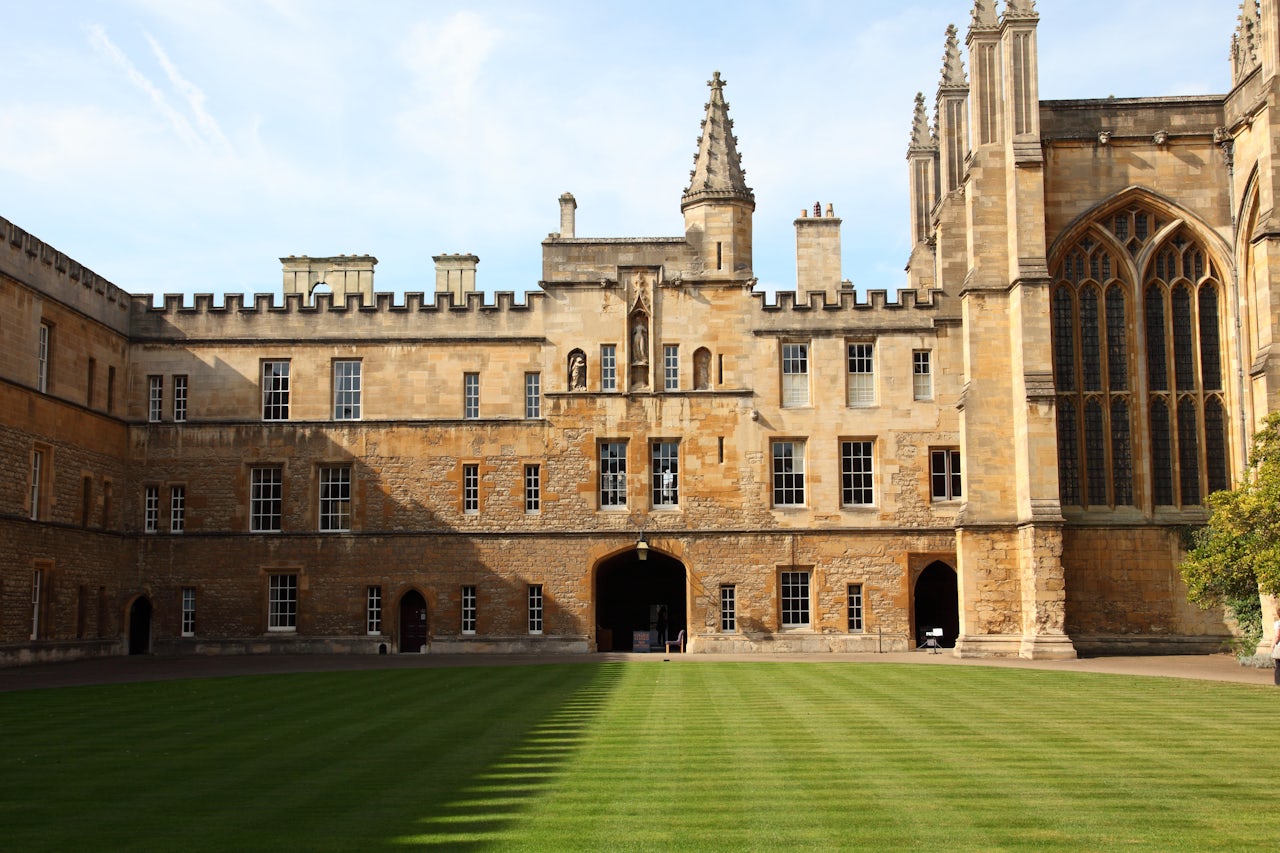

In 1999, I went to Oxford to start a degree in English and Modern Languages. I was a third culture kid, born in Boston with an American father and a French mother. The previous year, JK Rowling had published the first book of the Harry Potter series. I’d never heard of it, nor even read Brideshead Revisited, and I didn’t know anyone who’d studied there. Oxford, to me, was medieval stone, green lawns, and the glossy faces in the university brochure. It was a vague and exciting step on the road to whatever came next — what, exactly, would surely become clear. I was woefully ignorant of the myth and the magic of the place: the storied alumni, the revelry, the formal dinners where you recite poetry dressed up in college gowns, or the university’s reputation for shaping the upper tiers of British society, to which I didn’t belong.

Midway through my first week at Oxford, I met Oliver. Oliver lived down the hall in the newly renovated west wing of our college that smelled of dust and wood glue. He was in Politics, Philosophy and Economics, the course of study for future prime ministers and hedge fund managers, and he didn’t directly talk about his money, but he let us understand that he’d had the best education and his father owned an enormous place in Scotland. He’d been the youngest accredited goldsmith in England at age 13, he said, and his oil paintings were on show in a gallery in London. His hobby was nouvelle cuisine; he invited me to a five-course meal he prepared on the electric stove in our cramped hallway kitchen. There were consommés and caramelized carrots and at the end he served chocolate almonds he’d bought from a London boutique.

Oliver’s stories about his lifestyle and his megabucks sounded too good to be true and I suspected they were. But when I googled him, he mostly checked out. Why would someone like Oliver befriend someone like me, an interloper from the American middle class?

Oxford and Cambridge are two of the oldest universities in the world and centers of the arts and sciences whose influence extends far beyond the reaches of British society. JRR Tolkien wrote The Hobbit while he was a professor at Oxford. The structure of DNA was discovered in a lab in Cambridge. Both are in the radius of London, Oxford to the west, Cambridge to the north, medieval market towns that were gradually taken over by the university communities. Their fame and prestige attract ambition of all kinds: intellectual, creative, political.

I met plenty of students with family money and elite bona fides. Much later I realized Oliver wasn’t one of them. He was something else, what one of our fellow first years dismissed as “new money.” He wasn’t a liar or a scammer, probably, but a first-class bullshitter.

Harry Frankfurt, in his essay “On Bullshit,” defines it as a kind of intellectual sleight of hand that is distinct from lying. “Someone who lies and someone who tells the truth are playing on opposite sides,” he writes. The bullshitter is playing a different game altogether: bluffing, embroidering, hiding their true purpose, pulling the wool over our eyes. They dazzle us with their liberal displays of truthiness, indifferently serving up gems of fact with the glitter of fabrication. The bullshitter’s “only indispensably distinctive characteristic is that in a certain way he misrepresents what he is up to,” says Frankfurt. “He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.” A lie at least has a relationship to the truth: it can be argued with or debunked. Bullshit makes truth irrelevant.

Frankfurt doesn’t like bullshit, calling it “a greater enemy of the truth than lies are.” Yet it is integral to how we experience and construct social life, and it is the rich manure in the field of influence.

You can’t understand Oxbridge or, to an extent, Britain, without understanding bullshit.

Like all organisms that occupy the same uterine ecosystem, Oxford and Cambridge are rivals and allies, sharing common genetic material, competing for resources and prestige.

People tend to refer to Oxford and Cambridge in the same breath because they are two of a pair, mirror image homozygous twins, whose history is closely intertwined. Like other early European universities, they started out as Catholic institutions, training clerics and church lawyers. The Oxford clerical studium traces back to 1096. Cambridge was founded a little over a century later, in 1209, when a group of scholars left Oxford after a scandal involving a murdered woman and a dispute with the town authorities.

Like all organisms that occupy the same uterine ecosystem, Oxford and Cambridge are rivals and allies, sharing common genetic material, competing for resources and prestige. They share a collegiate system and many of the same college names: Jesus, Magdalen, Queens, St Catherine’s, St John’s. They share variants of the same rituals and rites of passage, like the May Balls, carnivals of extravagant consumption. They have their own architecture, their own vocabulary: pigeonholes (for mail), scouts or bedders (the college cleaning staff), bumps (rowing races). Speaking the language and taking part in the rituals is what you do to inscribe your existence into the cosmology of Oxford and Cambridge. They are — as the marketing brochures would say — world class centers of learning, rightfully proud of their outstanding pedagogy. At Oxford, I learned about New Historicism from Terry Eagleton, and Helen Barr, an expert on 17th century literature, patiently put up with my try-hard essays about moral ambiguity in Titus Andronicus.

Over the centuries, wealthy upper-class families, “the landed gentry, successful urban lawyers and medics,” started sending their sons there to get a classical education, says Laurence Brockliss, author of The University of Oxford: A Brief History. The trend really took off in the Reformation, when Henry VIII had his son and daughters classically educated. It wasn’t enough to be rich and powerful any more: you also had to know Greek. The lay elite “might not have worked very hard. Many of them were pretty feckless and uncommitted. Nonetheless, they picked up, whether beforehand or at university, a very good classical education.”

One of these students was George Gordon, Lord Byron, whose time at Cambridge became the basis for his enduring literary celebrity. The rules said he couldn’t bring his pet bulldog up with him to college, so as a giant fuck you to the rules, he bought a live bear and kept it in his rooms on a chain. He spent a lot of his time fucking, drunk, or fucking drunk. His mother blamed it on the Cambridge influence. When he left, he took the bear.

Four centuries later, British newspapers regularly examine the question of who attends Oxford and Cambridge: what percentage are women, state school, and BME (black and minority ethnic) students. The universities tally numbers and put out press releases where the message is, we’re no longer just for the elite. We’re fair. 18.3 percent of the England and Wales population aged 18 to 25 is BME, according to census data. In 2018, the proportion of BME students starting at Oxford was exactly 18.3 percent.

Yet they are still closely associated with the spheres of power and influence in British society, electric lines coursing under Westminster and Bond Street. It’s hard to find a British politician or mergers analyst over 40 who didn’t go to Oxford or Cambridge. Current Prime Minister Boris Johnson read Classics at Balliol College, Oxford, like Prime Ministers H. H. Asquith and Harold Macmillan before him (same major, same college).

In a culture of bullshit, the greatest sin is to mean what you say.

The infamous party culture has survived stubborn efforts to democratize the university. It thrives in a variety of rarefied clubs, Great Gatsby on the Cherwell, a potlatch of extravagant consumption. If anything, it now looks like a parody of itself. A biography of former Prime Minister David Cameron published when he was in office claimed that he had done something unspeakable to the head of a pig carcass during his days at the Bullingdon Club, an elite Oxford drinking society. The story was embarrassing and credible, coming as it did from Lord Ashcroft, Cameron’s friend from Oxford and a familiar figure in British politics. Plus, it sounded like the kind of thing you’d expect the toffs to do when no one was looking.

At Oxford and Cambridge, “jolly boys” like Cameron and Johnson partied and made connections. But alongside everyone else, they also trained extensively in the art of bullshit. Johnson made President of the Oxford Union debating society, where you won “not by boring the audience with detail, but with jokes and ad hominem jibes,” writes Oxford graduate Simon Kuper. Coming from a British public school background, they were ahead of the pack.

In a culture of bullshit, the greatest sin is to mean what you say. The greatest achievement is a state beyond truth or lies, where you can pluck out facts to suit your purpose while obscuring the greater context. It’s a universal wrench in the toolkit of the politician or any other ambitious soul who seeks to exert influence. In many ways, Johnson’s entire career has been about bullshit, like the stories he wrote bashing the European Union when he was a journalist for the Telegraph: “Italy fails to measure up on condoms,” said one story implying that Italians had smaller penises, a garbled fever dream that wilfully misinterpreted the safety concerns of Italian scientists.

Being good at bullshit allows you to reveal what you truly believe without being held accountable. Johnson has a long history of making remarks that would sink a more honest man. He once referred to African children as “piccaninnies” in the Daily Telegraph; the people of Congo, he added, would “break out in watermelon smiles to see the big white chief” Tony Blair, who was then visiting the country. He called gay men “tank-topped bumboys” and more recently said that Muslim women who wear the niqab look like bank robbers and letter boxes. Confronted about remarks like these, his defense is generally to say they were “satirical” or taken out of context. Johnson wants us to think that anyone who holds him accountable is a nerd, a loser who isn’t in on the joke.

Bullshit doesn’t always come in the form of words. It’s a holistic praxis that transcends semantics. Johnson’s trademark floppy hair is a prime example of bullshit. He’s known to muss it up before public appearances. Photos from his Oxford days show a carefully combed fringe that stays in place even when he’s roaring drunk. Look at me, says the floppy hair, I’m harmless. With hair like this, I couldn’t possibly subvert democracy in my selfish thirst for power.

In my classes at Oxford, there was fierce competition to have the cleverest lines while at the same time appearing to do the least amount of work. There were books to read and essays to write about a succession of new subjects that we were supposed to speak about with mastery and confidence. We would rarely admit that we hadn’t read or heard of something extravagantly obscure. For Modern Languages, every week for a year, we had 10 to 15 minutes to prepare a five-minute presentation on a theme assigned on the spot. It was a military education in the rhetorical arts. Handed a topic, you learned to bluff your way through anything, even if it made you sweat. Lack of panache in the execution was a sign of a weak character.

If you graduate with these skills, you can put them to any number of uses. A video of Boris Johnson that went viral over Christmas is a perfect illustration of this. Taken from his appearance on an Australian talk show six years ago, when he was still Mayor of London, it shows him laughing and joking with the audience before breaking out into Ancient Greek verse. He goes on for over a minute and a half, arms akimbo, gesturing and thrusting a confident finger to the gods. As Twitter users were quick to point out, Johnson runs roughshod through a mish-mash of poorly pronounced passages and skipped lines. His accent remains energetically British throughout, the Iliad as performed by James Corden in Cats. It’s the kind of trick you pull to impress people at parties, but it’s also a way to “distract from his real cultural and political vandalism,” says Charlotte Higgins, who, like Johnson, studied Classics at Balliol College. It is a tour-de-force of bullshit.

Wow. Whatever you think of Boris Johnson’s politics, reciting the Iliad in Greek is applause-worthy. (ht @Holbornlolz) pic.twitter.com/IjF6NfQxqe

— ian bremmer (@ianbremmer) December 24, 2019

It would be wrong to say that Oxford created Boris Johnson. But Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (the “p” is silent) certainly leveraged his experience at Oxford to create the character of Boris Johnson. In this way, he is not unlike Caroline Calloway, who planned her experience at Cambridge as a springboard for literary fame.

There are not many corporations or even countries that have lasted continuously as long as Oxford or Cambridge.

Before she arrived, Calloway created an account called @adventuregrams, purchased followers, and bought ads on Harry Potter fan websites. Promoting the memoir that was never written, she showed interviewers around the playing field of her enchanted existence: medieval stone buildings, notes in pigeonholes and sunsets over the river Cam.

There were many truths in her story. It’s just that the truths were carefully chosen to obscure the context. The augmented reality, the sparkle and magic of Cambridge, were there in the foreground, hiding the pills and the grime and the ghostwriter.

Calloway, who is open about this past and doesn’t shill diet teas, has been rather unfairly called a scammer. But her brand of life writing is part of a long tradition that transforms the writer’s existence into a living, breathing oeuvre in the shadow of the great universities. She is a master in the broad and subtle art of bullshit.

There are not many corporations or even countries that have lasted continuously as long as Oxford or Cambridge. Aligned with noblemen and kings, they could have fallen with their patrons over the centuries. They survived the War of the Roses, and later, the radical transformation of the British educational system. And as Brockliss told me, they are now undergoing a new shift, becoming international institutions on the global stage.

Their ability to evolve, through multiple forms, speaks to the nature of influence itself. Beyond academic institutions, Oxford and Cambridge are brands that reproduce themselves in and through their members. The brand, Brockliss said, “is very important for the university as a fundraising institution.” They are elastic and complex enough to accommodate figures like Boris Johnson and JRR Tolkien, academic heritage and elite debauchery. They absorb their most scandalous alumni: Byron was a marble statue in Trinity College, Cambridge, only 21 years after his death.

“Six years after I arrived at Cambridge as a freshman for the first time I am in L.A. selling the screen adaptation of that story,” wrote Caroline Calloway earlier this year. “[I]t’s exciting to think that next October 5th I could be back in Cambridge, an Executive Produce [sic] on the set of the life I once lived, branded, dismantled, rebuilt and sold.”

Her story might be filmed in Cambridge or, she says, Oxford as a backup location. They’ll tell the story of the darkness behind the glowing Instagram filters. They’ll still sparkle. They’ll still be written into the rich tapestry of bullshit.