There are plenty of familiar metaphors for politics — a swamp, a circus, a schoolyard — but John Kass, an opinion columnist at the Chicago Tribune, has come up with a new one. In a recent column, Kass describes the Democratic party as an organization of singing derelicts in an edible fantasy land. He writes that hearing Democratic presidential candidates discuss their platforms is “like staring from a distance at the Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

“The Big Rock Candy Mountain” is a well-known and well-loved folk song, written at the turn of the 20th century by songwriter and poet Harry “Haywire” McClintock and sung from the point of view of a wandering hobo. The hobo imagines a world less harsh than our own, where instead of sleeping on the street and riding the rail he rests in an idyllic utopia. Kass quotes part of the first verse, which goes:

Where the boxcars all are empty

And the sun shines every day

On the birds and the bees

And the cigarette trees

The lemonade springs

Where the bluebird sings

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains

Kass calls this an encapsulation of “Democratic economic policy,” a program he sees as being “written for modern Americans who’ve been trained to despise the freedom offered by capitalism, while yearning for free stuff promised by the federal masters.” But our intrepid pundit is not so easily lured in. “I concentrated on what the candidates were saying,” Kass writes, “and it completely harshed my mellow.” The Big Rock Candy Mountain is just a fantasy.

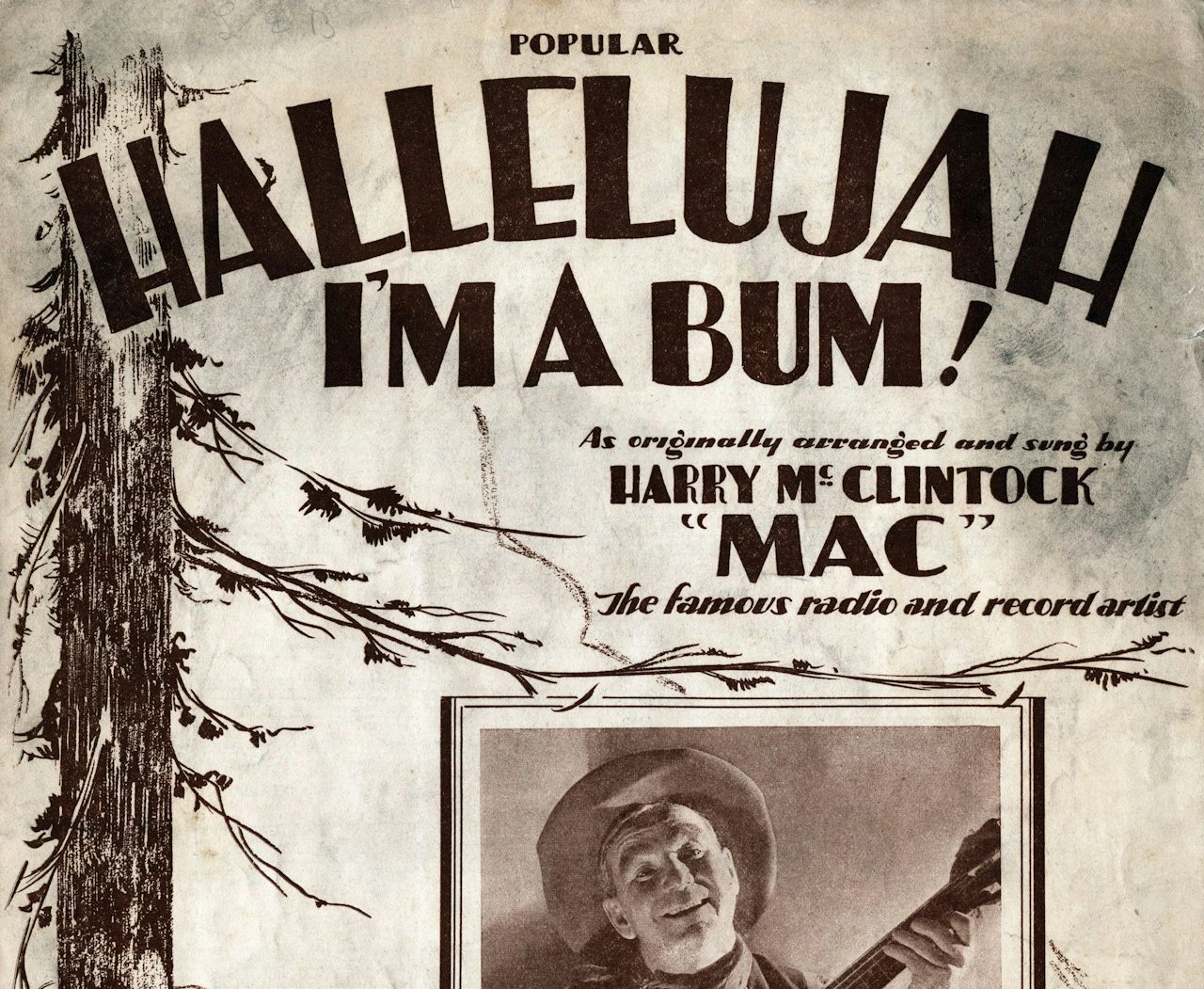

In the technical sense, this is true. But even a fantasy comes from somewhere. In the case of the Big Rock Candy Mountain, it came McClintock, a man who did indeed live as a hobo and also wrote the song “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!” But there was more to McClintock’s story. He was a union organizer who worked on oil fields in West Texas, and a lifelong member of the Industrial Workers of the World, a labor union founded at the turn of the century. It was not a politically neutral organization, and its revolutionary orientation was summarized in its constitution, which called for “abolition of the wage system.” Setting out to become “One Big Union,” the IWW included miners, textile workers, and farmworkers alike. Its founders included Eugene V. Debs and Mother Jones. Members were colloquially referred to as “Wobblies,” a fitting sign of irreverence and humor that characterized the organization’s rhetoric.

One of the IWW’s greatest legacies is its songs, of which “The Big Rock Candy Mountain” is an unofficial example. The core canon, meant to be sung on shop floors during strikes and streets during marches, is collected in a pamphlet called The Little Red Songbook, first published in 1909. Its influence is wide and varied — a young Leonard Cohen, at Jewish community camp, learned to write songs from studying its contents, and its best-known song, “Solidarity Forever,” remains the anthem of the American labor movement. Those unfamiliar with this body of work should immediately seek out Utah Phillips’s recording of IWW songs, We Have Fed You All for A Thousand Years.

For the songs to function effectively for a multiethnic, multilingual labor movement, they had to be easy to understand and sing. So they were plagiarized from more familiar melodies; as Phillips puts it, “the wobblies liked to steal the hymn tunes because they were pretty, and change the words so they made more sense.” But they were more than propaganda; many of them, like “Bread and Roses” or McClintock’s work, deal with less straightforward questions of what makes a good life.

Many of the most famous songs in the collection were written by Joe Hill, a Swedish immigrant and itinerant worker who was executed in 1915 for the murder of a policeman. He was almost certainly falsely accused, and the trial was so corrupt that even President Woodrow Wilson opposed his verdict. One of Hill’s songs, “The Preacher and the Slave,” is the origin of the expression, “pie in the sky.” The song was first performed by McClintock and some co-conspirators, under circumstances Utah Phillips describes on record:

They got together a little band: T-Bone Slim, a tuba, a garbage can lid. They stood in a doorway, waiting to leap out at the unemployed throng and regale them with song. They used a shill to build the crowd. You know, a carney shill, somebody who uses tricks to build a crowd? His name was Tresca, but he wore a black suit, a black bowler hat, and a string tie with an umbrella and a briefcase. Looked like a banker. He walked down where they were hiding in the doorway and suddenly he started to yell: “Help! Help! Help! I’ve been robbed! Help! I’ve been robbed!” Everybody’d run across the street: “What’s the matter? What’s the matter?” As soon as he got the crowd together he yelled: “I’ve been robbed by the capitalist system! Fellow workers…” He talked to them for 10 minutes and then the boys would leap out and start singing.”

“Pie in the sky” has become an expression often used to malign political programs that seek to provide for the working class and the poor; the kind of politics John Kass dismisses as a fantasy. But the song itself describes quite the opposite. Joe Hill mocked the promise of religion, that a life of poverty would lead to redemption and comfort in heaven after death. “Work and pray, live on hay; you'll get pie in the sky when you die,” says the preacher, all the while collecting money from working people. But the song ends with the workers of the world uniting. Rebuilding society, they enlist the grifting preachers to serve the workers instead, cooking and chopping wood. As IWW founding member Big Bill Haywood put it, “nothing’s too good for the working class.” Perhaps John Kass should grab a pot and pan.