IT HAPPENED

is a series reflecting on our memories of 2017, one month at a time, as we head into the new year.

I was raised in the Christian church, and Revelation was my favorite book of the Bible. As a kid, I’d read it for the imagery: hellish monsters rising from the ocean, angels sounding trumpets at the edges of the earth, and the moon turning to blood as the forces of Good and Evil sparred one last time. The intrigue of Revelation is that these events are presented as an intentionally vague and symbolic vision, rendering them malleable as allegory for any events in mankind’s existence. War! Earthquakes! General confusion and chaos! Dueling morals! The business model of apocalyptic thinking is that the apocalypse is always and forever happening.

The moon turning blood red could be any lunar eclipse. The beast rising from the ocean could be the Loch Ness monster, a submarine during a world war, or Lady Gaga coming out of a swimming pool in the music video for “Poker Face.” But the framing of this vision is always binary. There is Good, and there is Evil, and one has to win. That duality has always existed, but it came to a head this year throughout American culture and politics. In 2017, nothing else crystallized the conflict in the way we process art like the announcement of the Academy Award for Best Picture, in which two of the frontrunners, La La Land and Moonlight, were as different as night and day.

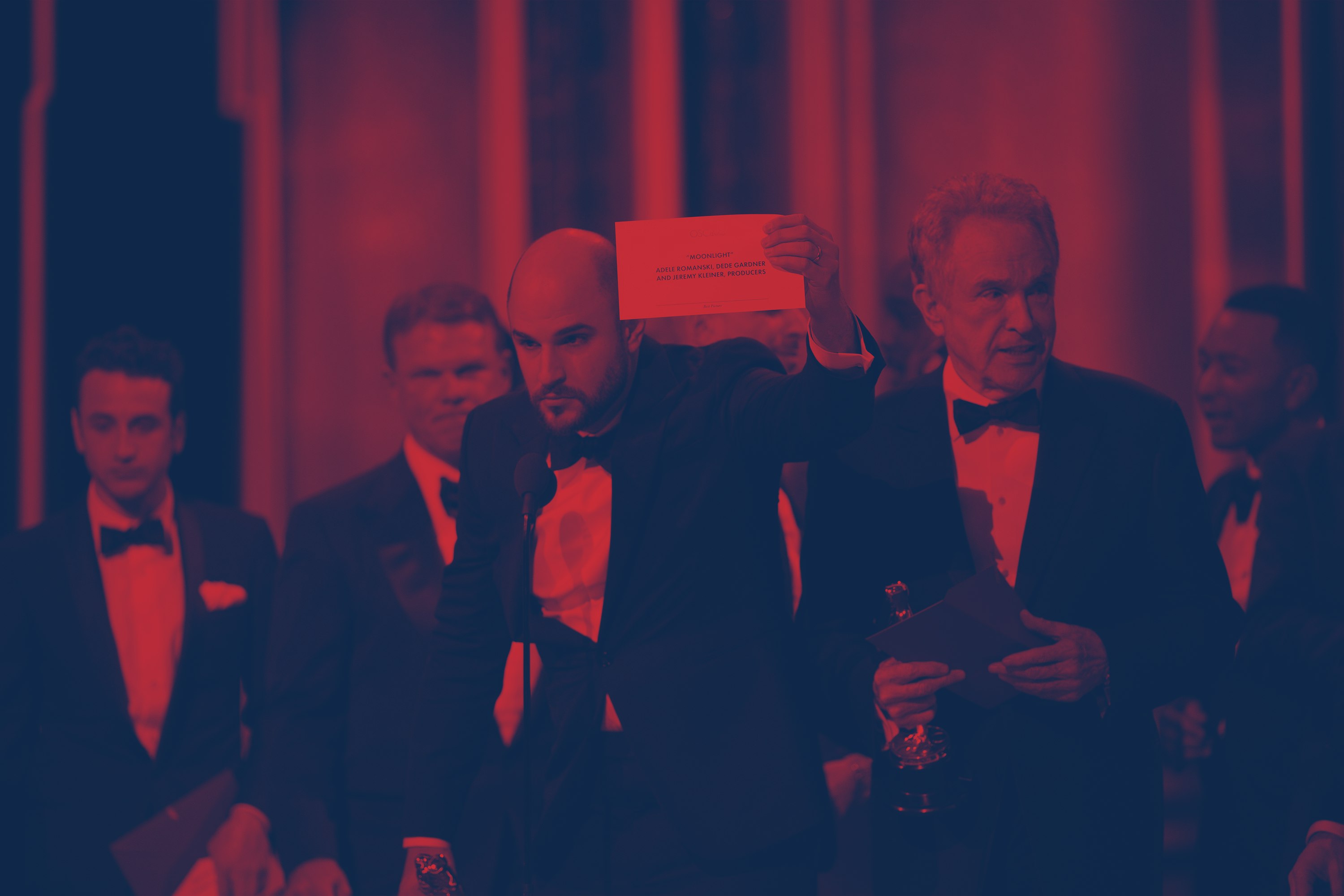

The moments leading up to the announcement felt biblical. For many people, La La Land winning would have been an affirmation of the status quo: a very white movie winning a historically very white award. Moonlight winning would have been the purest version of an underdog story — David defeating Goliath in the 11th hour; blackness thriving in the face of well-produced, “safe” whiteness. But there was no concerted trumpet for Moonlight when it was honored with the highest prize in cinema. Instead, the world was treated to a confused, shocking, unceremonious tuba when Moonlight won (after La La Land was incorrectly called up). It was as dark as it was refreshing and entertaining, as unfair as it was dizzyingly triumphant. The victory was clunky, the moment stolen.

The moment itself — when the mistake was realized — felt like a Renaissance painting. There was Damien Chazelle’s face, frozen with disbelief like a plaster cast of a Pompeii citizen gazing at Mount Vesuvius’s wrath. Matt Damon whistled. Jharrel Jerome picked up a tiny Alex R. Hibbert and they shared a breathless hug on stage. Nicole Kidman, Octavia Spencer, and Viggo Mortensen huddled nonplussed. And I shot up from my living room couch, clapped so hard that my hands went red, simultaneously attempted to reply to a barrage of texts, and happy-cried a little bit.

The weight of the meaning behind Moonlight taking the top award home started to eclipse its actual cinematic achievements for me. In my mind, Moonlight needed to win because it was a beautiful film that checked all the boxes that the Oscars look for in a movie, and did it in purely authentic, human, and gripping ways that soared above others that have taken the award in the past. It needed to win because a successful film about a black gay man and the world around him wouldn’t happen again anytime soon given Hollywood’s track record, and the images the movie produced were almost instantly iconic. It was a vessel for my own desire to see a story that resembled my life validated in front of the world.

I was also very prepared for it to lose. I grappled with a love I had of La La Land, which spoke directly to the theater kid in me and for all intents and purposes was a gorgeous movie that was fairly criticized for its white jazz narrative and faux underdog status, among other things. I found myself on two ends of an invented culture war as the public conversation shifted, and La La Land’s sunny veneer started to represent something more sinister. Please read the following question in Carrie Bradshaw narration voice: Could I still love La La Land while rooting for it to fail?

After seeing La La Land, at the height of the backlash, I went home and recorded an Instagram Story about how tormented I was about the movie. I was pretty sure I loved it. I thought the musical numbers were gorgeous. Ryan Gosling played piano extremely well, had a cute lil’ butt in his dress pants, and sounded forgivable when he sang. Emma Stone was an exquisite treat. The highway dance scene at the beginning made me giddy and excited to be alive. John Legend was in it, and he was very chill. But almost in real-time I let public perception of this movie, and how battle lines were being drawn with it on the “bad and potentially evil” side, influence my own very real, positive feelings about the experience.

Was there a “white savior of jazz” narrative? Kind of? But the movie also took care to highlight black musicians on camera while Sebastian (Gosling) ineffectively mansplained jazz’s roots to Mia (Stone) on a date. Important to note, however: those characters didn’t get to speak for themselves. Was it revolutionary? Not at all, but it succeeded in its attempt to modernize and pay homage to classic Hollywood musicals. Why was Seb held to a standard that his character on paper would not be able to live up to? And why would the flaws of the character, who is written as an undoubtable prick, dictate whether the movie is good or bad?

A lot of this has been litigated in public already. Justin Chang in the Los Angeles Times wrote that the “choice between La La Land and Moonlight has been framed as a choice between various opposites: whiteness and blackness, fantasy and reality, naivete and wisdom, appropriation and authenticity. But in the spirit of a less hostile, less Trumpian awards season, I’d suggest that these two fine movies, far from being natural adversaries, are in fact worthy companion pieces.”

We’re living in a time when platforms like Twitter and Rotten Tomatoes perpetuate an ecosystem of hype that gives unwarranted power to collective public opinion, as opposed to nuance. It’s become so obvious how we’re expected to react to backlash, and the backlash over that backlash. Somewhere in that gray area, it’s easy to lose sight of our own convictions as wildly different pieces of art are placed in conversation with each other. What is created instead is a panopticon of wokeness where expressing love for something with forgivable flaws aligns you with the Wrong Side. La La Land’s transgressions were not harmful in deeply tangible or profound ways, but they were made out to be. When it came time for awards season, saints needn’t profess their appreciation for it, lest they be branded with the mark of the beast.

Our metaphorical stakes can and should be lower. And awards do not need to change how movies and art make us feel. La La Land and Moonlight were only two pieces to a much larger puzzle of representation and sociopolitical relevance. Then again, I’m sure my tone would be different if Moonlight lost.