I was 12 when I first swore off religion. My friends and I loitered outside a musky wooden confessional comparing penances assigned by our sour-breathed priest. One girl stole hoop earrings from Dillard’s: that meant 10 Hail Marys. A boy drank alcohol under the stadium bleachers: 50 Our Fathers. Somehow, I — an inveterate goody-two-shoes — received the heaviest sentence: 100 Hail Marys and 500 Our Fathers.

My sin? I doubted the existence of “God.”

This solidified my identity as a preteen apostate. Despite the overwhelming spiritual consensus within my small Texas town, I knew “God” didn’t exist.

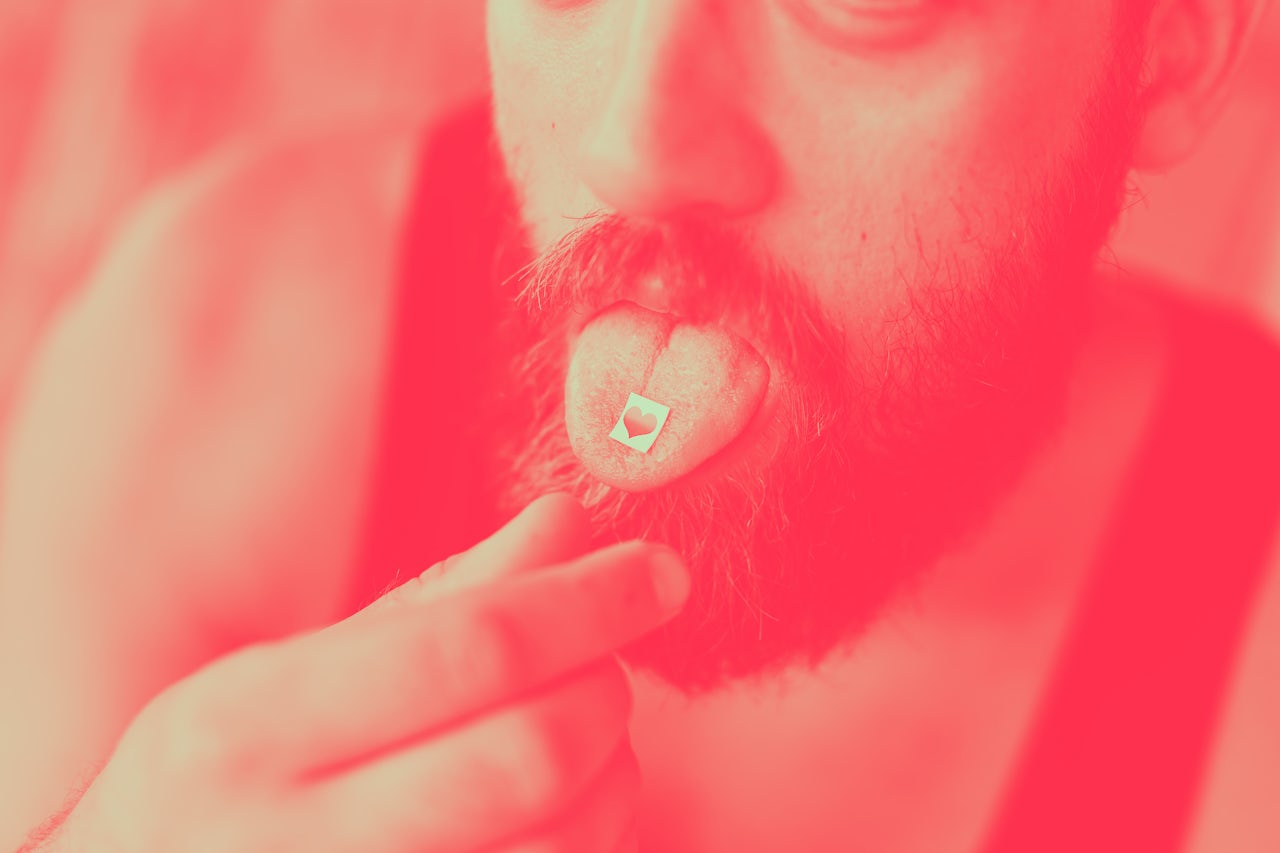

Nothing shook this conviction until I participated in a clinical trial at Johns Hopkins University last year in which I was given high doses of psilocybin — the psychedelic compound in “magic mushrooms” — to treat major depressive disorder.

A long journey brought me to Johns Hopkins. For 16 years, I wrestled with an insidious darkness. When my parents took me to the doctor as a child, he assured them: depression is not a crisis, it’s an equation. Medications would balance my imbalanced brain. Combinations were tested, doses increased. Weekly therapy marked the passing of years. Things worked until they didn’t. Enduring side effects that ranged from the annoying (excessive sweating) to devastating (weight gain), I managed periods of productivity, friendship, and even joy. But every good moment drooped under the weight of a question: when would darkness descend again?

Major depressive disorder is a complex biopsychosocial illness, one for which we desperately need better treatments. Depression affects more than 16.1 million American adults, roughly 6.7 percent of the population, and is the leading cause of disability in the U.S. The most common depression medications, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), were developed 30 years ago. While they are effective for many, they can take weeks to months to kick in, and many people find the side effects intolerable.

The FDA recently approved a nasal spray form of esketamine, a drug that shows promise for short-term, rapid depression relief. While there is excitement about psilocybin’s potential to have longer-lasting effects for the depressed, more data is needed. Clinical trials using psilocybin to treat depression, addiction, Alzheimer’s, and end-of-life anxiety are ongoing at Johns Hopkins, Imperial College London, New York University, and other institutions.

Every good moment in my life drooped under the weight of a question: when would darkness descend again?

Having seen headlines about the promise of psychedelics research, I didn’t think too hard about enrolling when my best friend, who studies at Johns Hopkins Medical School, told me that a psilocybin study sought volunteers. Traveling from my home in D.C. to Baltimore across a number of weeks, I completed countless interviews, mental-health histories, surveys, cognitive tests, an electrocardiogram, and a physical exam to determine if I qualified. When I finally brought home a 15-page release form that detailed the study requirements (highly structured preparation meetings, closely monitored psilocybin sessions, and follow-up appointments), my boyfriend at the time read it and laughed, “This is the ONLY way you would ever trip.”

This was true. I had been too risk-averse to try illegal drugs; I did not want to give free reign to a mind I’d come to regard as a saboteur and traitor. The structured trial environment minimized risks: I completed a series of preparation sessions where I grew to know and trust my two experienced “guides” and established intentions for the sessions. The guides would monitor my every move and help me navigate any difficulties — such as intense fear or anxiety — that might arise while on psilocybin.

So I felt safe as I laid down on a big comfy couch in Baltimore on two occasions and ingested high doses of laboratory-synthesized psilocybin. What I didn’t know — having chosen not to influence my trips by reading literature on how psilocybin works — was that the same chemical being tested to treat my depression might also subject me to what a religiously inclined person might label “God.”

In case you missed it, we are in the middle of a psychedelic renaissance, marked most notably by Michael Pollan’s sweeping 2018 book How to Change Your Mind. Regardless, legacy stigma around psychedelics remains, even in the context of clinical trials. That’s partially why I don’t tell many people what I experienced during the clinical trial. But mostly it’s because the journeys were profound, deeply personal, and filled with insights that evade simple description. People who haven’t done psychedelics don’t get it; and often even people who have done them for fun don’t get it. The reaction is always the same: “You tripped for science. So what?”

Like all trip stories, mine sound crazy at worst and clichéd at best. But I can tell you this much: at the peak of my experience, my sense of self dissolved and I unified with an abiding force that permeated all existence — something that felt conscious, vast, benevolent, eternal, peaceful, and furiously important. After sitting up on the couch six hours later, covered in snot and tears, I struggled to put words to an encounter that felt more real than everyday reality — a mind-bendy paradox characteristic of many mystical experiences.

Encountering what I feel most comfortable calling “Ultimate Reality” during an experimental depression trial sometimes feels like a profound spiritual bait-and-switch. Why couldn’t they just treat my illness without screwing with my worldview? But exploding one’s worldview is the whole point of these treatments; in fact, the trial protocol — the doses, a welcoming environment, guides, preparation, laying down with eyeshades while listening to a carefully-selected musical playlist — is optimized to increase the likelihood of profound experiences.

At the peak of my experience, my sense of self dissolved and I unified with an abiding force that permeated all existence.

This is not because researchers want to change volunteers’ spiritual leanings. It’s because preliminary studies indicate that the stronger the transcendent experience, the more people overcome depression, addiction, fear of death, and report positive changes in behavior and attitude. No one really knows why, and more work remains to understand these experiences, their neurobiological underpinnings, and the mechanisms by which they improve people’s sense of meaning, purpose, and values.

And with psilocybin fast-tracked by the Food and Drug Administration as possible development into depression treatment as soon as 2021, more people may soon encounter something they interpret as “God” or “Ultimate Reality.” In choosing this treatment, I wonder if patients will grasp they could be choosing an entirely new ontology.

After my encounters, I developed a tempered fascination with the fact that a chemical compound could occasion a sense of unity so sublime as to reorient my worldview. Did my childhood priest feel the same way when he convened with God? Did Saint Teresa experience the same thing in the 16th century as I did tripping for science in 2018?

Ever since Timothy Leary’s LSD-laden days at Harvard in the ‘60s, countless philosophers, neuroscientists, psychonauts, and theologians have debated the commensurability of drug- and non-drug-related mystical experiences on largely theoretical grounds. A whole new subfield, neurotheology, has arisen to map spiritual and religious experiences onto specific brain functions. Researchers are beginning to apply rigorous methods to analyze post-experience accounts, and are even crowdsourcing reports of self-transcendence in the name of research.

And a new paper published in the journal PLOSOne is the first large-sample study to systematically compare natral and drug-occasioned encounters with what respondents call “God.”

Johns Hopkins researchers surveyed 4,285 individuals who claim to have encountered “God (e.g., the God of your understanding), Higher Power, or Ultimate Reality,” comparing key aspects of the experience, whether it occurred “naturally” or after taking psychedelic drugs. The researchers found striking similarities between the descriptions and personal effect of these encounters, regardless of if they, say, occurred spontaneously to someone in a church pew or during an ayahuasca ceremony in the Amazon.

A whole new scientific subfield, neurotheology, has arisen to map spiritual and religious experiences onto specific brain functions.

While the non-drug group was more likely to label what they encountered “God,” and psychedelic users “Ultimate Reality,” both characterized the experience in many similar ways.

“Really what the two groups call it is just semantics,” said lead author Roland Griffiths, a professor in the departments of psychiatry and neuroscience at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “The astonishing piece is that participants — whether they label their encounter God, emissary of god, or Ultimate Reality — use the same descriptors: it’s conscious, benevolent, intelligent, sacred, eternal, and all-knowing.”

David Yaden, a research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania unaffiliated with the study, said “if psychedelically triggered experiences are, in fact, subjectively similar to [other] religious, spiritual, or mystical experiences, then psychedelic substances provide a means to study these experiences in controlled laboratory settings. This is an important step towards scientifically understanding these profound and often impactful human experiences.”

But some, like Steve Katz, a professor of Jewish and Holocaust Studies at Boston University, are unimpressed. He worries characteristics simply appear common because respondents project culturally available vocabulary.

“You might eat an ice cream sundae and say ‘wow, that was marvelous,’ and someone else might have had a drink and call it marvelous. These words are not sufficient to prove anything about the fundamental comparability of those experiences,” he said.

But if we all feel marvelous, does it matter how we got there?

In his 1902 book Varieties of Religious Experience, philosopher William James was the first to argue that the merits of mystical or religious experiences derive not from their “roots” (origins) but their “fruits” (enduring effects). And, according to this study, the fruits look pretty similar. Both groups rated the experience as among the most personally meaningful and spiritually significant of their lifetime, reporting persisting positive changes in life-satisfaction, purpose and meaning as a result.

Amazingly, two-thirds of survey respondents who identified as atheist before the encounter no longer did, making me feel a little less crazy. Similarly, 70 percent of both the drug- and non-drug groups reported what I keenly felt: that what was encountered was “more real than real.” Perhaps this is why a majority of both groups endorsed that that which was confronted continued to exist even after the encounter ended.

Griffiths is arguably the foremost researcher on psychedelic-occasioned mystical experiences. He was motivated to examine “naturally occurring” “God-like encounters” — think Paul on the road to Damascus — because they have formed a fundamental part of the world’s religions for millennia. After conducting psychedelic trials in which participants reported deeply mystical encounters, his team was eager to understand how the two compared.

If we all feel marvelous, does it matter how we got there?

This study pokes the bear of a longstanding debate about whether psychedelic experiences are “genuine,” as compared to those induced by practices like prayer or meditation.

“‘Genuine’ is a word people have used to cast skepticism on psychedelic effects,” Griffiths said. “In this study, if we can’t measure any difference between them, one has to question whether they’re different. If it looks like a duck and walks like a duck, then it’s a duck.”

Not surprisingly, this claim irks at least some people in the religious community, including Katz, who rejected the fundamental premise of this exercise.

“Mystical experiences are engagements with an external reality. When you take a pill, your brain does funny things and you have a funny brain experience,” he said. “You haven’t had a mystical experience; you’ve had a psychological experience. Psychology is not the same thing as metaphysics. It’s not the same as Teresa of Avila saying she met Jesus.”

But the study doesn’t assert metaphysical claims about the reality of what survey respondents encountered — either with or without drugs. Griffiths is quick to point out that science can never definitively answer the question about the existence of “God,” a “Higher Power,” or “Ultimate Reality.”

“‘God can be found in a pill’ is definitely not an appropriate conclusion from this study,” he said.

But, at least in my experience, “an encounter-that-might-be-interpreted-as-‘God’ can be found in a pill” is.

What does it mean that experiences that have formed a fundamental part of the world’s religions for millennia could, in the future, form a fundamental part of our treatment of depression? If these experiences really are functionally indistinguishable, we need a whole new paradigm of mental health, one situated at the corner of spirituality and science, theology and therapy.

For example, Francis Guerriero, a spiritually integrated psychotherapist in Cambridge, works with clients who have encountered God both sober and through drug experiences, and treats them with similar tools. “The initial catalyst of encounters with divinity have no impact on the methodology with which I work to integrate them into a client’s everyday life,” he said. “Whether born of a drug experience or not, the key factor is ongoing and regular integration work."

But my regular psychiatrist had no interest in how my worldview shifted after the psilocybin trials, and didn’t understand how that shift might be capitalized to sustain mental wellness. But, thanks to efforts of groups like California Institute for Integral Studies and Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, an increasing number do.

When I asked Griffiths about the practical implications of his latest study, he emphasized the therapeutic potential of these experiences for increased well-being and greater mental health. Reducing “God-encounters” to their therapeutic potential feels like a breathtakingly transactional approach to the divine. But it’s one in keeping with our times. On the flipside, it suggests that we might begin to take seriously the spiritual dimensions of depression and other mental health problems. And while psychedelics could be an incredibly powerful tool to treat some conditions, they are not tools to be taken lightly. Because even if people like Katz say that drug experiences are psychological and not metaphysical, this study and my experience suggest they can mimic something that subjectively feels very metaphysical.

Reducing “God-encounters” to their therapeutic potential feels like a breathtakingly transactional approach to the divine.

And perhaps nothing short of a metaphysical shift — and a serious chemical ass-kicking — could disrupt my depression. Because at my worst, I felt exiled by an imagined cosmic arbiter that decides who is worthless (me) and who deserves to live on Earth (everyone else). Psilocybin thrust me back into conversation with a sense of Ultimate Reality, which — much to my surprise — welcomed me into my rightful place in the order of things.

Perhaps that is why, in a few blessed months after the trial, I glided through life on a cloud of equanimity and intensely present joy. When I awoke each day, the soft light of morning felt like a sweet drink I had never tasted, but one that I suddenly knew I deserved. I told everyone I loved that I loved them, two times over. Walking to work I was content to exist in the radiant suchness of all things, felt myself a purposeful part of existence, a rightful creature among creatures. My coworkers asked me if I had joined a cult. “You’re so zen,” they marveled. “What happened to you?” I wrote in my journal, twice on one page without realizing it: “I no longer feel like a prisoner of my own existence.”

One day, as my boyfriend drove me through unremarkable downtown Silver Spring, Maryland on an unremarkable day, everything felt remarkable. Surprising myself, I placed my hand on his and declared “I am just so happy to be alive.” And I watched his face turn from utter bewilderment to deep gratitude.

In a few blessed months after the trial, I glided through life on a cloud of equanimity and intensely present joy.

Severe, refractory depression is complex and requires continued maintenance. Even after my depressive symptoms reemerged — and they did — the meaningfulness of my encounters endured. It’s not that my despair had diminished; the frame around it expanded. And in that vast blessed blank space, I find divine okayness. The sense of being held by a great, ineffable Beyond makes it easier to hold my own suffering, and others’.

To study co-author Bob Jesse, founder of the Council on Spiritual Practices, the most promising finding relates not to the therapeutic potential of God encounters, but their surprising effect on religious tolerance: a high proportion of both groups reported increased understanding in religious or spiritual traditions other than their own.

I’ll admit: I was surprised to find that after my experience I no longer looked at places of worship with disdain. I guess I’ve become sympathetic towards the universal human impulse to self-transcend. Once a “secular” and inconsistent meditator, I now sit daily. I joined a weekly sangha and dedicated myself to reading Buddhist texts, seeking some tradition to scaffold my changed world.

When, during a follow-up session in the clinical trial, a researcher asked if i still identified as an atheist, the question didn’t surprise me as much as my inability to answer. Suddenly, the label felt like a shirt that had shrunk in the dryer: something that served me for a time, but no longer fit. What do you call someone who believes that things are likely better than they appear, and thinks that in light of this fact we should just be kinder to one another? Someone who suspects things are more mysterious than they seem, and more connected than we’ll ever know? Someone with an abiding conviction, grown out of a direct encounter, that there are things of ultimate importance that transcend ordinary waking consciousness?

I’ve become sympathetic towards the universal human impulse to self-transcend.

I almost dare not label these things, lest I become an idolater. All I know is that the felt sense of them keeps me company, even when I am alone.

No doubt, the debate about the authenticity of psychedelic encounters will rage on, fundamentally irresolvable. I keep returning to the Wallace Stevens quote, “God and Imagination are one.” I don’t care if my encounters were “authentic” or merely products of an imagination turbo-charged by chemical compounds. They felt real — more real than real — and are doing interesting and useful things in my life, and hopefully the lives of those with whom I interact.

I bet my childhood priest would be thrilled to hear I no longer doubt the possibility of a Higher Power. But I’d hate to see the penance he would hand down for doing psychedelic drugs.

Psychedelic drugs are currently illegal in most of the world and could be detrimental to your mental health if not approached in the right mindset and setting, or without proper integration after the experience. If you have had a difficult psychedelic experience and seek support, please visit https://www.zendoproject.org/resources/.