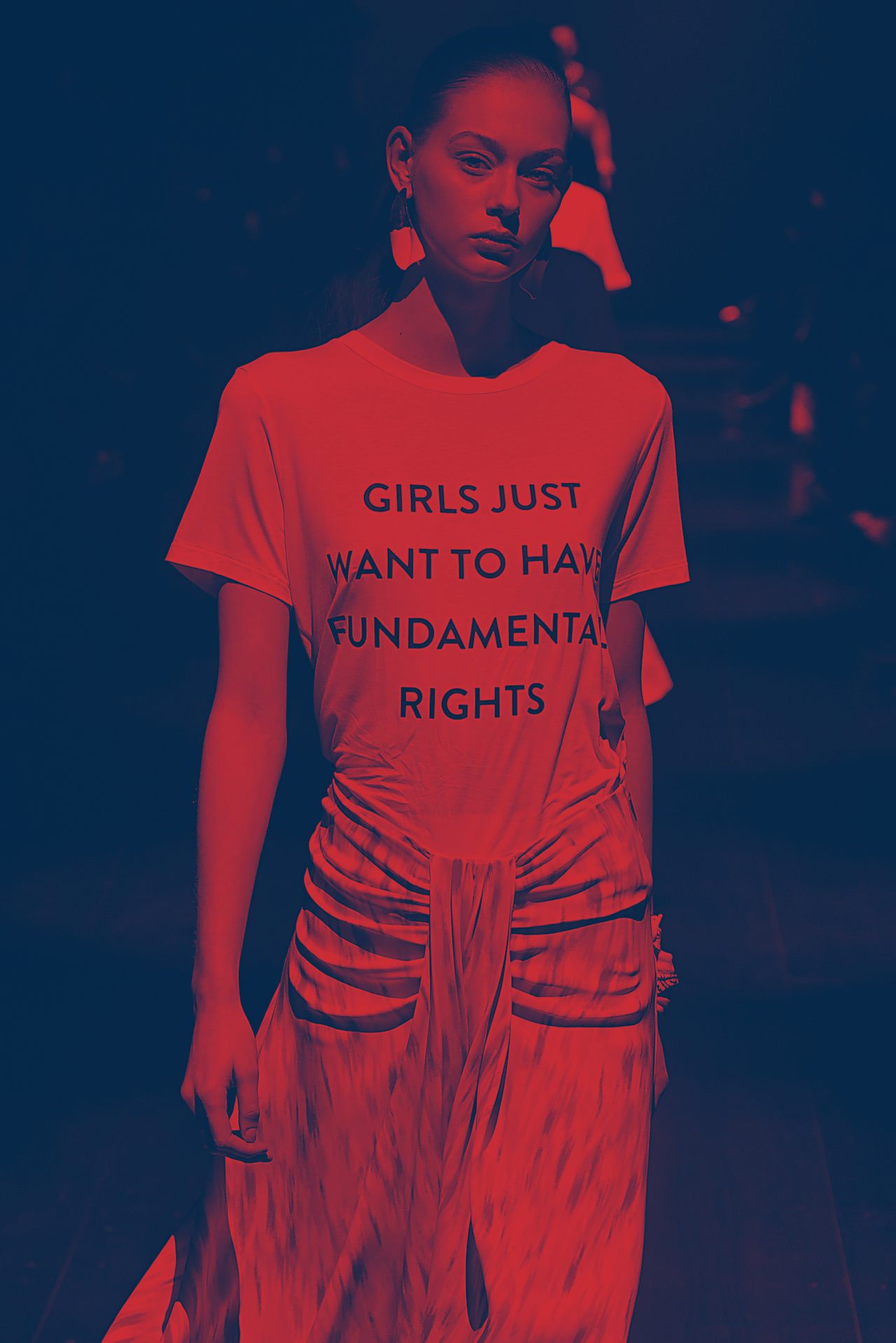

If you want to understand my politics, look no further than my dirty laundry. This isn’t a metaphor; nestled somewhere between grimy socks and distressed denim you’ll find an outfit for every rally: “LOVE IS LOVE” “HILLARY 2016” “I STAND WITH PLANNED PARENTHOOD” “THERE IS NO PLANET B,” and my favorite, “WOMEN OWE YOU NOTHING.”

But I can’t remember the last time I washed these shirts, let alone wore them. In the face of relentlessly bad news, I’m done wrestling with my dual convictions that everything must change and nothing will. I’ve traded in my progressive politics for a new identity: exhaustion.

By the looks of recent trends in T-shirts, I’m not alone. T-shirts featuring political and self-care-minded slogans, sold everywhere from Amazon to the finest boutiques, offer consumers the opportunity to wear fatigue on their sleeves. I’ve taken to calling this trend “ennui tees.” Such tees read more like exasperated texts to a roommate than meaningful political statements. “UGH, LIFE” ($10.79, Fairy Season) “MEH” ($17.49, spreadshirt) “NOPE” ($12.99, Target) they proclaim. And yet, they are everywhere: sported by spiritless baristas, defiant teenagers, soccer moms, resistance dads, and even celebrities.

“Who the hell would wear these in public?” I found myself asking whenever I saw someone wearing an ennui tee. Exasperated, I turned to my laptop for answers. But the more I plotted out the extensive family tree of T-shirts featuring disaffected one-liners, the more I understood that they betray a unique blend of lethargy and despair characteristic of an age in which we can’t afford to live in a world that is basically ending.

What can ennui tees tell us about the current condition? If it is true that, as a recent exhibition at the London Fashion and Textile Museum posited, slogan tees have always signaled “who we are and who we want to be”, are we just tired people who want a fucking break?

Putting words on clothing, of course, isn't new. The slogan T-shirt has existed for at least 50 years, enduring as a medium through which to express affiliations, brand loyalties, political positions, and cultural tastes. Popular accounts trace the style’s origins to a London shop called Mr. Freedom that was popular in the 1960s for its graphic tees featuring cartoon characters, and the trend evolved to include words in subsequent decades.

In the ‘70s, Vivienne Westwood boldly made the T-shirt into a medium for punk expressions by making shirts with the words like “chaos” “destroy” and “expose” on them. In 1984, when fashion designer Katherine Hamnett shook British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s hand while wearing an anti-nuclear slogan tee, political messages on clothing came into the mainstream. The humble article has remained a durable canvas for self-expression ever since, a staple of political campaigns and social movements.

Given the historical function of the slogan tee to align its wearer with a cause, ennui tees break from tradition by refusing to declare allegiance to anything at all. It seems our most noble cause is reclaiming naps ($10, Shein).

Ennui is a French term describing a gripping melancholy or listlessness caused by depression or boredom. In his 1998 analysis of ennui in European literature, Norbert Jonard argues that ennui is a recurrent phenomenon that shows up in moments of crisis or ideological change). Etymologically, the term connotes both hatred of the world and oneself. There’s not much that could show you hate yourself and the world more than wearing a t-shirt that says “everything sucks” or “I literally do not care.”

While the slogan tee historically served to identify friends and foes in public spaces by drawing an embodied line in the sand, ennui tees lack any discernible ideology (beyond tired refusal to engage). Their ambiguous object of disdain expands possibility of alliance, since the viewer can project their own frustrations onto them.

In this polarized political climate, with its record low trust in public institutions and widespread pessimism about the future, perhaps ennui tees signal a sort of desperate effort to find common ground by refusing to claim any ground at all. The most widely held and least politically divisive stance might just be despair.

There is something appealing about the incisive brevity of ennui tees. If you’re like me, current events have taken a toll on the sophistication of your political commentary. Compellingly crafted and meticulously researched Facebook updates will never change my Uncle Joe’s position on health care, so I limit my social media posts to a few choice expletives.

I’m not going to lie, It feels good. I’m done being articulately defiant; ennui tees allow me to be defiantly inarticulate. At an time when “SAD” passes for presidential commentary, “Yeah, No” is certainly eloquent enough for my slogan tee.

In the past, slogan tees largely served a pro-social purpose, providing a visual marker for membership in a tribe. But many ennui tees have the opposite goal: to signal that the wearer, in fact, hates other humans and wants nothing to do with them: “It’s too peopley outside” ($25.97, Amazon) “I like long walks away from everyone” ($29.50, Redbubble) “Ugh, people” ($20, TeePublic).

Perhaps the most banal revelation laid bare by ennui tees is capitalism’s tendency to colonize every inch of human experience, including — and most dangerously — our nihilism. The economic system at the root of our “ughs” “nopes” and “everything sucks” — the machine driving income inequality, overwork, pollution, climate change — is that same one that provides a soft, fitted size medium way to say “fuck you.” This is the eternal truth of all slogan tees, no matter if they protest nuclear energy, beg passersby to Make American Great Again or declare that Love is Love: our hate, hope, and yes, even ennui is imminently marketable, and we are too tired to resist it.