasons the tablets were pulled.)

Since 2016, prison telecommunications companies like JPay and Global Tel Link have been giving out thousands of free tablets to inmates in several states, including New York, Florida, Missouri, Indiana, Connecticut, and Georgia. While the tablets are marketed as ways to let inmates educate themselves, prepare to re-enter the workforce, and communicate with their loved ones, the economics behind what has become a free-tablet imbroglio suggest that in some cases the operation is no more than a money grab for every player in the chain, from state governments to the distributors.

The tablets feature each company’s unique online marketplace, which is something like an iTunes/Venmo/Gmail mashup, allowing inmates to send emails, video chat, receive money transfers, and download select movies, TV shows, and music. Most tablets block internet access, though in some states inmates are allowed to visit online libraries and news sites. And though tablets are typically custom to the telecommunications companies, some operate out of established systems like the Google Nexus 7.

Colorado was the first state to adopt a free tablets program in 2016. At the time, the pitch from telecommunications company JPay was purely charitable: inmates would get a way to connect to the outside world, and prisons said that the tablets would “improve [prisoners’] behavior,” leading to safer environments. The tablets also came equipped with education programs and online law libraries, all of which would be provided to inmates for free. The price point was difficult to argue with.

Yet for many inmates and their families, that price tag has not panned out as promised. “It’s very misleading to call them free,” said Stephen Raher, a lawyer and volunteer at the Prison Policy Initiative who researches communication systems in prison. “I get that there are some systems where you might get the tablets free of charge, but if you want to do anything with that tablet, you have to pay, and the prices are eye-raising for anyone, but especially for people earning 40 cents, $2 a day.”

In New York, for example, JPay — which aspires to be the “Apple of prisons” — gave out 52,000 free tablets in February 2018. By 2022, it expects to make all of that money back plus $9 million in profit, according to internal company documents. That’s because of the way it has priced even its most basic inmate services.

JPay charges an additional $4.15 service fee to transfer $20 from the outside to an inmate. Sending one email costs $.35, double that to include a photo, and quadruple to include a video. A song can cost up to $2.50, and an album can be — somewhat inexplicably — as much as $46. Chat with a loved one? That’ll be $18 per hour. But even these prices fluctuate during busy seasons. For instance, WIREDreported that the price of an email might increase from $.35 to $.47 around Mother’s Day, when inmates most want to communicate with loved ones.

“It’s prices that are way over market rates, and it just seems like predatory pricing, just pure profit-seeking,” said Raher. “That’s money that needs to come from family members, and usually there's a fee associated with sending it to someone’s commissary account. It's a very predatory system.”

As of January 2017, fees related to money transfers alone generated an estimated $99.2 million in revenue for companies like JPay, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. The average fee was about 10 percent. This all comes from the coffers of inmates, who earn an average of $.92 per hour for their labor, and families of inmates, who tend to be much poorer than average families. Family members of inmates who requested anonymity told the The Outline that as much as 25 percent of their monthly income went to paying for phone calls, video chats, and digital commissary items like games.

JPay is owned by Securus, a conglomerate of prison tech companies notorious for tracking U.S. cell-phones and for its security vulnerabilities that exposed the mobile data of potentially every American to hackers in May 2018. (Securus is operated by Tom Gores, the billionaire owner of the Detroit Pistons, who acquired it in November 2017 for $1.5 billion.)

Securus’ main competitor is Global Tel Link, a powerful telecommunications company familiar to listeners of the podcast Serial (“This is a Global Tel Link prepaid call from…”). If recent acquisitions are approved, Securus and GTL will have a combined share of as much as 84 percent of the prison telecommunications market. Securus and GTL are responsible for the predatory pricing of prison phone calls; in some states, a 25-minute phone call can cost as much as $15. They're also behind the vast majority of prison tablets.

Companies like JPay and GTL often sign contracts with entire state prison systems, and prisoners have no choice but to use whichever company is chosen for them. Many states earn a portion of the revenue generated from prisoners using the tablets, so the incentive is to pick the company with the highest prices: the more that a telecommunications company makes off the inmates, the more the prison makes.

Prisons earn back anywhere from 10 to 50 percent of the revenue generated from emails sent by the people they incarcerate. For instance, GTL introduced free tablets in Indiana last year, from which it expects to make $6.5 million — including a sizable cut, $750,000 per year, for the state. Securus, meanwhile, has paid out $1.3 billion in commissions to prisons over the last 10 years (a number that includes commissions for non-tablet programs, including phone calls).

Both companies allegedly use that money in exchange for political favors: the Mississippi attorney general accused GTL of bribing the state’s main corrections officer with commissions so that he would cut more lucrative contracts with the company. (GTL settled for $2.5 million in August 2017.)

Even the truly free services offered by the prisons, including online libraries and education programs, have come under fire. Many prisons have scrapped their physical law libraries, but the online libraries that have replaced them often lack the legal resources inmates need, according to an investigation by The Crime Report. The legal services offered through the tablets have also malfunctioned so frequently that countless incarcerated people have been left without proper legal aid.

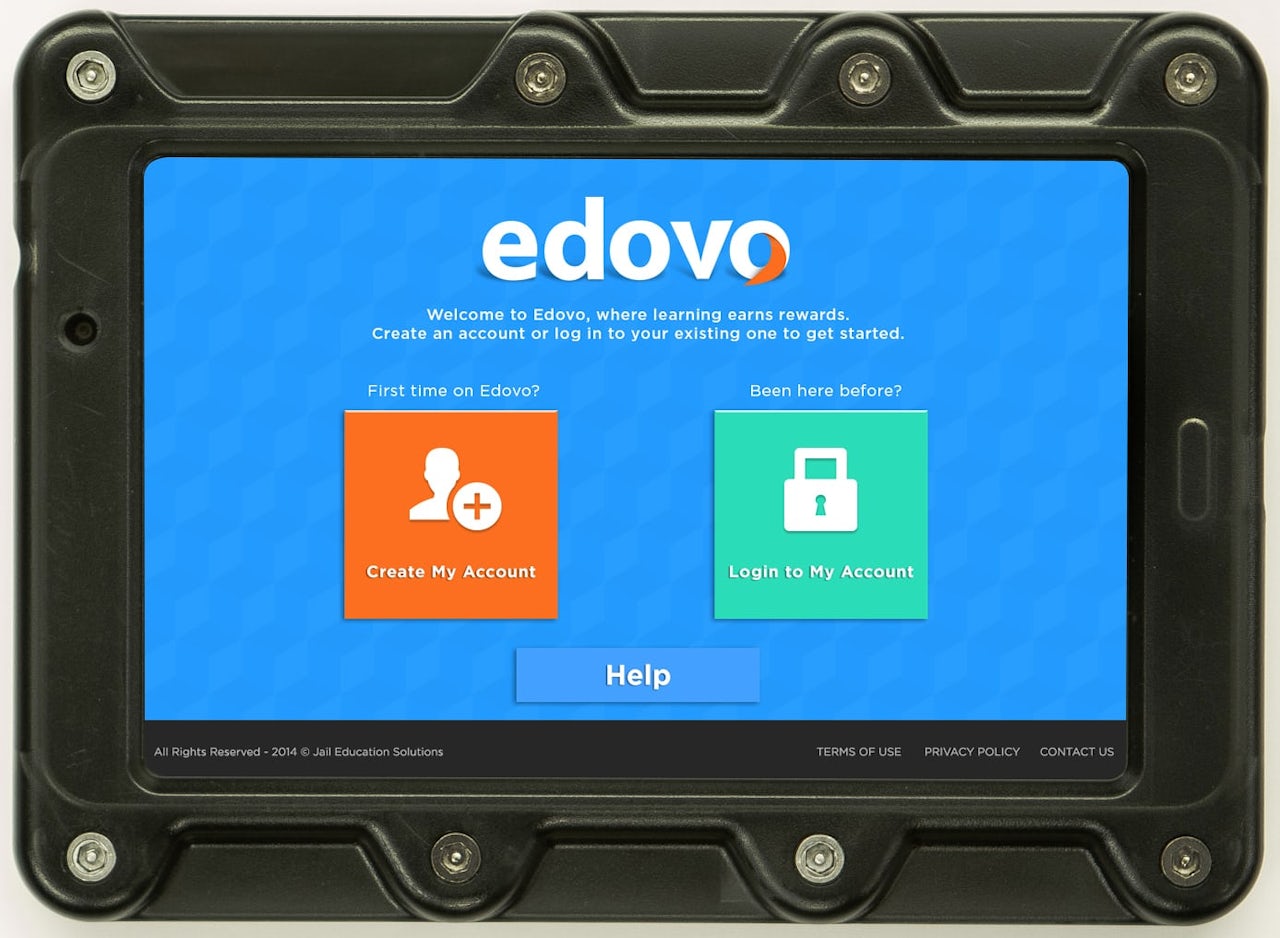

And those education programs are getting similarly negative reviews. Brian Hill, CEO of Edovo, a startup that has competed with JPay and GTL to bring educational tools to incarcerated people, told The Outline that their education programs aren’t well-planned — “really, it’s a PDF and video dump of whatever content they can find,” he said. “At the end of the day, they don’t care,” added Hill. “They’re big and they’re clunky and they don’t try very hard.”

Some telecommunications companies have explicitly marketed the tablets to prisons as a way to uncover inmate crimes. A 2013 report from telecommunications company Telmate noted, “[t]he more an inmate communicates, the more likely he or she will self incriminate.”

GTL reserves the right to use inmate data “any business or marketing purpose,” while Securus expects its customers to “have no expectation of privacy” because “correctional facilities can distribute, transfer, or even sell content and related information to other parties,” as the Prison Policy Institute noted. Another company, Smart Communications, has no real policy except to say it won’t share credit card information.

Privacy violations are not hypothetical, either: in a June 2018 lawsuit, Securus was charged with recording private conversations between incarcerated people and their lawyers and sharing them with prosecutors, a violation of their attorney-client privilege.

Many incarcerated people appreciate the ease of communication that the tablets allow for, according to family members who spoke to The Outline, and future tech reformers can cater to those desires without levying such exorbitant charges on — and laying claim to the data of — a population that quite literally has nowhere else to go. Free isn’t free in a prison system that has routinely profited off of inmate labor.