On March 27, 1964, a 9.2-magnitude earthquake rocked Anchorage, Alaska, killing 131 people and causing hundreds of millions of dollars worth of damage to the surrounding area. The disaster, and the community effort to heal the damaged city, is the subject of This Is Chance!, a book by New York Times Magazine contributing writer Jon Mooallem, who sifted through thousands of documents and conducted dozens of interviews after beginning research in 2014.

The irony that his book’s publication date — March 24, 2020 — is in the throes of what is now a full-blown global crisis over the novel coronavirus is not lost on him, though in a roundabout monkey’s paw sort of way, it’s prepared him for the present moment. “I basically just spent six years picturing, or like even living inside, a disaster,” he told me. “And part of that means really understanding that more is possible than we think.”

Mooallem is just one of many writers who has a book release coinciding with what may be the worst non-electoral time to think about anything that isn’t current events since 9/11. So far, he and his publisher Penguin Random House have postponed nine dates of a planned book tour, echoing a nationwide trend as dozens of bookstores have shut down all of their events through at least March, probably April, and even beyond. Some of these dates will be rescheduled; many of them will not be.

Publication dates for books are typically set at least a year in advance; competing releases, promotional resources, anticipated current events, and many other factors taken under consideration. Rebecca Dinerstein Knight, whose novel Hex is out March 31, set her publication date nearly two yearsago when she sold the book. “They wanted it to be a springtime release, partly because the book is so occupied with the natural world,” she told me over email. The first four events of her tour were canceled, while one at the upcoming Loft’s Wordplay festival in Minneapolis will be conducted digitally. Rachel Vorona Cote, whose cultural history Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today came out February 25, said “there was some thought that early-ish in the new year was a good time for an author’s debut.” She ended up cancelling six events comprising the second half of her tour. Eric Nusbaum, whose baseball book Stealing Home is out March 24, was supposed to see his book coincide with Major League Baseball’s Opening Day on March 26. He canceled 10 events; Opening Day has now been delayed to at least mid-May.

Adrienne Raphel’s Thinking Inside the Box, which dives into the history of the crossword puzzle, was pegged to the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, the largest crossword tournament in the country. The tournament was set to take place March 20 to 22 — hence her publication date of March 17. “Penguin Press was even one of the sponsors of the tournament this year!” she said. “But gathering 700+ majority septuagenarians in a ballroom along the Northeast Corridor in the middle of a global pandemic is among the worst ideas ever.” The tournament has been rescheduled for September; Raphel has postponed six events, and is expecting to cancel more.

That such obvious logic — a book about crossword puzzles should come out while a giant crossword puzzle tournament is happening! — would be suddenly and violently upended by unexpected catastrophe mirrors the disruption that has now rippled through every facet of American life, such as the closing of movie theaters, the shuttering of bars, and the cancellation of national sports. Writers are famously pessimistic — Nusbaum said he began mentally preparing to cancel his events toward the end of February, long before any cities had been shut down — but there was no expecting this. At bare minimum, the years spent writing a book crescendo with the catharsis of release (if not instant acclaim and riches).

“I basically just spent six years picturing, or like even living inside, a disaster. And part of that means really understanding that more is possible than we think.”

Book events, which typically consist of a reading and a Q&A, are an expected payoff for most authors, an immediate way of connecting to people who, amazingly, have decided to spend time with your work. “The sales at the events are one thing — even vaster is the interpersonal energy, the word of mouth, the community building, the opportunity to meet and thank independent booksellers who bring the work into new hands,” Knight, who went on a lengthy international tour for her first novel, The Sunlit Night, that “created the book’s foundation,” said. “I wish I could share this work with old and new friends on the road, in person, with face-to-face connection.”

Mooallem got to do just one event for his book: a talk at the Oatmeal Club, a loose organization of seniors who meet for breakfast every Thursday morning at the Eagle Harbor Congregational Church in Bainbridge Island, Washington, where he lives. “I tweeted the night before that I was going to give it my fucking all, just in case it turned out to be the only time I got to do a book event,” he said. “Carpe diem.”

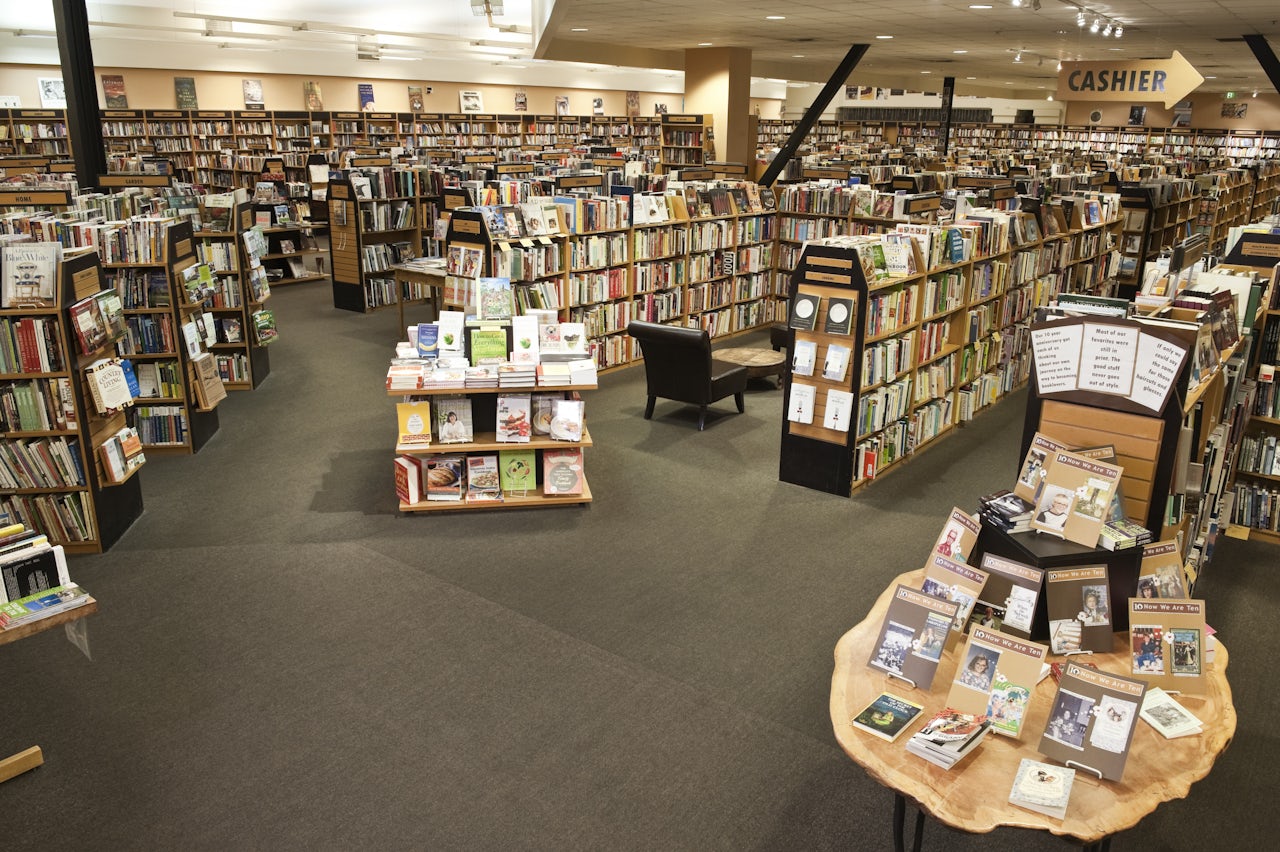

The best way to support authors whose events and tours have been felled by coronavirus remains the same — buy the books (or have your local library order it) and talk about them — but becomes more pressing. In particular, you can order from local bookstores if you don’t want to throw more money into Amazon’s maw. “Algorithms are wretched, but they impact so much: a book is more likely to be given exposure if it has numerous reviews (and of course it helps if those reviews are positive),” Cote said. “And thankfully, you don’t have to buy a book on Amazon to review it there.”

Beyond that, new releases and their events are just one public-facing chain of a publishing industry, like many others, now rocked by the ongoing events. Many bookstores across the country have closed their physical doors, with upcoming pay for hundreds of non-salaried booksellers contingent on federal intervention or, chilling, employer largesse. Others will be simply let go: On Monday, the New York bookseller McNally Jackson, which is currently facing a unionization effort, laid off more than two dozen employees. Some stores may survive the dip in income if legislation is passed or if they can transition to a digital-only model; others will not. Authors looking to sell a draft or proposal may soon face the extra burden of a financial recession. What books will anyone want to read in a year, if all the worst predictions come to pass?

As civic shutdowns become more common, and self-quarantine evolves from gentle suggestion to ongoing reality, everyone will need ways to stay occupied at home. Books aren’t more inherently meaningful than any other medium, but they do provide a unique respite of solitary reflection and internal engagement, from which everyone can benefit.

What books will anyone want to read in a year, if all the worst predictions come to pass?

And while any kind of reading can provide this pleasure, other works accrue specific relevance under present conditions. Over the week, my thoughts returned to Jessi Jezewska Stevens’ lyrical debut novel The Exhibition of Persephone Q, released March 3. Persephone Q is set in post-9/11 Manhattan and concerns a woman whose nude image has been digitally appropriated by an artist ex-boyfriend — or maybe not. The titular heroine wanders through a city whose social rhythms have been profoundly altered, something I thought about this weekend whenever I found myself on an unexpectedly empty street.

Stevens, who canceled six dates of a planned tour, didn’t want to draw any direct comparisons between her book and the crisis, but agreed there were some thematic parallels. “When I started writing the book in 2016, I had the ambition of filtering a national mood through an individual story,” she wrote over email. “The Exhibition of Persephone Q is focused on confusion around identity, propelled by the question of, Who am I, and who else might I be? But it’s also very much preoccupied with the collision of different answers to that question — and of different versions of the truth — and how unsettling, even violent, those collisions can be. … I think that feeling of having your own version of reality contradicted, of struggling to determine what’s true and what’s not, to separate good information from bad, feels very applicable to the COVID-19 crisis.”

Mary South, whose excellent short story collection You Will Never Be Forgotten (released March 10) often touches on how technology alters the dynamics of human connection, said “it is a bit eerie to me that I wrote a collection about disconnectedness and loneliness and the internet just as everyone has to self-isolate and live online. But just as there’s a lot of humor and tenderness in my stories — not just alienation — I’m seeing a lot of warmth online as people strive to support each other during this time. That’s the positive side of this situation.”

Of the writers I spoke with, Mooallem’s book was the most literally relevant, even as the shape of a pandemic is much different than a destructive earthquake. In a recent piece for The New York Times, he wrote movingly about the parallels: “Thrown all together, in one unrelenting present, we are made to recognize in one another what we deny most vehemently about ourselves: In the end, it’s our vulnerability that connects us.”

That piece was published on March 12, before some of the most dramatic coronavirus responses were announced. When I asked if his feelings had evolved in the days since, he said it still applies. “I’m not going in with a fear or distrust of other people,” he said. “I’m expecting good. I’m looking for good. I’m looking for togetherness.”