On August 16, in a dusty corner of the Internet, a 15-year-old blog coughed out one final post and went defunct. That post, the resignation of the founder and self-described “blogmistress” Melissa McEwan of the website Shakesville, came after a month-long hiatus and years-long decline.

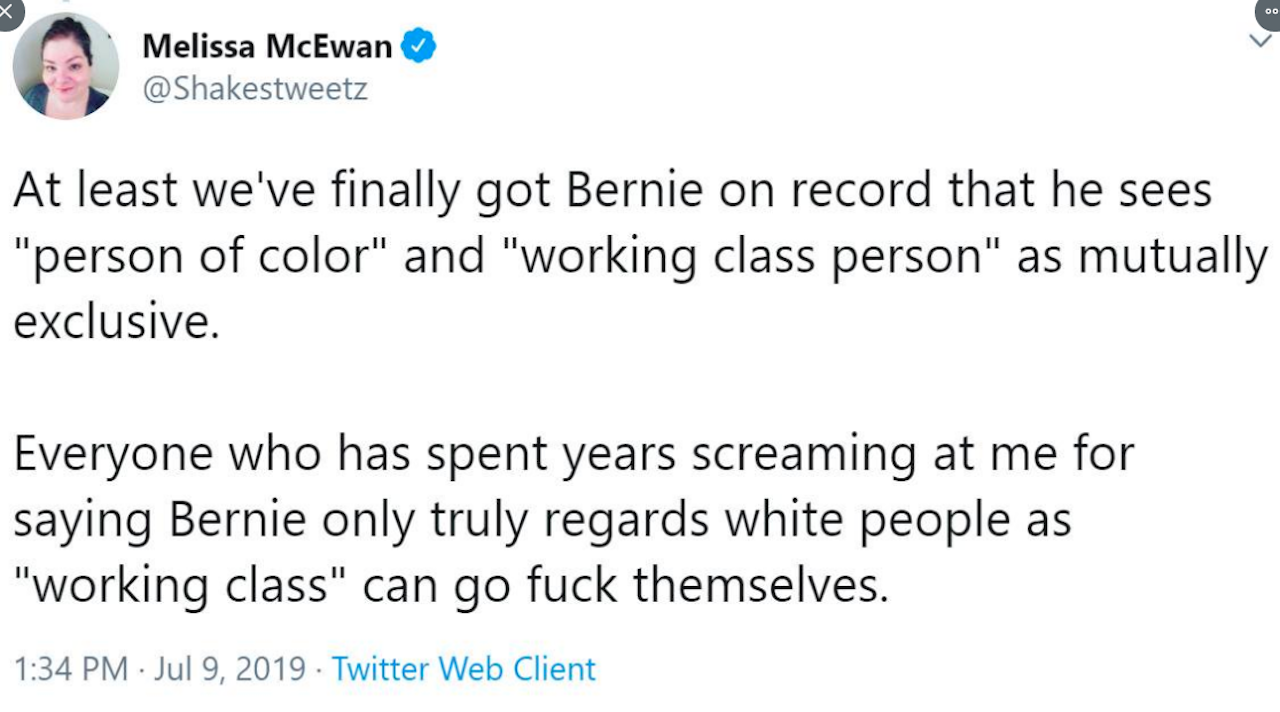

If you recognize McEwan’s name, it’s probably because of her impressive ability to get roasted on Twitter, often by people who have been making fun of her since the Internet was only on computers. Maybe she counted every word in the Captain Marvel trailer, concluded that Samuel L. Jackson had more lines than Brie Larson, and charged it with sexism. Or she saw Bernie Sanders’ phrase “person of color or working-class person” as evidence that he believes those groups are mutually exclusive. No matter the day’s offense, the discussion inevitably turned to Shakesville: a PC nightmare, a cult, a joke.

Shakesville started in 2004 as Shakespeare’s Sister, a group blog with a goofy streak. It soon became a moderately popular politics-and-feminism destination, a respected member of the progressive cohort that included Daily Kos, Eschaton, and Feministing. McEwan, an Indiana native and Loyola University Chicago graduate, worked in marketing before transitioning to full-time blogging. In 2005, she invited me — handle Tart, then journaling at my own tiny Blogger subdomain and commenting at Shakesville — to join as a contributor.

At that time, a group blog meant that several writers contributed posts to it centered on a shared philosophy or genre. Shakesville published anywhere from three to 13 posts per day and had dozens of regular commenters. Anyone could create a Blogger (later Disqus) account and comment; threads were moderated, but only obvious trolls were deleted or banned. The size of the writing “staff” (we were not paid) varied over the years, but in 2009, when a single post could net upwards of 200 comments, the blog had 15 regular contributors including McEwan.

In its early days, a typical Shakesville comment thread was a freewheeling affair full of jokes and wordplay and cringey (but, I assure you, very cool at the time) snark. We expressed frustration at homophobes by typing “OH NO TEH GAY!!!1eleven!!!” and came up with dozens of ways to call George W. Bush an illiterate child. I hosted a feature called Tart’s Poetry Corner, where we chatted about James Dickey and Sharon Olds. We made real friends. The stakes were low.

But somewhere around the 2008 election, under the pressure of moderate popularity, Shakesville suffered the Internet equivalent of a collective psychotic break.

I suppose you could blame Barack Obama. Liberal bloggers of the aughts were first and foremost anti-war; we hated the Iraq invasion, we were discouraged by Bush’s re-election, we were queasy at the flag lapel pins and all that Lee Greenwood shit. Then two things happened: the financial markets crashed and a charismatic senator from Illinois dazzled us with new promises. Jacob Bacharach, who blogged at Who Is Ioz? during that time (and is also a current Outline contributing writer), recently told me he believes Obama “successfully co-opted the liberal heart of the anti-war/anti-Bush coalition and incorporated it into his movement.”

At some point in Obama’s first term, it became clear that the war in Afghanistan would not end; Guantanamo would not close; the Bush Administration would not pay for torturing prisoners. Air strikes in Libya and Yemen and drone program expansion confirmed that Obama would wage war with fewer combat troops, but he would wage it nonetheless. Distracted by domestic concerns, a large part of the online left gave up. Progressive blogging slumped as readers moved on to Facebook and Twitter. At Shakesville, the sea change was punctuated by some serious internecine drama.

In a November 5, 2008 post titled “Great Expectations,” McEwan and urged optimism from the community. What resulted became known to former Shakers as the Great Meltdown.

In early 2007 McEwan was hired, along with Amanda Marcotte, who was running the liberal blog Pandagon, to blog for the John Edwards presidential campaign. Both were soon forced to quit after Catholic activist Bill Donahue called them bigots and lobbied for their removal . The incident made national news and McEwan achieved what I assume was dizzying notoriety, not least because it attracted a wider variety of troll to her blog and inbox. According to former Shakesville contributor Litbrit, when McEwan tried to move the blog to a new domain, it was subjected to DDOS attacks. She was doxxed and reported that she received rape threats. It is perhaps unsurprising that an air of paranoia became increasingly palpable at Shakesville. (McEwan did not respond to an email requesting comment for this piece.)

In a November 5, 2008 post titled “Great Expectations,” McEwan praised Obama’s victory and urged optimism from the community. What resulted became known to former Shakers as the Great Meltdown.

It’s easy to assume that McEwan, Dr. Frankenstein-like, built a monster she could no longer control, but when I read through that thread now, I don’t see an over-abundance of negativity. I see, with the exception of a couple smartasses, people skeptical of the country’s ability to reform itself after eight years of jingoism and war, and a few PUMAs who thought the nomination was stolen from Hillary. The mods wouldn’t abide this, and all hell broke loose. In the comments, McEwan appeared exasperated, claiming to be “hanging on by a thread.” She threatened to quit blogging forever. Readers departed en masse. According to Google Trends, searches for “Shakesville,” which reached an all-time peak that September, had by December dipped by 50 percent. This is about the time I myself stopped reading the site entirely.

In June 2009, after a few comment thread blow-ups and several days without posts, the blog’s 14 contributors posted “‘All In’ Means ALL of Us,” a manifesto intended “to address what we see as an ongoing and extremely problematic pattern within our community.” The pattern was the rampant disrespect of McEwan. They called on Shakers to “bring your vocal, visible support to Melissa (and other contributors) when you see others disrespecting them” and pledge to respect her as “acknowledged leader.”

The result was, in Shakes-speak, a clusterfucktastrophe. The first comment, and most upvoted, got right to it: “Is this a blog or a freakin’ cult?” Many Shakers pledged to be All In and promised to participate more, but a significant number reported being turned off and insulted. Readers fled to other blogs and Facebook to vent and regroup. According to a screenshot sent to me by a former contributor who asked to remain anonymous, McEwan emailed contributors asking to be kept apprised of negative comments about her. But many offending Shakers never returned.

From the beginning, Shakesville appealed to survivors of sexual assault and dysfunctional relationships. As former mod Persephone (name has been changed) told me, “Melissa attracted a lot of vulnerable people to the blog.” They clung to her, grateful to be taken seriously; one commenter referred to “key times in the past that Shakesville helped stop me from walking into the desert, to live or die, it didn’t matter.” Another wrote that McEwan was “the voice for so many who are afraid.”

Having that strength used against them created a familiar sense of betrayal; the Great Meltdown reminded these loyal readers of their narcissistic parents and abusive partners. Starting in 2013 former Shakers began using a Tumblr page called Drink the Shaker Kool Aid to share stories about what they call the blog’s abusive environment. One former reader remembered “the same punishment/repentance/groveling/barely accepted apology cycle” of a conservative religious childhood.

Shakesville had promised to be a safe space, a “refuge from the entire rest of the world where people who deviate in some way from arbitrary norms are ridiculed.” The term “safe space” has become a joke, but it’s worth examining where it came from. So much of the Internet was mean, reptilian, scary for women. Shakesville would be expansive and accommodating. To this end, trigger warnings — which McEwan later called content warnings — began appearing at the top of almost every post around 2007. They were unexpectedly specific: Trigger warning for discussion of “enhanced TSA screening.”Trigger warning for large reptiles.Trigger warning for Christian supremacy. Content Note: Discussion of trigger warnings.

To anyone steeped in Insta-inspo or Twitter irony, these liturgies are either perplexingly fusty or unnervingly self-serious. To a Shaker, they were church.

Then there were the language rules. Ableism was out (idiot, moron, crazy, insane, lunatic), as were fat-shaming and food-policing; at Shakesville, you never forgot that your physical body and your politics were inextricable. You would encounter the word kyriarchy and the pronouns zie and hir, perhaps for the first time. There were slogans: Shakers “work their teaspoons,” ready to empty an ocean of injustice, and they “expect More.” When two commenters expressed reservations about this, citing discomfort with group credos, McEwan replied that “sloganeering… has a deeply feminist history.”

Because Shakesville was largely a closed system — McEwan’s feminism posts link almost exclusively to her own work; readers were rarely directed to other feminist thinkers — you can find a Shakes-reason for anything. There’s a lot of repetition; McEwan frequently recycled content from old posts into new ones. The “How Are You?” posts, where she checked in on the commentariat, reliably contained the incantation “I continue to loathe the entire Trump Regime with the fiery power of 10,000 suns.” Since 2009, McEwan had been copy-pasting the following, including in a 2017 post in which she compares herself to Martin Luther King, Jr.: “I dream long and lustfully of a better world that is both my muse and objective. I want it like the cracked earth of the desert wants rain, and I will neither apologize for nor amend my desire because of its remove from the here and now; its distance encourages my reach.” To anyone steeped in Insta-inspo or Twitter irony, these liturgies are either perplexingly fusty or unnervingly self-serious. To a Shaker, they were church.

Below each post a notice stated that one must read the Commenting Policy and all of a post titled Feminism 101 before commenting. By my count, the Commenting Policy is 15,000 words long, including linked Shakesville posts. Feminism 101 is a roughly 22,000-word annotated bibliography of 182 posts dating from 2006 to 2012. In total, new commenters were asked to read approximately 205,000 words, about the equivalent of Moby-Dick, before typing a single sentence at Shakesville.

Nobody was going to read all that, and it didn’t matter. The disclaimer bestowed power. One commenter, quibbling with McEwan over the British definition of “brilliant,”, was admonished that, as the wife of a Scotsman, McEwan understood UK usage, and doing the “required reading” would have kept the commenter from being “ignorant of this fact.”

But for many Shakers the commenting policy also created, in the words Persephone, “a place where the basics weren’t up for debate all the time.” You didn’t have to indulge recreational devil’s advocates or explain why abortion should be legal to someone claiming to be genuinely curious. McEwan called this an advanced feminist space.

Were all of these rules about ego or ethos? Was it about destroying criticism and controlling the conversation, or creating a respectful community? As the Commenting Policy stated, “usually, what looks the most like our being ‘mean’ is our fiercely protecting this community.” In other words, hostility is the rough side of kindness, and users who behaved will be protected. This is what progressivism shouldn’t be: more focused on in-group civility than a wider justice. Acceptance is meaningless without grace.

The community, meanwhile, was very happy to police itself, especially the most notorious mods: Paul the Spud, a vocal McEwan admirer and her IRL friend; PortlyDyke, a self-described “psychic and full-body channeler”; and the infamous Deeky, another IRL McEwan pal known at ShakerKoolAid as her “attack poodle.” According to Persephone, “Deeky was a bully…the first to attack someone for being disloyal to the blog or to Melissa.” Readers learned quickly. One ShakerKoolAid poster said a scolding from Deeky taught them to “play the game well enough to occasionally comment without much fear.” Persephone told me that Deeky “kept people in that heightened ‘find the one who doesn’t belong’ mindset” and that she realizes now, with some embarrassment, “how easy it is to be swept up, almost addicted to the high of that cult behavior, going after people who weren’t in line.”

And much like other dedicated groups, sometimes tithes were requested. There were no ads on the site, but a donations-only model sometimes required aggressiveness. In 2009 McEwan, having begun periodically reminding readers that Shakesville was her full-time and only job, wrote that she must fundraise or “be shit broke.” Claiming to be running the site “for less than minimum wage,” she asked readers to prove that they valued her “woman’s service work.” Former Shakers argued that McEwan’s claims to penury were false because her husband was employed. But McEwan reasoned that she should be able to support herself on her own income; in her words, “every donation is a feminist act.” In what would later become an example of Shakesvillian greed, Paul told a Shaker pledging the last $5 on their child-support card that “no amount is too small.”

Shakesville’s archives reveal a tiny Internet kingdom with a complicated queen, though McEwan described herself as “a mentor, a de facto social worker,” a “Cassandra” who saw Trumpism coming and wouldn’t apologize for frequently being right.

In February 2018 she complained about being mocked on Twitter for her work at Shakesville, spending “an enormous amount of my time every weekday creating a detailed compendium of many of this administration’s abuses,” and receiving in exchange “exasperation and scorn.” In March of this year she predicted that the left will desert anti-Trump activists like herself, leaving her in danger. In May she appeared to refer to ongoing troubles with the Bernie Sanders crowd, citing “the personal abuse I am obliged to navigate simply by virtue of covering candidates with very aggressive supporters.���

Shakesville was an object lesson in easy targets, and McEwan was fun to hate.

It’s a common problem for online polemicists: after enough screeds, uncharitable readers know what to expect and will often dismiss the entire arguments outright without addressing the individual points. But this works to the polemicist’s advantage: you can allege that detractors refuse to engage with your ideas because they’re too challenging. If you’re being attacked from all sides, you must be on to something. This strategy works for Quillette contributors and alt-right-friendly podcasters, and somehow they still get away with accusing liberals of crying victimization.

Shakesville was an object lesson in easy targets, and McEwan was fun to hate. To conservatives, she was a totem of the PC culture they revile. To leftists, she was a neoliberal phony. Her brand of commentary was desperately uncool, sarcastic but somehow irony-free. When she described being overworked and unappreciated, one Shaker mused that she deserved a “magic elf” assistant. McEwan called this “dehumanizing.” She wrote, “magical content-generating elves don’t exist, so your saying I should get one is, in reality, for me, an admonishment that I should do EVEN MORE.” Leak this evangelical-vlogger-level righteousness onto Twitter and get mocked from all quadrants of the political compass.

McEwan was also brave, and bravery is infectious; people will admire it, emulate it, mock it, destroy it. Shakesville’s entertainment value came from the tension between McEwan’s displays of stubborn courage and her strident self-seriousness. Unlike many bloggers, McEwan stopped using a pseudonym very early on. She posted “fat fashion” photos of herself despite how the Internet treats fat people, especially fat women. She wrote about being raped. In 2017, one of the Chapo Trap House guys made a tasteless joke about a #MeToo tweet she wrote; he later apologized on Reddit and promised to donate to the Center for Reproductive Rights. McEwan tweeted that the money should go to her. You almost have to admire it.

The left blogosphere grew out of real need. We read Steve Gilliard, Atrios, and Shakesville because their frustration, incisiveness, and humor felt like an antidote. Our own writing was a release. I have scooted leftward in the last few years, but I’m still the progressive feminist I became in blogging’s golden age. As Litbrit told me, “I wouldn’t change those years — they sharpened certain skills for me.” Moreover, a blog was a location where, as former bloggers told me, they could “hang out.” Many former Shakesville participants said they’re grateful to the blog for giving them guidance, clarity, and friendship.

The 2013 “sundowning” of Google Reader ushered us into the age of the algorithm; an invisible engine would now select your favorite content for you. Today, your online social interaction is most likely facilitated and mediated by a multi-billion-dollar corporation. If you go out searching for articles or YouTube videos on your own, you’ll see what Google wants you to see. So it’s easy to be nostalgic for a version of the Internet that’s never coming back. It’s easy to create false memories of a web of niche hangouts you sought out yourself or found linked on favorite blogs.

Shakesville is over, and the era of progressive blogging is, too. Sure, some of those sites are still around. Daily Kos updates every day, but an assessment of its relevance should hinge on the fact that founder Markos Moulitsas hosts fundraisers so he can hand-deliver bouquets of roses to Nancy Pelosi as a thank-you for doing her job.

It always confuses me when people talk about social media echo chambers. Filter bubbles notwithstanding, I see all sorts of online content I could do without. I go to Facebook and see your cousin complaining about immigrants; Instagram thinks I’m in the market for a subscription box of hideous pastel “personalized artist designed enamel pins”; people will never stop retweeting fucking Ben Shapiro videos onto my timeline. Meanwhile, at the height of the platform’s powers, a blog could easily assemble a readership that spoke with one collective voice.

That’s not necessarily a negative thing; who doesn’t want to talk to people who share their values and interests? But you get used to agreeing on basic principles, and when some hapless new commenter wanders in, maybe the Cool Kids Club flames them and laughs about it. Sometimes you’re that hapless newcomer and it sucks. Just like Twitter. Platforms and styles of commentary may change, but those networks are still made of people, and we are the same as we ever were. It’s not particularly useful to think in terms of golden eras. The Internet was always awful, and I’m never leaving.