Just over a month ago, The Guardian ran an article commemorating the 30th anniversary of Roald Dahl’s classic children’s novel Matilda which, in case you don’t know, is about a precocious five-year-old who uses her powers of telekinesis to escape her neglectful parents and get her sadistic headteacher fired.

The article featured six children’s authors, all sketching their suggestions for what Matilda herself would be up to now, at age 30 (before you ask: (1) she loses her powers at the end of the book, so no she wouldn’t just obviously be doing magic shows, or working for the military; (2) yes, I do realize she would be 35 now not 30 but this is The Guardian’s mistake, not mine). The proposed futures ranged from Matilda becoming a stand-up comedian; to finding success as an author; even to becoming the prime minister (in this version, Matilda apparently came to power in a sort of anti-Brexit coup). But the fact is, none of these futures rang even remotely true. We all know what happens to sensitive, precocious millennials like Matilda: they end up suffering from Gifted-Kid Burnout.

Matilda will never be the prime minister; for that matter, Lisa Simpson will never be the president either. Under present conditions, these characters would be lucky not to spend most days huddled under their weighted blankets, scrolling dead-eyed through social media, neglecting to reply to emails from their PhD supervisor or their parents or their boss. Matilda will never be prime minister; Lisa Simpson will never be president. But they will both have an expertly curated folder of depression memes.

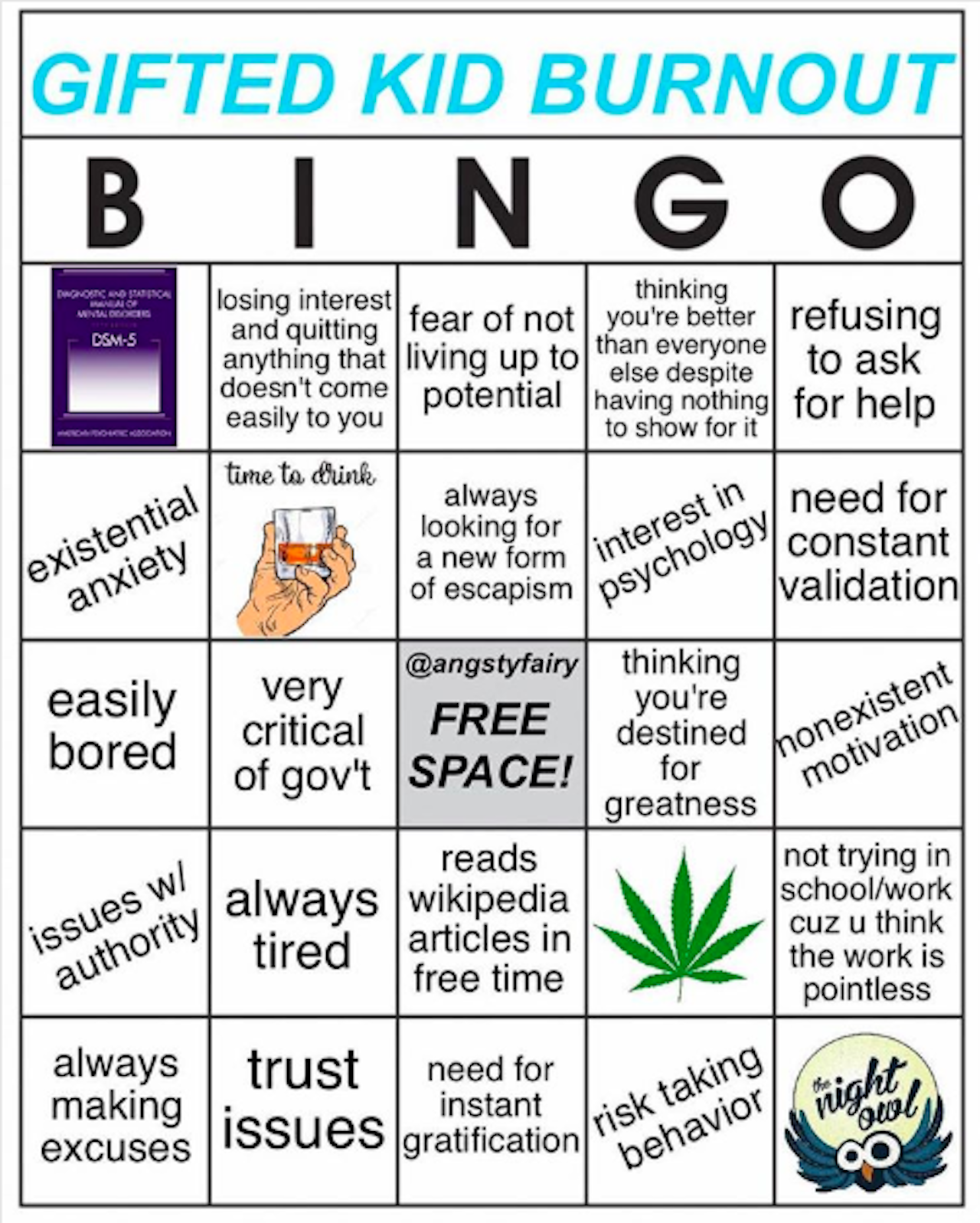

“Gifted-Kid Burnout” as a phenomenon is a bit hard to categorize: it falls somewhere between a meme and a personal identity. As far as I can tell, the current usage of the phrase can be traced to the posting of the Gifted Kid Burnout Bingo chart on Instagram by @angstyfairy in July 2017. This chart was then widely shared — often by people who felt “personally attacked” (that is, in some way accurately described and thus validated) by it. But of course, the very fact the chart was able to go viral indicates that the identity pre-existed the phrase (and I’m sure most people reading this will remember encountering it, or indeed embodying it, before mid-2017). The Gifted Kid Burnout Bingo chart is just one of those things around which such an identity can crystallize.

As the Bingo chart’s various categories suggest, the burnt-out gifted kid is someone who has been paralyzed by their own potential. As a child, the burnt-out gifted kid found everything easy, was praised constantly by their elders for their abilities; they were assumed to be, and assumed themselves to be, destined for great things — professorships, executive jobs, prestigious literary awards. But then something happened — a few bad grades; the realization, at college or grad school, that no one seems quite so exceptional when they’re surrounded by other high-achieving people; the sudden need to work hard at something to master it... and the burnt-out gifted kid failed to adapt, dropped out; they were done. Now they live out their days in a depressive haze, propped up in bed or struggling to get up in time to start work at the sort of dead-end job that, growing up, they assumed was below them, that they’d never have to do.

Some people, as I’ve said, really identify with this — the comments on @angstyfairy’s original Instagram post are predominantly along the lines of “my existence summed up in 25 statements” or “i’m shaking cause this is fucking me.” But others really hate it.

Hey guess what nerds, getting good grades in 4th grade math and getting to do some Gifted Program projects doesnt mean you were a child genius. If everyone is a "burnout bright kid" then nobody was. Youre just a lazy 20 something with good parents who made you do homework.

— Timothy (庭夢) (@LiterallyHell) November 12, 2018

This is also not "gifted kid burnout" it's "slightly above avg intelligence upper middle class child being forced to live in the real world for the first time as a 23 year old bingo"

— Brendan (@ninthhostage) November 12, 2018

i hate gifted kid memes omg let it gooo use some of them internal validation skills or idk pay a bill truly no one is exceptional, you fuckin nerds

— im rebranding (@stillrebranding) August 27, 2018

For these people, “Gifted-Kid Burnout” is just an excuse, a way of failing to come to terms with the fact that you’re failing, not because you were too talented — you never were — but because you’re too lazy to cope in a world that doesn’t share the good intentions your parents, and maybe some teachers, held towards you when you were growing up. The “burnt-out gifted kid” is really just someone who needs to start working harder: they can thrive, but only once they embrace the fact that they’re no better than anyone else is.

I think I’m in a position to take a somewhat objective view of the Gifted-Kid Burnout meme. I didn’t show any particular promise as a kid, and I haven’t failed especially egregiously as an adult: My life isn’t a tragedy of unfulfilled potential — thus far, it’s been a mostly tolerable procession of various ruts and lulls. Equally, because I’ve got where I am today primarily through dumb luck and doing my own thing (as opposed to working hard to succeed on someone else’s terms), I’m not inclined to fetishize graft. From my sensible, centrist position on the Gifted-Kid Burnout meme, I feel like I want to say: on this issue, if no other, both sides have a point.

On the one hand, there is real suffering encoded in the Gifted-Kid Burnout meme. A lot of people who relate to it because their lives really haven’t turned out like they imagined they would, and they’re struggling as a result (consider for instance this recent contribution to The Outline’s very own “Ask A Fuck-Up” column). Gifted-Kid Burnout can provide people with a good narrative explanation as to why this should be: your life hasn't turned out the way you wanted it to because, as a child, your exceptional gifts meant that no one bothered inculcating in you the key skills and psychological coping strategies that, it turns out, real people need in order to thrive as adults in the real, adult world.

This may well be true — at least in part. But then the problem is, that the Gifted-Kid Burnout explanation doesn’t seem like it can provide us with all that much more than a sort of comfort blanket of sadness. I don’t think people who identify with the meme are just being lazy, and need to be taught the meaning of hard work — unless of course we understand “the meaning of hard work” here to be that hard work sucks and people should be liberated from it. But equally, I’m not convinced that the real, dominant, ultimate explanation as to why your life hasn’t turned out how you want it to, has to do with what you were like in grade school.

The other day, I came across this piece by Mark Fisher — an extract from k-punk, the forthcoming posthumous collection of his writings. This piece pointed me to a blog post from 2014 by something called the Institute for Precarious Consciousness. In this piece, the Institute argues that every phase of capitalism has a “dominant affect”: a dominant emotional orientation, which functions in part as a way of controlling people — although it is also, the authors claim, a pole around which resistance to the established order can coalesce. Once, this dominant affect was misery; until around 40 years ago it was boredom. But nowadays, in the age of neoliberal capitalism, the dominant affect is anxiety.

“Today’s public secret is that everyone is anxious. Anxiety has spread from its previous localised locations (such as sexuality) to the whole of the social field. All forms of intensity, self-expression, emotional connection, immediacy, and enjoyment are now laced with anxiety. It has become the linchpin of subordination.”

In both work and leisure, we are under constant surveillance: the smallest shortfalls, the smallest infractions, will be logged by our managers, screengrabbed as “receipts” by our followers on social media. We worry, rightly or wrongly, that even one mistake, improperly navigated, could cost us our job and all our friends. We worry that even this anxiety might be an indicator of guilt.

We want desperately to do something about this, but the logic of this system is so overwhelming we can’t see any way of doing things differently. The only things we can think of, through which we might take control of our lives, involve more surveillance, more micromanagement. “Parental management techniques, for example, are advertised as ways to reduce parents’ anxiety by providing a definite script they can follow. On a wider, social level, latent anxieties arising from precarity fuel obsessive projects of social regulation and social control. This latent anxiety is increasingly projected onto minorities.”

These problems have been compounded by the effects of the financial crisis of 2007 and 2008. Certainly surveillance and micromanagement were an increasingly prominent part of everyday life even before then — from Supernanny to the War on Terror. But there was, back then, still a sense that if you kept your head down and submitted to all of society’s various anxiety-generating rituals, your life really could improve (I remember filling out all sorts of pointless charts at school which were supposed to chart my progress towards various learning goals, towards doing things like applying to university… did students of previous generations do anything like this? Thinking about them now, they resemble nothing so much as — indeed, are a bit confused in my mind with — the little log book I had to fill out charting what jobs I’d applied for every week, when I was claiming unemployment benefit).

But then suddenly, at around the time that I – and, I’m guessing, a lot of people who identify with the Gifted-Kid Burnout meme – started university, all the old opportunities there used to be to get on in the world, to secure a good and hopefully non-precarious job, to fulfil all your parents’ expectations of you... just, sort of... disappeared. And no matter how much you, or anyone else, kept on surveilling, kept on micromanaging, they still haven’t come back. Now all we have left is the anxiety: the endless, painful side-effect of a ritual which has long since ceased to have any even coincidentally beneficial effects.

It strikes me that this constitutes a much better explanation for what is really behind Gifted-Kid Burnout. This is why so many people feel they used to be on the right track as a kid, but aren’t now. You haven’t failed because your preternatural brilliance meant you never had to learn hard graft — you’re failing because the world simply hasn’t provided you with the opportunities you would have needed to flourish. All it has given you — all it is interested, really, in giving you — is the yawning vertigo of anxiety. But unfortunately — and this is where, I’m afraid, the people who hate the Gifted-Kid Burnout meme really do have a point — wallowing in whatever sadness you have about how your life has turned out probably won’t help.

Probably my favourite line in The Communist Manifesto is the one where Marx and Engels say that under capitalism, the past dominates the present; in Communist society by contrast, the present will dominate the past. We can’t let our own pasts, or even just our images of them, continue to dominate our horrible, anxiety-ridden presents. This can’t possibly be easy, especially given how determined the world seems to be to break us. But regardless of how much you might feel like you’ve betrayed the promise you once seemed to exhibit as a child, everyone needs to find ways of taking action, to change the way the economy is organized and through this break the grip anxiety seems to have over all our consciousnesses today. Which is all to say: radicalize the gifted kids.