On a Saturday in November of 1966, the artist Tom Phillips walked into a discount furniture warehouse in search of a lifelong artistic collaborator. Among the store’s clearance book racks, he searched for threepence price labels, eventually stumbling upon a particularly old and yellowed volume that would serve as the source material for a sweeping and unparalleled project. That it cost only a few pennies was an added bonus.

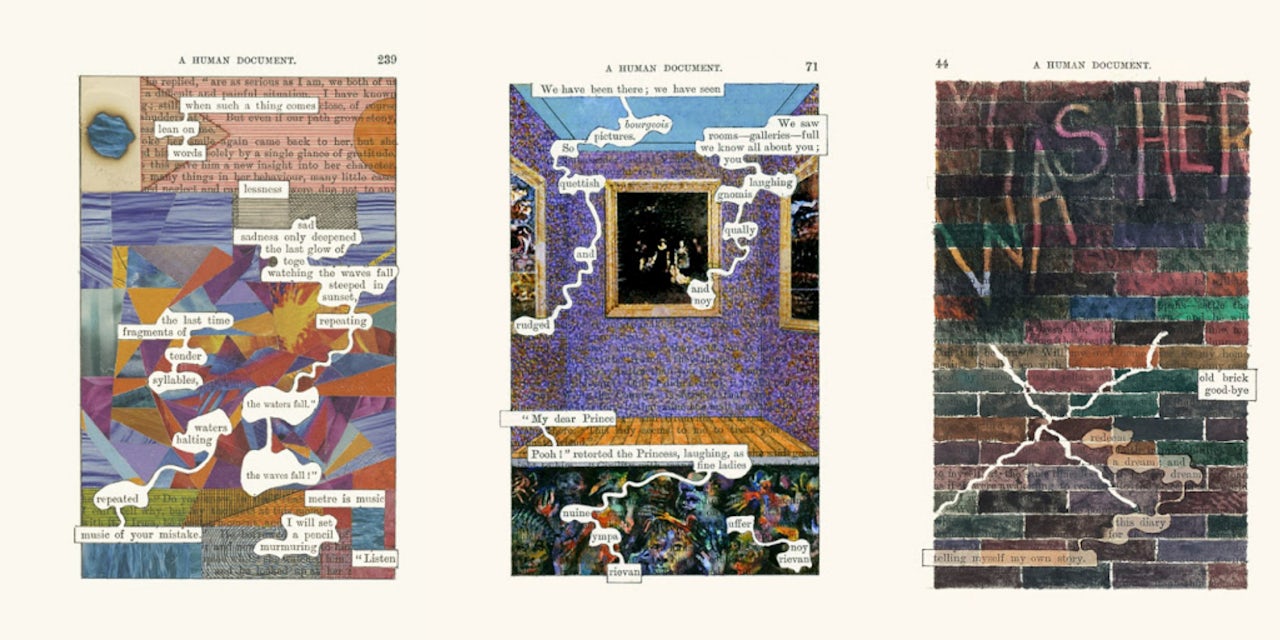

More or less at random, Phillips chose a Victorian novel called A Human Document. Over the next few years, he drew, painted, and collaged over every page, leaving just a few words uncovered per page. The result, A Humument, which was first published in 1980, is a collection of 367 pieces of bewildering, haunting, trippy, and beautiful artwork.

Phillips was born in 1937 in London, where he still lives. The breadth of mediums in which he works is difficult to overstate: His body of work includes drawings, paintings, wire sculptures, collages, murals, textiles, and music. He is a well-known portrait artist, having exhibited 160 of his portraits at London’s Natural Portrait Gallery in 1989, and his marble panels can be found in the iconic Westminster Cathedral. Alongside his friend and collaborator Brian Eno, he began to compose avant-garde works for orchestra or chamber ensemble with John Cage-esque graphic scores in the 1960s. But his greatest claim to fame is A Humument, for which he says the idea began to percolate after he began experimenting with his techniques on various scraps of text.

“I hadn’t really thought about it at all,” Phillips told me. “I just worked with other little bits, edges of pages here and there, thinking, how strange that these words occur in this way. And it was only that day when I bought the book that I thought, “I could do something on a larger scale with a proper book!” And [A Human Document] was the book. It all happened in a day!”

Phillips describes A Humument as a “treated novel,” the first of a self-invented genre, though he’s not the first artist or writer to create a new work of art from a previously existing text. The practice of making sculptures or other artworks out of books dates back thousands of years, while found poetry, created by selective deletion of a pre-existing work, has found modern popularity in books such as Jen Bervin’s Nets and Austin Kleon’s Newspaper Blackout. A Humument lives vaguely among these categories and more without narrowly belonging to any of them. “Neither a novel, a poem, an artist’s book, or a graphic novel,” art critic Sebastian Smee wrote in 2013, “[A Humument] is a little bit of all of theses things and one thing incontrovertibly: a masterpiece.”

When I first leafed through the pages of my college English professor’s treasured copy of the sixth edition of A Humument, I was struck with the sense that I held an important artifact of a specific moment — but it wasn’t apparent which moment that might be. The feeling split the difference between the awe you experience when viewing something beautiful preserved in a history museum, and the way a particularly weird piece of contemporary art might baffle and captivate you. In some ways, the book feels as old as its 1892 source material, but it’s also a work from 1973, when it was first displayed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, and from 1980, when it was first released as a book, and from 2016, when it was released in its final of six revised editions.

Over the course of decades, Phillips’ process of beautifying Mallock’s work morphed into a process of reimagining his own. Since the first edition of A Humument was published in 1980, Phillips has painted, drawn, or collaged over his original work on nearly every page, in some instances tracing new paths through different salvaged words. The second through sixth editions document his gradual revamping process, through textual and artistic changes ranging from subtle to complete overhauls.

“Often, I look at the pages in the final versions, and I think “that could be better,” he said. “So I look in the book again, and find something that I think is better. A lot of these pages are old friends or old enemies depending on whether I got stuck with them or something. It’s all like plowing the same field again for another crop.”

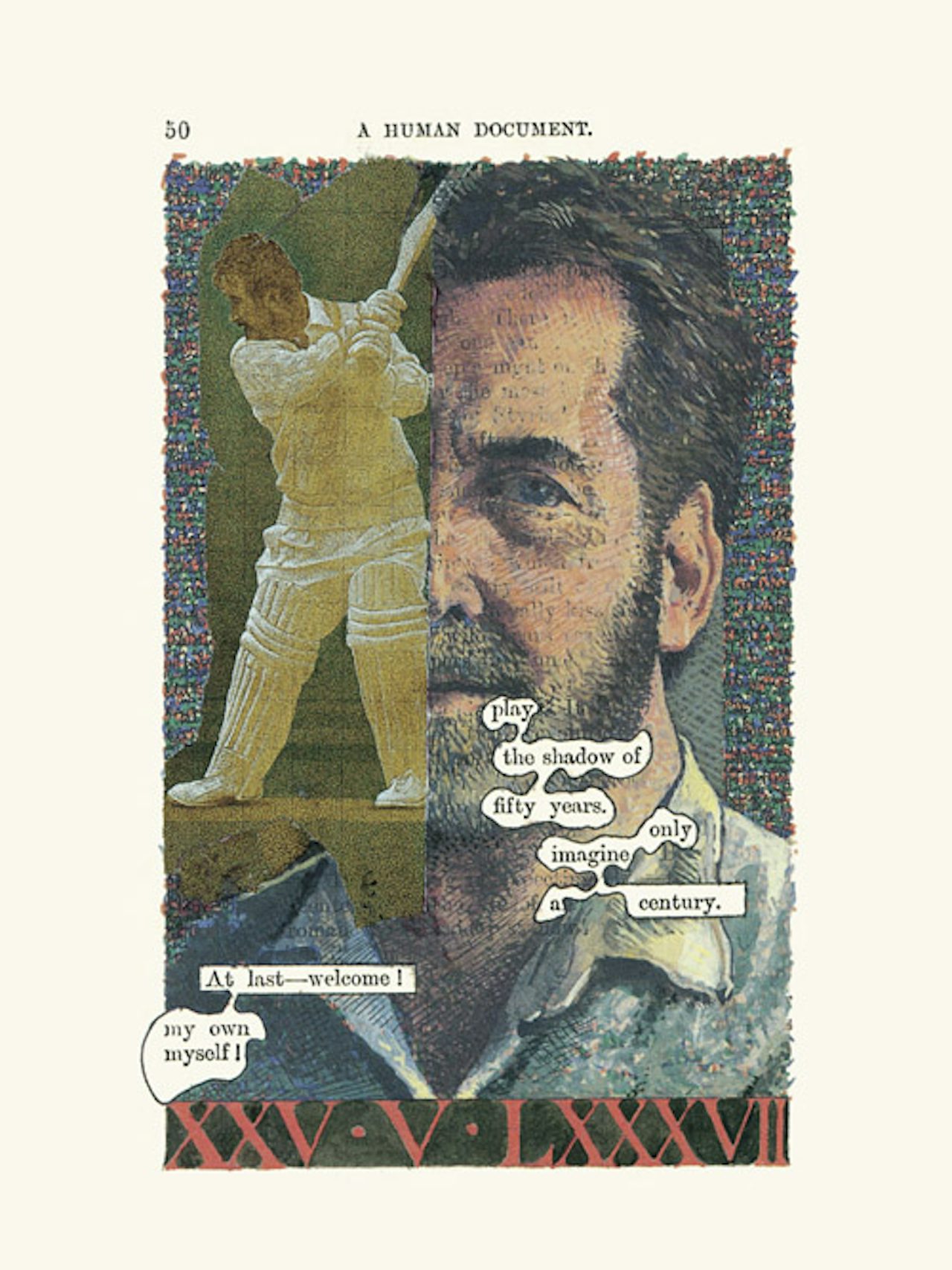

The narrative of A Humument, insofar as one exists, remains constant across editions. The text reads as a diary describing the love story between a woman named Irma and a man named Bill Toge, whose last name surfaces every time Mallock’s text uses the word “together.” Phillips himself makes appearances within the book; on one page, the words “At last, welcome! / My own myself!” accompany his self-portrait.

On the meta-textual level, however, A Humument seems to be primarily concerned with history — of its source text, of the world in which that text went mostly overlooked for many decades, and even of its own transformative process. Phillips’ source material, A Human Document, is one of the many novels written by the English writer W.H. Mallock. When he is remembered at all, Mallock is remembered primarily for his Victorian-era political satire and anti-socialist polemics such as The New Republic — his less political novels like A Human Document are by and large obscure.

Phillips says that he has never sat down and read A Human Document cover-to-cover in his many decades working with the text, but has spent so much time combing through its pages that he has become familiar with the story and its characters, and above all else, its use of language. “His book is a feast,” he writes in the introduction to A Humument. “I have never come across its equal in later and more conscious searchings. Its vocabulary is rich and lush and its range of reference and allusion large. I have so far extracted from it over one thousand texts, and have yet to find a situation, statement or thought which its words cannot be adapted to cover.” (The text is, in fact, quite lush; in an early, page, the narrator describes a character’s idiosyncratic writing “as if her language had been broken by it, like a forest broken by a storm, or as if it were some living tissue, wounded and quivering with sensation.”

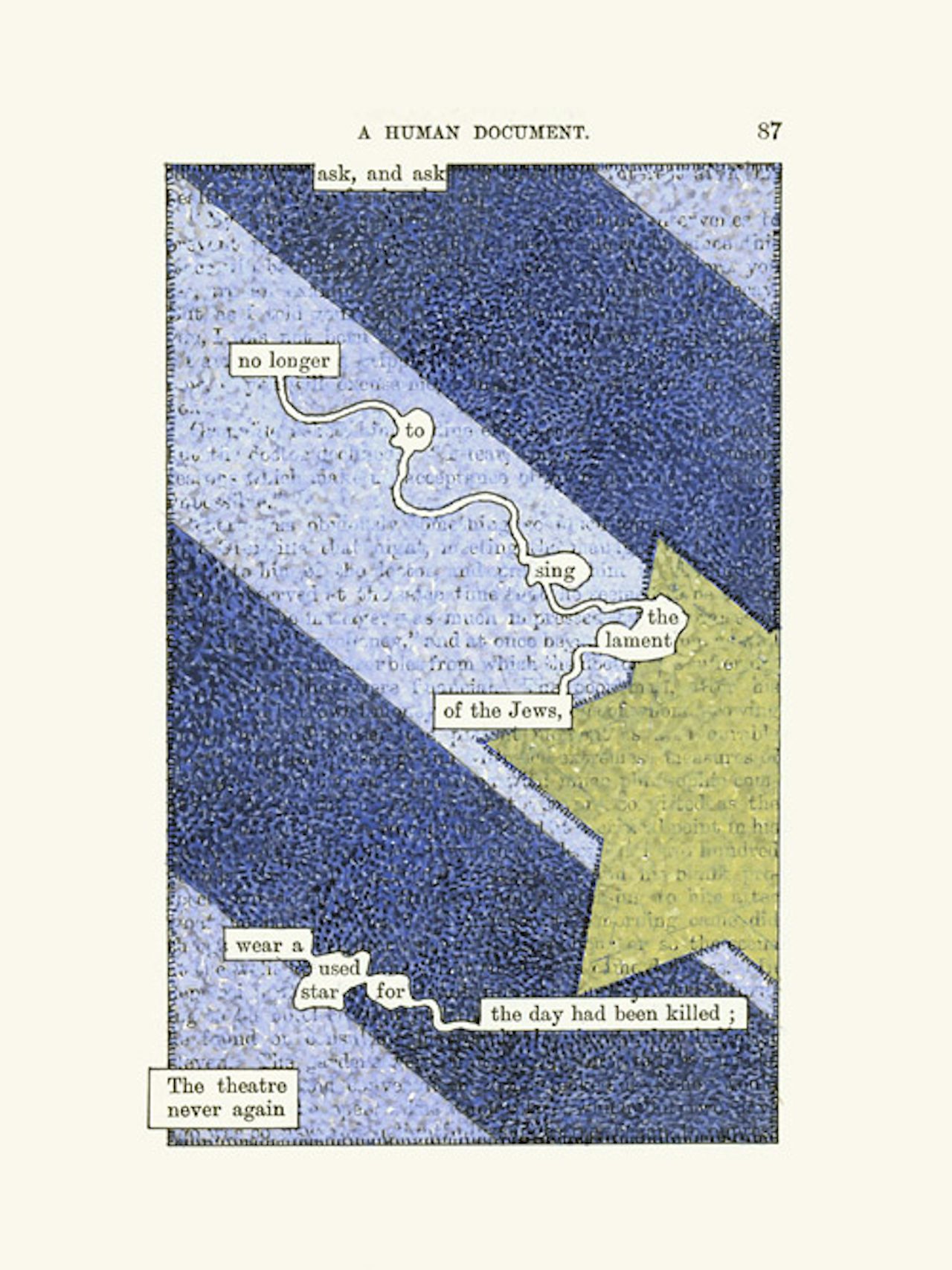

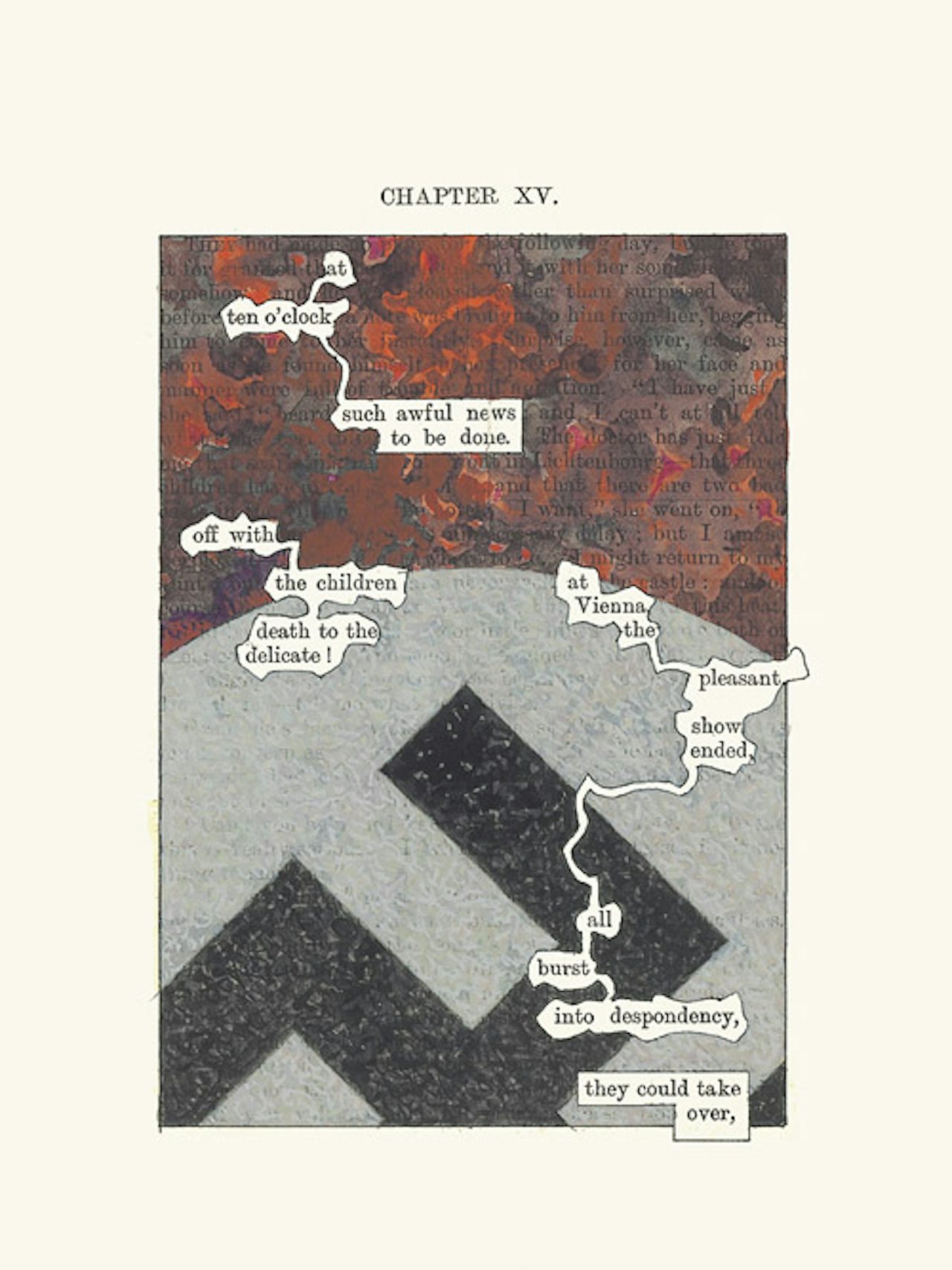

Mallock was also, among other things, a racist and anti-Semite. Overt anti-Semitism is central to the plot of A Human Document; the story revolves around a man and woman engaged in a love affair, made morally excusable by the fact that the woman’s husband is Jewish. For Phillips, Mallock’s bigotry is key to the mission of A Humument. In reshaping the text and covering the rest with art, he is able to turn an artifact of hatred into something beautiful.

This dynamic is most explicit when Phillips turns his attention to the history between A Human Document and A Humument. The book makes reference to the Holocaust, which began nearly half a century after the release of A Human Document, on multiple occasions. In the original text, a man is manipulated by Jewish people from whom he’d borrowed money. Out of this anecdote, Phillips crafts a haunting fragment, with tiny dots of paint and ink forming a gold Star of David and grey stripes across the page. Elsewhere, he covers the page in part of a swastika against a bloody-looking red-and-black watercolor background.

These pages are viscerally horrifying precisely because they rely on the present-day readers’ knowledge of events unanticipated to readers of *A Human Document in 1892. Reading them for the first time made me feel like I was watching a car barrel around a blind corner towards an unsuspecting pedestrian at full speed. History, the pages seem to shout at you, is something that we actively create and recreate with every retelling.

The layered relationship between old and new text is used for levity, in addition to somber reflection. “remember / bush / bush / remember that bitter name / remember him. The rude stare at destiny,” reads one page decorated with ’60s comic book-style collage. An early page references Facebook. The anachronistic tension is not only with Mallock’s work, but also with his own, as he paints over pages he first decorated well before Facebook existed or George W. Bush was president. “The last two [versions] couldn’t have existed before the events that they reflect, because the language is changing all the time,” he said, mulling over one of his newest pages, a tribute to the #MeToo movement in which four red-and-green hashtags frame a watercolor portrait of a woman. “#MeToo didn’t mean anything until very recently, and so, that leaps out of the page. It was always there, but it didn’t mean anything [until the #MeToo movement].

I think of A Humument as a sort of Theseus’s Ship of the art world. Is the first edition even the same book as the sixth, with nearly every page having been changed? Phillips has a distinct visual language that remains constant across editions, but his style is so eclectic and varied that the meaning of each page inevitably changes between first and later editions. On my first reading, I wondered if the extent of the changes over time meant that the later editions are more akin to sequels than updates. I eventually came to view them as neither sequels nor updates, but various windows into the evolution of a project with no discernable end point.

As the years and then decades passed, Phillips’ relationship with the text of A Human Document began to pervade his art outside the scope of A Humument. Soon after beginning work on A Humument, Phillips began composing Irma, an opera based on the book and named for one of A Human Document’s central lovers. He has also produced stand-alone collages, paintings, and a decorated skull featuring fragments of Mallock’s text. His appetite for source text to create art from seems to only be satisfied by A Human Document. “That Mallock and I were destined to collaborate across a century became quite clear,” Phillips writes in his introduction, “when I tested other fictions and discovered nothing equal to him in the provocation of fresh conflations and marriages of word and phrase.”

The sixth edition of A Humument, released in 2016, was marketed as its final full edition. Phillips, now 82, has continued working on new pages, however, occasionally posting new treatments of pages on Twitter and Instagram.

Art historians of the future will likely find Phillips’s oeuvre as difficult to categorize as A Humument itself. Perhaps he’ll be remembered as a “picturesmith, wordsmith, and occasional musicsmith,” as his Twitter bio describes him, or as the founding father of the “treated novel” genre. I’d like to think that A Humument will be remembered as I have come to think of it, not even as a book so much as a one-man art movement, a beautiful, witty, haunting reckoning with the past in its innumerable telling and retellings, constantly expanding even as it trolls the same, seemingly unchanging clearance-rack novel.