The New York City subway system, which every day suspends millions of irritated commuters in a purgatory without consistent smartphone service, is a great place to advertise. There are spots for delivery groceries, delivery dinners, delivery mattresses — the colors bright, the copy flip and shameless. We don’t feel great, the ads suggest, but we might feel better if someone else did our chores and another person brought us dinner.

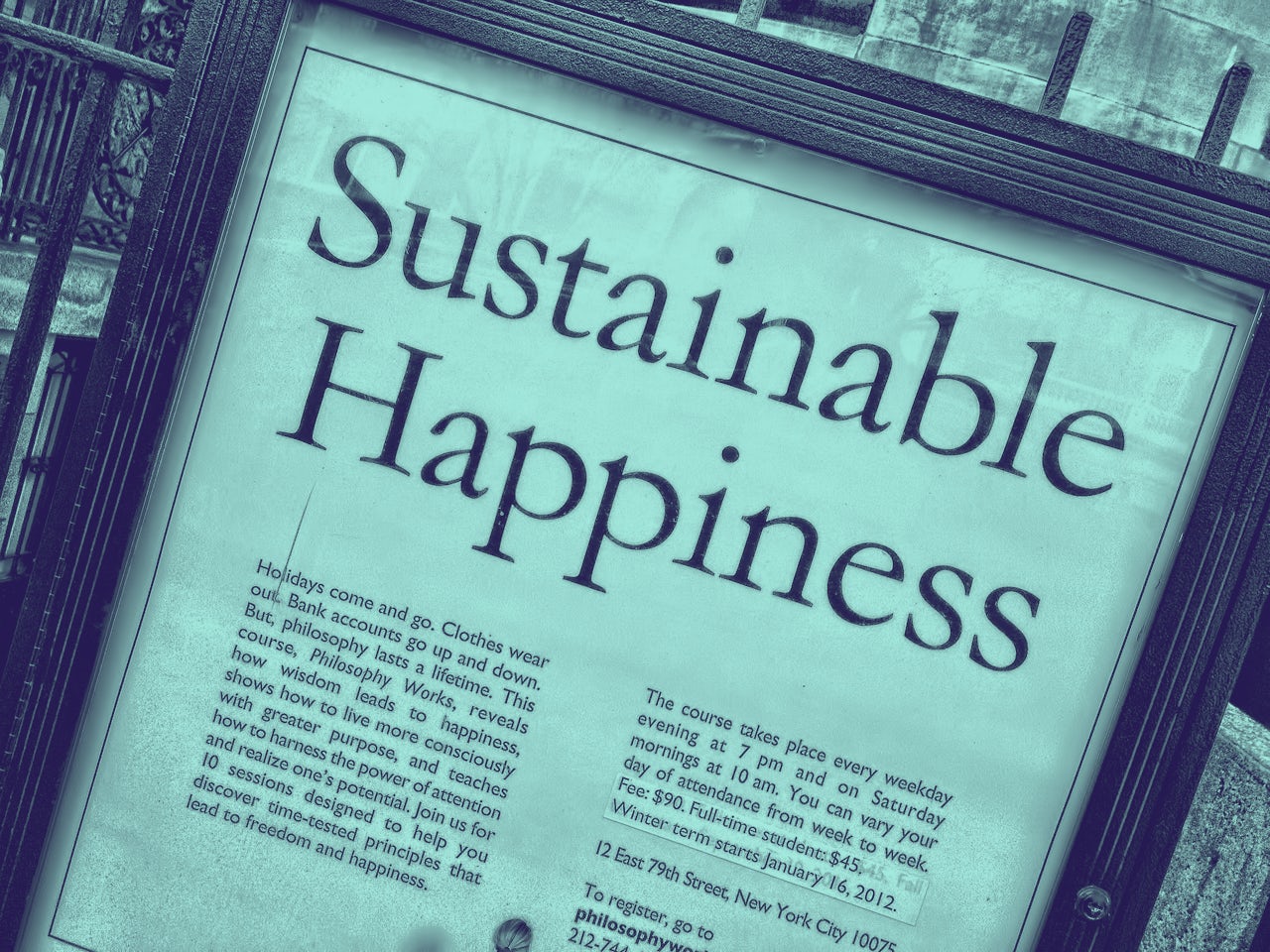

But one long-running ad has always stood apart. We see a woman from the back. She holds her purse behind her and gazes up at two enormous words: “SUSTAINABLE HAPPINESS.” The fine print reads: “Jobs come and go. Physical beauty fades, markets rise and fall. Even close relationships can end. But the benefits of philosophy last a lifetime.” These benefits — HAPPINESS included — can be gained, according to the ad, by attending the 10-week introductory course at a place called the School of Practical Philosophy.

The ads caught my eye when I first moved to New York because I had an undergraduate degree in philosophy, and because I was frequently miserable. On the SPP’s website, I learned that it was a nonprofit school for adults, and that the introductory course, “Philosophy Works,” offered “wisdom from the East and West” and was intended for those who were “sincerely interested in self-discovery.” In a series of video testimonials, students said things like “It’s been incredibly liberating” and “I have gone through a tremendous transformation.”

By the 2016 election, I found the ads newly convincing. For months I’d been having a persistent, intrusive little daydream, in which I drilled a golf ball-sized hole in my skull and upended a gallon of bleach into it. It wasn’t that I wanted to become inert and skip every difficult conversation, but some corner of my brain begged for quiet. Maybe the SPP could help. I signed up for the ten-week introductory course, which cost $10.

The spring semester began on a chilly evening in April. I assumed we’d meet in a borrowed CUNY classroom or a rented coworking space, but my phone led me to a seven-story mansion on 79th St. between Madison and Fifth Avenues. I arrived early, circled the block, and looked up the property online. The building, purchased by the SPP in 1975, was now worth an estimated $41 million. Your generic ultra-rich person is unsettling enough, but there was something even worse about a philosophy maybe-cult with access to vast sums of capital. I shared my location with a friend just in case.

The first thing I saw when I heaved open the mansion’s heavy wooden door was a large golden sculpture of a woman in a flowing gown, her eyes half shut, one hand extended in a beatific gesture. Behind her were two loincloth-clad men standing in a garden, one holding the Staff of Hermes and the other strumming a lyre. The golden woman, according to the SPP, is Philosophy personified. In the foyer a flock of efficient business-casual types, mostly men in late middle age, checked names on their clipboards and directed me and around 30-odd other hesitant-seeming newbies, to a classroom on the building’s third floor, where we settled into rows of uncomfortable chairs. No one spoke.

A middle-aged woman with fuzzy blonde curls awaited us at the front of the room. Her name was Amy, and she was our leader. She had a Long Island accent, and wore a turtleneck, bootcut slacks, and several long strands of beads around her neck. She and her husband had been attending the school for years, she said. She was still a student, just like us, and she wasn’t paid to teach; like nearly everyone involved at the school, she was an eager volunteer.

One of my classmates, a man in his fifties, interrupted her. I had noticed him on the way in because he was wearing a big silver watch on each wrist. “Phil-ahhhh-sohh-phee,” he said, turning to gaze serenely around the room. “That means study of man.”

“Well, that’s a nice little ditty,” said Amy. “But no.” She explained that the word’s Greek roots, philo- and -sophos, combined to mean love of wisdom. She seemed tremendously excited for all of us to be there, and like she expected to be interrupted many more times.

We broke into groups and shared our reasons for attending. My group consisted of Two-Watch Guy and a catalog-handsome man in a Lake Tahoe T-shirt. Two Watch Guy volunteered to share first. He smiled at us and exclaimed, with a little fist pump, “Happiness!” He did not elaborate. Tahoe, who I guessed was a recent transplant from Colorado or Utah but had in fact immigrated from Northern Ireland, was looking for a new spiritual practice after rejecting the Catholic Church in his youth. I stammered something about wanting to further my undergraduate studies.

After the entire class reconvened, a few volunteers shared their answers with the room. With the exception of a few showboaters (a 20-something with a handlebar mustache said he wanted to “get to the bottom of [his] psychological machinery”), most people were there because of the subway ads. They wanted HAPPINESS, and they wanted it for the price of a weekday matinee.

Amy asked us to brainstorm the qualities of a wise person and recorded our answers on a whiteboard. “Caring,” said an ER nurse. “Experienced,” said a lawyer. “I don’t know how to put it into words, but the ability to walk in someone else’s shoes,” said Two-Watch Guy.

These were great, Amy said. But she had a secret for us: wisdom was an innate human trait, and we were all wise. “Even babies know they shouldn’t touch a hot stove,” she said. Some hands went up, but she continued.

Were we skeptical? No matter — Amy was going to show us our wisdom, by way of a valuable philosophical exercise. We were to close our eyes and to think of a personal quandary, something that had us really stumped. Well, fine, I thought — most things in life had me stumped. I picked something concrete. I’d been debating putting a deposit down on a little bare-bones studio apartment, which would mean moving out of the beloved four-bedroom I shared with good friends. I had to decide soon, or someone else would sign the lease.

“Now,” said Amy, “ask yourself: what would a wise man or woman do?”

I waited for more, but that was it, the whole trick. I almost laughed. If I knew what a wise person would do, there would be no dilemma to resolve. Where would a wise person choose to live? Probably not in New York City. When Amy told us to open our eyes, Tahoe and I exchanged stupefied glances.

But the reception was enthusiastic. The man to my left was eager to share. He was fiftyish, large, bald, and friendly looking, and he had piled two iPhones on the empty seat between us. “You really burst my bubble,” he told Amy, with a sort of cheerful, faux disappointment. He had been planning to buy a TV for his bedroom, one of those truly immense ones. His daughter objected — they already had a huge flatscreen in the living room — but he didn’t care. He had to have it.

Now, though, he was reconsidering. A wise man wouldn’t purchase something he didn’t need. “Very good,” said Amy.

We talked more about wisdom. Amy read a quote she attributed to Einstein — “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler” — and the class murmured in comprehension and approval. (The quote is apocryphal.) We took a break and headed to the basement, where volunteers sold coffee and bowls of vegetarian soup. The more advanced students, already seated at the communal tables, smiled at us knowingly, like we were newlyweds about to depart on one big honeymoon. Then we shuttled back upstairs, learned a short guided meditation practice, and were finally dismissed.

Tahoe and I walked to the subway together. The class was ridiculous, we agreed, and a waste of time. We had sat in that room for two-and-a-half hours and learned nothing, besides some mediocre anecdotes about strangers. I didn’t expect to see him again.

With its total lack of rigor and focus on feeling good, the SPP struck me as a distinctly American institution. In fact, it’s the American branch of a British organization, the School of Economic Science (SES). According to Peter Hounam and Andrew Hogg, two London Evening Standard reporters who published a book about the SES in 1985, it began in 1937 as a humble economics study group. Andrew MacLaren, its founder, was obsessed with taxing land ownership as a form of wealth redistribution, and the SES was a group for studying and advancing that agenda.

Then, in the ‘50s, MacLaren’s son Leon took over. Leon was a proponent of the land tax, too, but came to believe that the very nature of mankind needed to change before any economic wrongs could be righted. He began studying the teachings of two mystics, George Gurdjieff and P. D. Ouspensky, who believed they possessed the key to immortality, and later fell in with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, primarily known in the West as guru to the Beatles. In its written materials, and in class, both the SES and the SPP claims Leon as the sole founder; the elder MacLaren is omitted entirely. With Leon at the helm, the SES shifted in focus, demanding a new level of dedication from its students. Things took a dark turn, hence why Hounan and Hogg’s book is titled Secret Cult.

Hounam and Hogg interviewed more than 50 former SES members while researching Secret Cult. Their stories are damning. One student described the school’s insistence that she see only SES doctors during a difficult pregnancy; when she finally made it to a hospital, the doctors were horrified by her condition, and her baby died shortly after birth. Others tell about the breakups of their marriages, and many discuss attempts made by the school to isolate students from their unaffiliated loved ones. Leon MacLaren died in 1994, and the SES claims to have made significant changes, but its reputation hasn’t fully recovered. Children who grew up in the SES have written op-eds and novels about the organization’s horrible legacy.

I was relieved to see Tahoe when I showed up for the second class, the theme of which was “awareness.” Philosophy, Amy said, was designed to raise us from “waking sleep,” our default state, to something called “higher consciousness.” One way to wake up, she said, was to ask ourselves what a wise man or woman would do — a panacea, apparently. My classmates gamely shared anecdotes about moments in which they hadn’t been adequately aware. Only Tahoe seemed aggrieved. He sat next to me, vaping furiously into his jacket sleeve.

During the mid-class break, we went outside so he could Juul freely. He told me he wasn’t sure why he’d come back; he found Amy patronizing and dull. I told him that she appealed to me, in a way. She seemed well-intentioned, guileless, not capable of manipulating anyone even if she tried. But we agreed that she could not be taken seriously. Listening to her answer questions was like listening to an underprepared high-schooler bullshit during a class presentation. (“Does each person have the same amount of wisdom?” Two-Watch Guy asked that week. “No, we all have different amounts, but together we form a whole,” said Amy, and quickly called on someone else.) Mostly, though, Amy stuck to a script. The “powers that be,” she said, demanded that certain ideas be read verbatim.

Debate was discouraged. One week, Amy explained to us that anger was a useless emotion, one that led only to “endless ignorance and suffering.” I asked about righteous anger, the kind that sometimes sparks social change. An older woman with big pearl earrings chimed in, defending another kind of rage: “What about when a van is double parked outside Gristedes, and cabs can’t get by?” (I laughed, but my classmates seemed to take double parking very seriously.)

There was beauty in everything, we learned one week, a banal-seeming claim that set off an agonizing half-hour argument about whether there was beauty in the Holocaust.

In response, Amy invoked one of the principle tenets of the SPP. “You should neither accept nor reject the material,” she said. Instead, we should try it out, and see how the ideas worked in our own lives. It was a clever maneuver for controlling the skeptics, as it meant we couldn’t evaluate the material until we’d left the classroom.

The classes had more in common with my Catholic K-12 education than with the philosophy courses I took in college. It’s difficult to characterize what we learned, because none of it really cohered. Each week had a theme (“The Light of Reason,” “Beauty,” etc.), and consisted of cherry-picked ideas from eastern and western philosophies and religions, devoid of context and presented as fact. We had souls, we were told; the proof was that our bodies and thoughts and feelings changed, but something inside of us remained constant. There was beauty in everything, we learned one week, a banal-seeming claim that set off an agonizing half-hour argument about whether there was beauty in the Holocaust. Sometimes we discussed a quote from Rumi or Shakespeare or another famous man.

We were actively discouraged from taking notes (“There’s no need,” said Amy repeatedly, eyeing me with suspicion as I scribbled in my notebook), and we read nothing. Trump had been sworn in just a few months earlier, but in class there was no mention of politics, no talk about what a person might owe her community beyond the neutral commandment that your word should be your bond. Suffering was to be dealt with on an individual scale.

There was something surreal about leaving work on Thursday evening and taking the subway to a mansion where I would be told a bunch of weird lies. Each week, the class shrank. Tahoe, my only kindred spirit, left in the middle of class during the third week, and didn’t show up on the fourth.

I read Secret Cult midway through the course. It was hard to square its horror stories with the SPP, which, like a lot of Americanized British things, wasn’t quite as compelling as the original. The longtime students I met seemed to have functional home lives and decent careers. Amy had a teenage daughter with no interest in attending, and while Amy clearly wished she would, it didn’t seem to be the cause of a family rift. As far as I could tell, most of the unpaid volunteer work was restricted to teaching, or cleaning, or making the sizable, expensive-looking flower arrangements that adorned each classroom. I found some Reddit forums of former SPP members, but most people said they had stopped attending because the classes were, to quote one commenter, “dead bloody boring!”

While it seemed strange to me that the SPP had so much money to spend on subway ads and mansion upkeep, their tax filings cleared up that particular line of suspicion: They just have incredibly low overhead. Amy and the other teachers are unpaid, students perform custodial work, and the SPP owns its own building. (A guest tutor once casually said that a group of students had mortgaged their own homes to buy the mansion, but the SPP would neither confirm nor deny this claim.) In 2017, the SPP received about $240,000 in grants and donations, and made around $750,000 from classes, workshops, retreats, and the sale of books and concessions. Later courses (on topics like “Love,” “Freedom,” “Different levels of knowledge,” and “How actions regulate our lives”) are more expensive than Philosophy Works, but there’s no class listed on the website pricier than $345; most are $90.

Some students in the higher ranks almost certainly spend thousands a year on the school, but the SPP doesn’t seem like a Scientology-style extortion racket. New York is full of rich people doing bizarre things with their money; a full year of upper echelon classes is likely no more expensive than an Equinox membership,. And while I couldn’t fathom spending my Saturday mornings cleaning a mansion for free, it struck me as no less fun than joining an adult kickball league.

Maybe the SPP felt unthreatening because of Amy, who seemed particularly inept at indoctrinating the vulnerable. By the final weeks, attendance had dwindled so much that we had to combine with another intro class. But the people who remained seemed sincerely invested. I bumped into Tahoe during break one night, chatting on the stoop with another youngish brunette. He hadn’t quit after all; he’d just switched into another section. His problem was indeed with Amy, not the material. He had also replaced me with a less-cynical philosophy friend, and they were planning to take the second class, another course on happiness, together. It depressed me that Tahoe and so many other competent-seeming adults — schoolteachers, social workers, corporate lawyers — took the SPP so seriously. It was a little like learning your primary-care doctor was a flat-earther.

#kindness#awareness#happiness#smile#innocence#truth#honesty#philosophy#attention#mindfulnesspic.twitter.com/lqaQtvGoZt

— Practical Philosophy (@PracticalPhilo) March 29, 2018

Our last class felt like high school graduation; there was an air of festive camaraderie. At the break, the remaining students passed around a notebook to make an impromptu class directory. Unwilling to add my number, and feeling negative and mean, I slipped outside.

Two-Watch Guy, friend to all, joined me on the stoop. We sat and watched the cabs drive by. I figured I wouldn’t see him again, so I asked him a question: “Why two watches?”

He lifted his wrists for me to examine. What I had taken for a second watch was really a notched silver band. It was a bracelet, he told me, a gift from his sister, intended to help him heal from a divorce that had broken his heart; he had worn his wedding band for seven months after the divorce papers were finalized.

“Because it was stuck?” I asked, “Or because it was hard to take off?”

“Both,” he said, and we laughed.

Here’s what else I learned. Two Watches looked forward to class all week. His divorce had been awful, his kids lived with their mom, and he was lonely. (“Even close relationships can end,” goes one of the SPP’s subway ads.) He worked in maintenance at Yankee Stadium. He hadn’t gone to college, and he didn’t belong to a church — his life was not teeming with opportunities to talk about the nature of wisdom. The lessons were fun, but the real appeal was community.

The students who stuck around until the final week reminded me of the many lonely people I had met while working in the service industry, people who often tried to turn a short, professional interaction into something lengthy and intimate. It was possible my classmates were not compelled by the notion that “three distinct energies governed the universe.” Maybe they just liked sitting in a room of people who would listen to them. The week before, an elderly widow had confessed in halting speech that it was hard to be kind to her husband towards the end of his life, because his illness changed his personality, made him mean. I watched as the woman sitting next to her, a stranger, squeezed her hand.

Midway through Philosophy Works, I signed a lease for the studio. I attended class the night before the move, and realized during the break that that a wise person would bail and finish packing.

I told Amy I was leaving and apologized. I didn’t mean to be disruptive; I probably shouldn’t have come at all.

“No, no,” she said, “it’s good you came.” She gave my shoulder a little squeeze. “This is the important stuff.”