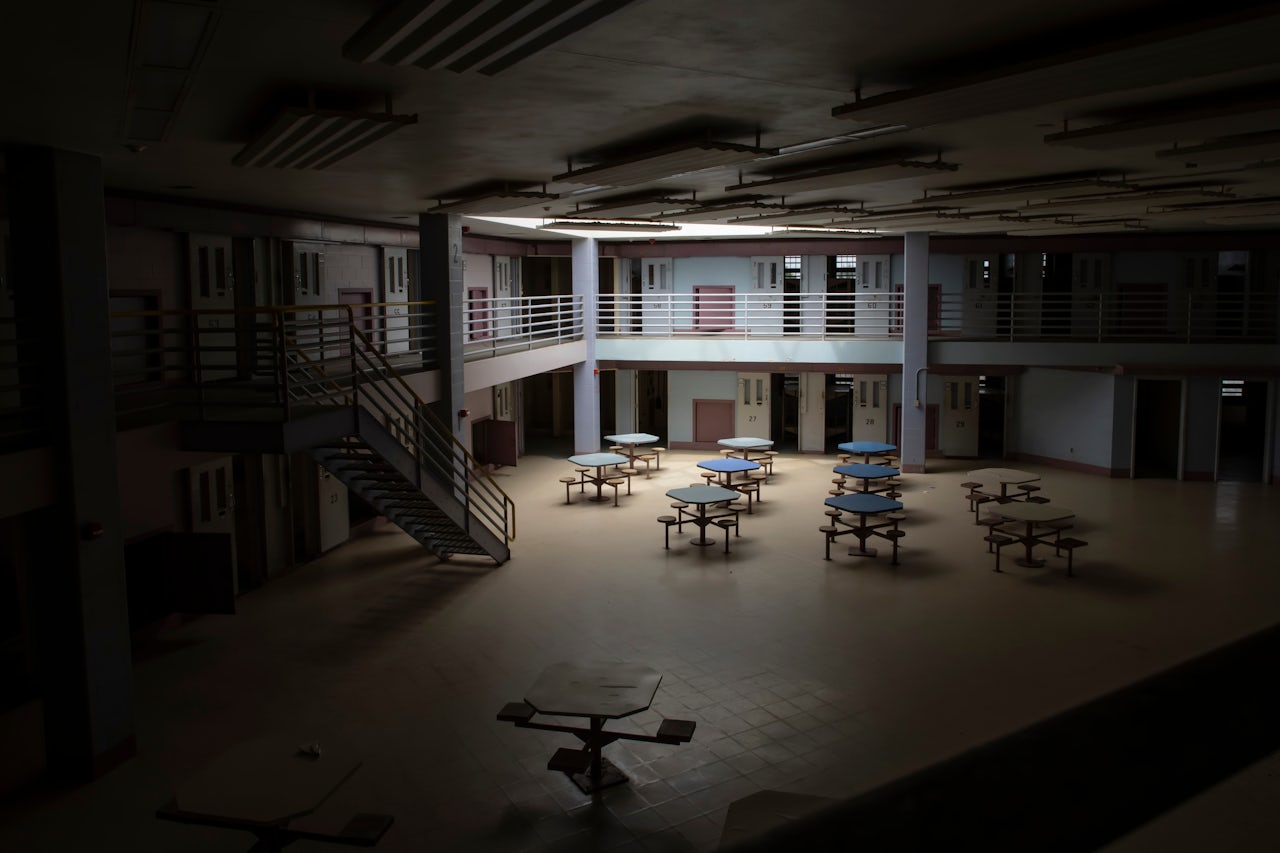

The coronavirus outbreak has grown from an isolated, regional health scare to a worldwide threat. However, health statistics, including those that come from the Centers for Disease Control, tend to overwhelmingly neglect one particularly at-risk population: the more than two million people in the United States held in prisons, jails, detention centers, and correctional facilities — often in alarmingly close quarters. After years of failing to mitigate the spread of infectious disease outbreaks, American prisons are faced with figuring out how they’ll prevent a coronavirus outbreak from sweeping their petri-dish-like conditions.

“The notion that these [facilities] are walled off and separate from the communities is just absolutely incorrect,” Dr. Homer Venters, who heads the nonprofit Community Oriented Correctional Health Services and is the former chief medical officer for the New York City jail system, told me. “There's an active flow of people in and out every day.”

Venters has worked on mitigation efforts for several infectious disease outbreaks in detention facilities, from seasonal influenza to H1N1. In an op-ed for The Hill last week, he highlighted some of the major red flags that he believes corrections officials need to address as the likelihood that coronavirus, or COVID-19, will infect those behind bars grows. “One of the central concerns I have is that correctional health systems are built to take care of one patient at a time,” he said. “They don’t have the capacity generally to take a population health approach.”

The incarcerated population is more likely to have asthma, heart disease, and other conditions that increase the risk of catching even a mild virus.

Those who are detained or work in prisons and jails are at high risk of communicable disease due to a number of factors. Since 1970, the prison population has grown by 700 percent. According to the ACLU, facilities have struggled to keep up, and as a result many prisons across the U.S. are overcrowded. On top of that, access to and quality of medical care is dependent on state budgets, and thus varies greatly from state to state. “It’s a very fragmented system,” Venters said.

And the care that is available usually isn’t free. In most American prisons, inmates have to fork up a copayment to see a doctor. The up-front cost stems from the Social Security Act of 1965, which excludes inmates from any federal Medicaid funds unless they’re hospitalized for more than a day. The responsibility for paying for an inmate’s care ends up on the state, the county, and the inmate themself. But just like it is for many Americans, a copay is a huge barrier to care for those behind bars, and many simply forgo seeking care at all. “Our prison system is not interested in making sure everybody gets the best possible care,” Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson for the criminal justice non-profit Prison Policy Initiative said. “People in prison are treated as disposable.”

Inequity in prison medical care has actually led to inmate deaths in past virus outbreaks. In 2017, an Oregon prison allegedly purchased only 519 flu vaccines for an inmate population of 1,645. Only 300 vaccines were actually used, primarily on inmates who were already showing symptoms of the flu or who asked for the vaccine. The lack of vaccination and slow response to treat symptomatic inmates allegedly contributed to the death of 53-year-old inmate Tina Ferri, whose family filed suit against the prison in 2018. Several inmates who were held at the same time as Ferri testified that they weren’t even aware the vaccine was available to them. During an H1N1 outbreak at a Texas prison in 2016, an inmate infected with the flu died from secondary pneumonia. His illness was worsened by complications from MRSA, an antibiotic-resistant staph infection that is also common in prisons.

The constant flow of both staff and detainees in and out of jails means that a powerful virus could take over quickly and easily. “Any outbreak that's affecting the community is going to affect the jail,” Venters told me. “There's just no way to stop that. The jail is part of the community.”

But it’s not just poor conditions and lack of preparation that make prison and jail populations more susceptible to infection. The incarcerated population is more likely to have asthma, heart disease, and other conditions that increase the risk of catching even a mild virus. Respiratory illness in particular has been linked to coronavirus deaths. The prison population is also getting old; people over 55 are the fastest-growing demographic in U.S. facilities. And as the virus spreads, age is proving to be a serious risk factor for coronavirus severity. The first major analysis of China’s COVID-19 cases showed that people aged 50 and above have a disproportionately high chance of virus-related mortality, which increases steeply for each 10-year age gap. “Nevertheless, you have a health care system on the inside that’s not equipped, and honestly often uninterested, in treating the needs of that population,” Bertram said.

Venters said that while the CDC and America’s health care system at large have created a sophisticated structure for promoting prevention and surveilling outcomes of outbreaks like COVID-19, the efforts stop short of those in custody. “The structures that do that have really not been present, and have not cared — or have not yet been forced — to cast their eyes behind the walls of jails and prisons,” he said.

Counting coronavirus cases in the general population is already difficult, in part because some people will never seek care if they contract the disease, and because some who are infected will never show symptoms. The BBC estimates that most cases of coronavirus will not be counted at all. The virus seems to be moving faster than any reliable information on it. But this lack of information is, in itself, a systemic illness that the U.S. prison system has yet to shake. The Bureau of Justice Statistics hasn’t published general data on the total correctional population, which includes people on probation and parole as well as those in custody, since 2017. The CDC hasn’t collected comprehensive data on prison health care services since 2013. This ongoing lack of information will only make tracking and treating coronavirus cases in prisons and jails more challenging, Venters said. “One of the things that [the CDC] will feel pain about and we all will suffer from is that they don't, as a matter of course, pay attention to health outcomes behind bars,” he said, “and that's a real, central hypocrisy in how the whole health system of our nation is set up.”

“Our prison system is not interested in making sure everybody gets the best possible care.”

For all we know, coronavirus could already be inside a U.S. prison or jail. And if that’s the case, there’s not much that can be done. The state’s Department of Corrections in Washington, where most U.S. coronavirus deaths have been concentrated so far, told me that they’re following a “communicable disease, infection prevention and immunization program” that was last revised in 2015, and that new intakes are being screened for exposure. As of March 3, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation told me they have no known cases of exposure. The state, so far, has the highest COVID-19 case count in the country.

The infection of the incarcerated isn’t just an issue of human rights for the disenfranchised. That constant flow of people in and out that Venters mentioned creates a feedback loop. Sick people in jails and prisons bring their illnesses back to their local communities when they get out or when loved ones come to visit, Bertram said. “When prisons don't provide care in an adequate way,” she continued, “the communities that are hit the hardest and that are burdened the most are the same communities that were hit hardest by mass incarceration in the first place.”