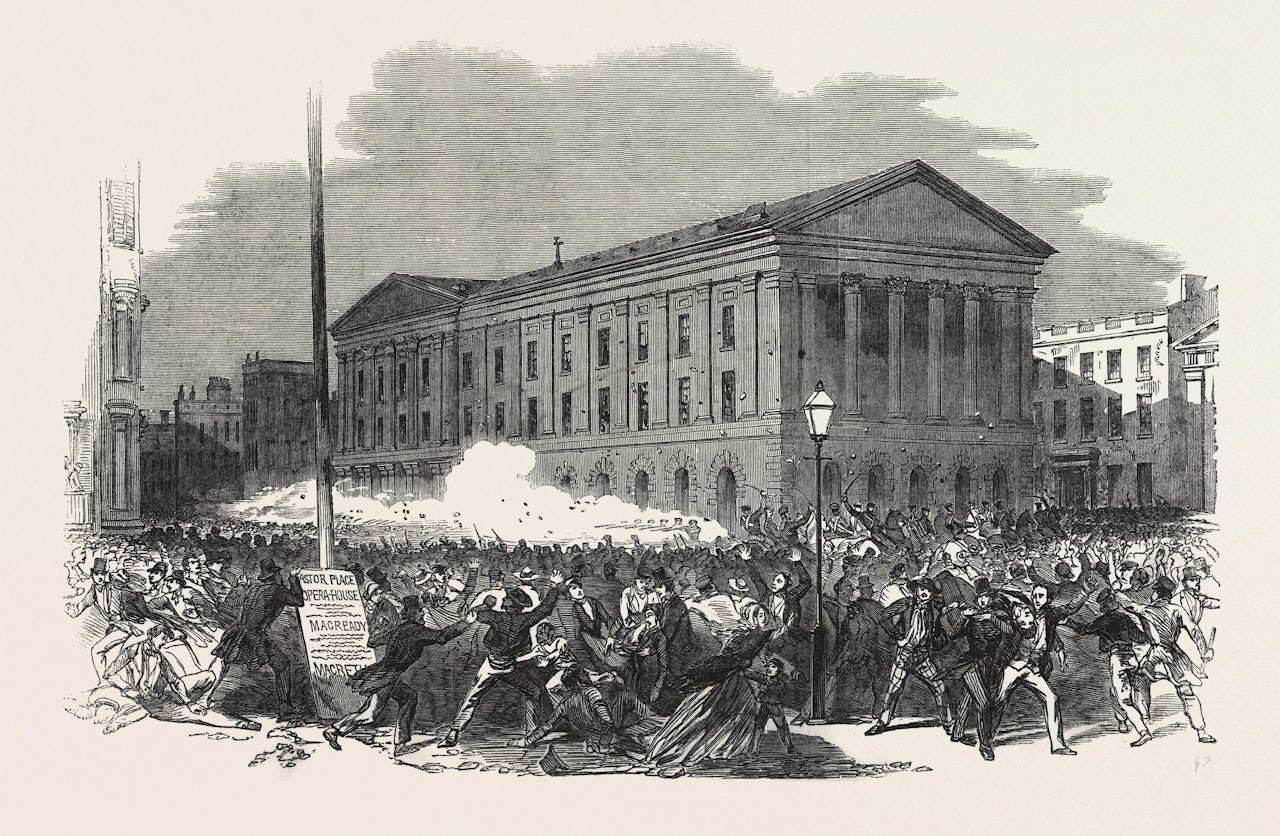

If you ever find yourself walking in Astor Place in downtown Manhattan you might notice a plaque, really more of a laminated sign, tucked in the window of one the new skyscrapers between The Bowery and Lafayette Street. The sign, which is maybe only 18 by 24 inches, reads ASTOR PLACE RIOT with a 19th-century lithograph of a vast crowd menacing a neoclassical building.

In the foreground, one can see individuals in various poses suggesting alarm and outrage, or else lying on the ground, wounded. In the distance, you can see the faint outline of troops, with illuminated clouds of smoke dancing above their heads. This modest poster, so easy to miss in the hubbub of the square, is the only memorial on the spot of an event that endlessly fascinates me: The Astor Place Opera House Riot of May 10, 1849.

There’s something both grimly funny and profound to me about the riot; it seems to express the madness of American history. A mob of thousands attempted to storm a theater over a performance of Macbeth, the National Guard had to be called up, 31 people were killed and more than 100 wounded all over the personal jealousies of two vain and insecure actors, an Englishman with aristocratic airs named William Macready, and an American, Edward “Ned” Forrest, who seemed to his audiences to embody a new democratic energy.

The dispute between Macready and Forrest is such a labyrinth of prickliness, petty slights, and paranoia that it’s hopeless to try to recount in detail, but I’ll try to briefly summarize it. Forrest had previously hissed at a performance of Macready’s in Edinburgh, which he later proudly admitted in a letter to a newspaper. Forrest believed that, in revenge, Macready had deliberately set the English press against him and damaged his career there. In any case, neither of them comes off well in the incessant letters lambasting each other that were published in the newspapers in both countries.

By the time he arrived in America for his performance of Macbeth, a considerable section of the public had turned against Macready, especially those in the working class, who despised anything fancy and British, although they still loved Shakespeare. That same public was also ill-disposed to the venue he was to play. The Astor Place Opera House had been built specifically to bring European high culture to New York and it required attendees to have clean shaves and kid gloves. Sitting just off the top of The Bowery, where a Starbucks now resides, it looked superciliously down at the more demotic theaters that dotted that row.

Forrest also happened to be acquainted with a downtown ward boss named Isaiah Rynders, a former gambler who made his living running saloons and brothels and wrangling Irish votes for the Democrats, and one E.Z.C. Judson. A former sailor, Judson had seduced a man’s teenage wife in Tennessee, killed the man in the ensuing duel, and then was set upon by an outraged mob and lynched, only to be cut down by a passerby. He made his way to New York, where he took up the profession that seems to attract such low sorts sooner or later: journalism. He ran a scurrilous rag that played on nativist themes and wrote plays that pandered to the tastes of “Bowery B’hoys,” as the dandified proletarian ruffians who roamed downtown streets spoiling for fights were called.

Though Judson and Rynders were ostensibly political rivals — the former an anti-Irish nativist and the latter leaning heavily on the Irish for votes and muscle, hatred of the English united their constituencies, which were at other times quite literally at each other’s throats. Forrest is known to have met with both Judson and Rynders prior to the affray at Astor Place, and if he did not exactly conspire with them, he at least gave his tacit blessing to their designs.

There’s something both grimly funny and profound to me about the riot; it seems to express the madness of American history.

When Macready’s Macbeth opened on May 8, Rynders arranged for 50 tickets to be given to his friends, with the idea that they disrupt the performance. Up high in the balconies, they threw rotten eggs, potatoes, and a bottle of a foul-smelling substance called asafetida at the stage, and made so much noise no one could hear the play. When this failed to stop the performance, they resorted to throwing chairs. Eventually the play was called off, and Macready left the theater to the raucous cheering from the balcony.

The remainder of Macready’s performances were to be canceled, but the upper crust of New York society, including John Jacob Astor and Washington Irving, organized a petition to persuade him to stay, so that not all American would be ranked with the barbarous multitudes. Macready decided to stay on: Macbeth would return to the stage that Thursday, May 10. Now it was Judson’s turn to go to work. All over the city, handbills began to appear featuring the question, “WORKINGMEN — SHALL ENGLISH OR AMERICANS RULE THIS CITY?”

The new Whig mayor, Caleb S. Woodhull, was determined to defy the mob and arranged for hundreds of police to guard the theater. He also called on the New York State Militia to muster several companies a few blocks south of Astor Place in Centre Market. By 7 p.m. a crowd of nearly 15,000 people had packed the square. Once the show got began, demonstrators in the upper tiers of the opera house started to make such a racket that they had to be stopped periodically.

During intermission, the police arrested a few of the rowdiest offenders in an attempt to make an example of them. The newly arrested were put in a room underneath the stage, where they tried to light a fire. A rioter inside managed to poke his head through a window to inform the crowd outside that their confederates had been locked up. Around the same time, a police officer in the lobby stuck a hose through one of the windows and began to spray the crowd in Astor Place. At these provocations, the mob went berserk. A sewer had recently been dug on Lafayette Place, and the unearthed paving stones provided a ready supply of missiles to use against the theater and the cops.

Somehow, even though under the constant barrage of paving stones, the play managed to continue inside. By 9 p.m., though, with the police taking heavy casualties and their lines in danger of being broken, the police chief and mayor decided to resort to the militia. The troops attempted a bayonet charge into the crowd, but it was too tightly packed, and rioters managed to wrest muskets away from some soldiers. The commanding officer gave the order to shoot over the rioters’ heads as a warning, to no effect. Finally, the order was given “fire low.” The mob retreated and continued to throw paving stones at the troops, until the militia threatened to use artillery on them, after which the crowd finally dispersed, leaving behind them a scene of carnage. The promise of further violence was suppressed by the heavy presence of troops, who migrated west to Washington Square and turned the park into an armed camp.

The Astor Place riot combined two of 19th-century America’s favorite pastimes: going to the theater and rioting. This was especially true in the period after the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828, who was swept into office on a wave of raucous populism and expanded suffrage to all white men. Jackson’s inauguration was very nearly a riot itself: a horde of drunken men packed the White House, destroyed furniture and overturned the food laid out. The crowd could only be lured onto the lawn with the promise that more whiskey-spiked punch would be served outside. The violence peaked in 1835, when the country saw some 147 riots, according to David Grimsted’s American Mobbing: 1828-1861: Toward Civil War.

Local elections were always at risk of descending into days of mayhem if the result was close or disputed. Protestants and Catholics were often at odds. Many riots were related to slavery: Southerners rioted in response to slave insurrection scares, Northern mobs attacked abolitionists and free black communities, and free blacks and white abolitionists rioted in order free captured fugitive slaves. But anything remotely exciting could whip up a crowd apt to go wild. In 1844, when Edgar Allan Poe published a hoax (fake news!) in the New York Sun that announced a man had crossed the Atlantic in a hot-air balloon in three days, crowds besieged the newspaper’s office in the hopes of getting a copy. In 1858, the ecstatic crowd celebrating the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph lit fire to the dome on City Hall with fireworks. That same night a separate mob, fearful of disease, stormed and burnt a quarantine hospital in Staten Island.

A certain amount of rowdiness among theater goers was tolerated and even understood to be a democratic right of the audience.

An evening at the theater, one of the only forms of popular entertainment available, with its large, often-drunk crowds excited by the drama on stage, was always at risk of falling into pandemonium. In 1825, the celebrated British actor Edmund Kean was greeted in Boston by a shower of missiles because it had been revealed in the newspapers that he committed adultery. Another actor, Joshua Anderson, had several performances called off between 1831 and 1832 because violent patriotic mobs objected to the presence of an English actor. (I would be remiss not to mention that the sheer amount of alcohol Americans drank in the era provided fuel for these public explosions. In 1825, the average American over the age of 15 consumed seven gallons of whiskey a year; workers punctuated their morning and midafternoon breaks with hard liquor.)

A certain amount of rowdiness among theater goers was tolerated and even understood to be a democratic right of the audience. As the author of a pamphlet describing the Astor Place Riot helpfully explains, “The public and magistrates have been accustomed to look upon theatrical disturbances, rows and riots, as different in character from all others. The stage is presumed to be a correction of the manners and morals of the public, and on the other hand, the public has been left to correct in its own energetic way, the manners and morals of the stage.” Freedom of speech was understood to extend both ways — to the audience and the players.

Reflecting on the Astor Place Riot, it’s hard to take seriously the frequently heard melodrama on the right and center that we are faced with such a high pitch of identity politics that the continuance of the Union is in doubt. Online mobs are one thing, but it’s good to remember appellation “mob” in that case is often more metaphorical than real. There’s also a lot of talk about decadence these days,, but if decadence makes us more timid than these rough creatures, then so be it. Call me soft, but I’m glad to be able to go to the movies without having to dodge brickbats. We seem to be in a period where crowds are reasserting themselves a bit, but can we even imagine great masses of men getting exercised about Shakespeare today?

The Astor Place Riot is also reminder that we’re still very much the same nation: riven by divisions over culture, class, race, ethnicity, and religion, divisions that can have passionate and violent expressions, especially when they are exploited by unscrupulous demagogues. But it seems to me the country will continue blunder forward, swinging from tragedy to farce and back again, and it will not always be easy to know which is which.