On September 22, 1982, the second year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the first episode of Family Ties aired on NBC. The sitcom’s opening scene depicted a family gathered in their living room, watching a slideshow of old photographs. But these weren’t snapshots of family vacations — they documented the parents, Steve and Eylse Keaton, in their youths, at a protest against the Vietnam War. Former student activists at Berkeley, the Keatons were now middle-aged, gainfully employed adults in Columbus, Ohio. At its outset, the story was supposed to be about them, and the struggle to remain faithful to ideals even as aging encourages compromise.

But it was the Keatons’ son Alex, played by Michael J. Fox, who stole the show. A young Republican, dressed somewhere between New England preppie and Wall Street business casual, Alex stood as a foil for his parents’ idealism. With a poster of the conservative economist Milton Friedman on his bedroom wall, he had a tendency to apply extreme free-market principles to matters as mundane as household chores. Alex’s incipient authoritarianism caused nothing but trouble, and by the end of just about every episode he would apologize for something he had done. But Fox’s natural charm made him seem like the protagonist of the show.

Alex P. Keaton was either prophetic, or influential, or both — not just because conservative public figures like Tucker Carlson and Ben Shapiro appear to have modeled themselves on him. In the recurring Western psychodrama of adolescent rebellion, it seems perversely natural that the leftward cultural shift of the ’60s and ’70s should be followed by a conservative reaction. Antonio Gramsci, a Marxist theorist and founding member of the Communist Party of Italy, described this historical cycle succinctly in his Prison Notebooks, written as he served a life sentence in one of Mussolini’s jails. “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born,” he wrote. “In this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

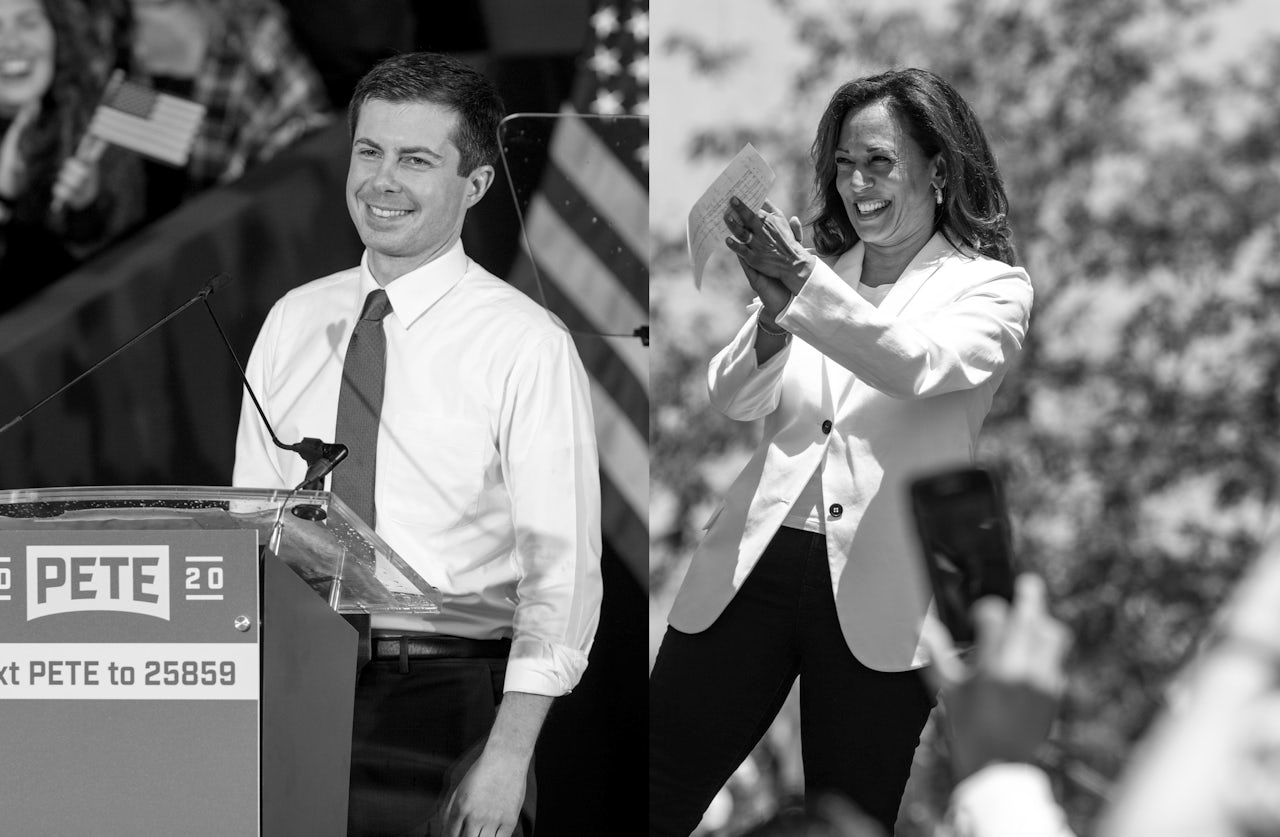

Morbid symptoms certainly abound in our time, with one of them sitting in the White House. But the underlying sense of stasis, the refusal to be born, has found its own acolytes in contemporary politics. It has been on full display in the Democratic Party. One such representative is Pete Buttigieg, Mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and a candidate for president. At 37, the clean-cut young Navy veteran and former McKinsey consultant is the youngest person running, yet possesses the least-youthful disposition in the race.

At the last Democratic debate, after a tendentious exchange between Julián Castro and Joe Biden, Buttegieg calmly rebuked his elders. “This is why presidential debates are becoming unwatchable,” he said. “It reminds everybody of what they cannot stand about Washington. Scoring points against each other, poking at each other, my plan, your plan. Look, we all have different visions for what is better—” His sermon was blessedly interrupted by Castro, with a somehow necessary reminder: “Yeah, that’s called the Democratic primary election, Pete.”

"This is why presidential debates are becoming unwatchable," Pete Buttigieg says after Julian Castro and Joe Biden argue over health care.

— ABC News Politics (@ABCPolitics) September 13, 2019

Castro: "That's called an election"

"A house divided cannot stand," Amy Klobuchar chimes in https://t.co/OeZnH02wCu#DemDebatepic.twitter.com/0y0DxcnqkQ

Ironically, the better part of Mayor Pete’s paternalistic attitude is generally reserved for two of his oldest opponents, Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. “My concern about the vision from the Sanders/Warren approach is that it can polarize Americans,” he recently said on CNN. He told the New Yorker that his generation’s most salient political element is “pragmatism,” and he endlessly alludes to “common sense.” But recent polling shows that Buttigieg’s support among among voters aged 18 to 34 is negligible — a mere four percent, compared to a combined 64 percent for the Sanders-Warren approach.

Why is Buttigieg, the first arguably Millennial presidential candidate, so leery of even slightly radical politics? In might be that his heritage lies in a revolutionary intellectual tradition. For all his appeals to the middle, mayor Pete has described his father as a “man of the left.” Joseph Buttigieg was a literary scholar whose work specialized in none other than the writings of Antonio Gramsci. In addition to writing multiple monographs on Gramsci’s thought, Buttigieg was the translator of the complete edition of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, published in three volumes by Columbia University Press, and a founding member and President of the International Gramsci Society.

Gramsci’s analysis of society was based on the fundamental polarity underlying Marxist thought, between a ruling class and the masses. This was enforced by the rulers of society and the owners of the means of production, who required the consent of citizens to exchange their labor for a wage. While earlier societies extracted labor through coercion, capitalism operated by persuasion. This was what Gramsci, in his most famous contribution to social theory, called “hegemony.” When hegemony becomes an effective force, it attains the level of “common sense” — the unquestioned obligation to work for a living. Gramsci’s critical stance is not one that Buttegieg the younger seems to have inherited. “American capitalism is one of the most productive forces ever known to man,” he told CNBC, in a strange echo of Marxist terminology that declines to acknowledge or oppose exploitation.

As the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips wrote in his book On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored, “adolescence too easily involves, as only adults can know, the putting away of the wrong childish things.” And Buttigieg, who leads the polls after Biden, Warren, and Sanders, is not the only Democratic candidate to invert adolescent rebellion. Directly beneath him in most polls is former California Attorney General Kamala Harris, who combines centrism with cheerful allusions to her past as a state prosecutor.

Uncannily like the Keatons, Harris’s parents met while student activists at Berkeley. Her father, Donald J. Harris, now a professor emeritus at Stanford, was the first and only black professor in the university’s economics department when he arrived there in 1972. According to an article in the Stanford Daily from 1974, Harris was one of two Marxist economists on the faculty at the time, a distinction that almost cost him his position. His unconventional research interests, not to mention his background, made him a target for suspicion; an op-ed in the Daily described him as “too charismatic, a pied piper leading students astray from neo-classical economics.”

While Harris’s work consisted of papers with titles like “Capitalist Exploitation and Black Labor” and "The Black Ghetto as 'Internal Colony,’” his daughter’s mode of thought has gone in a different direction. “I believe in capitalism,” she recently assured a party of wealthy donors in the Hamptons.

During Harris’s tenure as California’s attorney general, 1,974 people were jailed for marijuana possession, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Once an opponent of California legislation to legalize marijuana, Harris has since come to find her position as a commander-in-chief of the War on Drugs an inconvenient one for her political aspirations. When asked on the radio show The Breakfast Club whether she had ever smoked pot herself, Harris answered, “Half my family’s from Jamaica, are you kidding me?” Her opportunism was all too transparent, to the elder Harris’s chagrin. A statement he sent to Jamaica Global was surprisingly vitriolic:

My dear departed grandmothers (whose extraordinary legacy I described in a recent essay on this website), as well as my deceased parents, must be turning in their grave right now to see their family’s name, reputation and proud Jamaican identity being connected, in any way, jokingly or not with the fraudulent stereotype of a pot-smoking joy seeker and in the pursuit of identity politics. Speaking for myself and my immediate Jamaican family, we wish to categorically dissociate ourselves from this travesty.

The Harris campaign has declined to comment on her father’s statement. But in spite of attempted appeals to rising disenchantment with the American War on Drugs, Harris has not shied away from making reference to her work as a prosecutor, alluding to it frequently in her campaign messaging.

Buttigieg has also sided, embarrassingly, with the forces of coercion, mishandling a police shooting under his mayoral administration and openly opposing citizenship rights of felons. As he said in the first Democratic debate in April, “part of the punishment when you are convicted of a crime and you’re incarcerated is you lose certain rights, you lose your freedom, and I think during that period it does not make sense to have an exception for the right to vote.”

That loss of freedom would have been familiar to Gramsci. The translators of a previous edition of his Notebooks described his life in captivity:

At his trial in 1928, the official prosecutor ended his peroration with the famous demand to the judge: “We must stop this brain working for 20 years!” But, although Gramsci was to be dead long before those 20 years were up, released, his health broken, only in time to die under guard in a clinic rather than in prison, yet for as long as his physique held out his jailers did not succeed in stopping his brain from working. The product of those years of slow death in prison were the 2,848 pages of handwritten notes which he left to be smuggled out of the clinic and out of Italy after his death.

The Marxist family line of two of the Democratic Party’s most visible centrists is a strange coincidence, but this Oedipal tendency in Western politics was perhaps anticipated a decade ago in the UK. The British sociologist Ralph Miliband, whose 1961 book Parliamentary Socialism announced his intentions with a scathing critique of the Labour party, called for the radicalization of electoral politics with the energies of organized labor as a means of enacting socialism in English society. Increasingly disillusioned with the party’s direction, he died in 1994, the year Tony Blair became its leader. Miliband’s sons Ed and David would go on to help dismantle his father’s life’s work as members of Blair’s cabinet during the Labour party’s increasingly accelerated move to the center. Meanwhile, Tony Benn, an icon of the Labour Party’s left flank and an associate of Ralph Miliband’s, retired from Parliament in 2001 and dedicated himself to protesting the British government’s alliance with George W. Bush’s military adventurism. In 2003, Benn’s son Hilary, who had also become a member of Blair’s cabinet, voted in favor of the Bush Administration’s invasion of Iraq.

The sons of the Labour left appeared to be playing out a glib aphorism often (and probably falsely) attributed to Winston Churchill: “If you’re not a liberal when you’re 25, you have no heart. If you’re not a conservative by the time you’re 35, you have no brain.” Soon enough, Barack Obama brought a similar trajectory to American politics. He described his intellectual awakening as a student in Dreams from My Father:

To avoid being mistaken for a sellout, I chose my friends carefully. The more politically active black students. The foreign students. The Chicanos. The Marxist professors and structural feminists and punk-rock performance poets. We smoked cigarettes and wore leather jackets. At night, in the dorms, we discussed neocolonialism, Franz Fanon, Eurocentrism, and patriarchy. When we ground out our cigarettes in the hallway carpet or set our stereos so loud that the walls began to shake, we were resisting bourgeois society’s stifling conventions. We weren’t indifferent or careless or insecure. We were alienated.

Obama’s background as a community organizer and activist gave way to appeals to bipartisanship and compromise, under a patina of progressivism. “When classmates in college asked me just what it was a community organizer did,” he remembered, “I couldn’t answer them directly. Instead, I’d pronounce on the need for change.”

If ’60s-era radical activity threw the American political balance off-center, it did not quite manage to create a different society; the new could not be born. An aggressive shift back towards the middle shifted the center rightward, pushed to the outer limits by Reagan and George H.W. Bush. We are still reeling from the consequences, with the last two Democratic administrations giving way to increasingly reactionary successors. In a time in which rising global violence, unprecedented inequality, and the tangible threat of apocalypse demand drastic action, certain members of the Democratic Party — like Buttigieg and Harris — remain committed to maintaining the status quo.

Near the end of the pilot episode of Family Ties, Alex is headed to a party at a country club, in a bid to win the affections of the scion of a wealthy local family. His parents are crestfallen. The place he plans on going is a “restricted” club, his father tells him. As his mother explains, it’s an institution that “doesn't have any members that are black or Jewish or Hispanic or any other group that didn't come over on the Mayflower.” They urge him not to go. Alex, however, is unfazed.

“I just want to go to a party, mom,” he says. “I don’t want to change the world.”