but this place is just right.

At some point in my life I became a Podcast Person. I don’t know when this happened, or why, but let’s be honest, it probably had something to do with Serial. It was a good podcast, vaguely groundbreaking in its own way, a modern spin on Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line for the ears. It turned a reporter into a detective, and it turned Reddit into the world’s noisiest anonymous tip line, and in an unexpected twist befitting the form, paved the way for literally hundreds of glossy, narrative nonfiction true-crime podcasts. While there have been many such shows in its wake — S-Town, Dirty John, and the one that was literally just called Crimetown, to name a few — and many have been genuinely compelling pieces of entertainment, when you zoom out and consider the ethics of it all it’s hard not to feel uncomfortable. For all its Southern Gothic pretensions, S-Town is a show that outed a person who died by suicide and brought unwanted public attention on a random rural town full of real people. Missing Richard Simmons, an ostensibly lighter variation on the theme, was the most endearing and heartwarming piece of entertainment ever created by a man who was openly stalking Richard Simmons. Some of these shows are grim to the point of morbidity, while others sensationalize the non-grim, and the vast majority engages in the journalistic malpractice of strategically withholding information in ways that cause listeners to suspect innocent people of foul play. (For a more pointed and funny critique than I could ever muster, listen to The Onion’s parody of the genre, A Very Fatal Murder.)

But once you’re a Podcast Person, you are a person who listens to podcasts, and you have to keep finding new material to feed the gaping hole in your brain that can only be filled by recordings of people talking. This is harder than you might think it would be, as the other main form of podcast, the People in a Room Bantering genre, is rarely very good, either. If the banter is less interesting than the conversations you can actually participate in, then what’s the point; if it’s more interesting, then you’ll probably end up feeling a little lonely afterwards.

Enter history podcasts, the only podcasts worth listening to. They open up a world populated by inconceivably gentle people relaying genuinely gristly stories, full of strange characters and twists more surprising than they are forced. By their very construction, these shows are divorced from current events, but at their best, manage to humanize the dead and forgotten, connecting subtle truths about the past to the way we live our lives today.

In the beginning, there was Rome. Or rather, The History of Rome, a podcast started by a guy named Mike Duncan in the long-ago year of 2007. The first few episodes are rough — think an awkward dude stiltedly reading his undergrad history papers into his laptop’s microphone — but after a couple dozen episodes, something happens. Duncan becomes confident, fully at-ease with his own good-natured dorkiness. His words sound more natural, as if he wrote them to be spoken aloud on the microphone. The microphone, too, is different; presumably he went to Best Buy and bought himself a real one. By the time Julius Caesar is heading home from his conquests to crown himself Emperor, Duncan’s even mastered the art of cracking jokes. The podcast becomes a sensation. I have no idea how to quantify this, other than to say that the guy got a book deal out of it, and the book became a New York Times bestseller.

What made The History of Rome so great — and separated it from, say, Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History, the granddaddy of all history podcasts — was that Duncan didn’t over-dramatize or sensationalize his subjects. Instead, he re-examined established narratives, digging into the why behind history’s portraits of emperors like Nero and Caligula as total monsters (Nero was basically a hipster who hung out with the lowest in Roman society — gladiators and actors — while Caligula made the mistake of spending public funds while cutting taxes) and guys like Constantine as so-called Great Men of History (yes, he converted the Empire to Christianity, but that was an attempt to get a huge, polytheistic empire on the same page, plus he had his wife and oldest son killed, and that ain’t great). What emerges from the show is the sense that, even if they didn’t have electricity and thought you could make kids learn to read and write by physically threatening them, the Romans were as complex and nuanced a civilization as our own, its citizens just as beholden to the whims of tradition and social niceties as we are today.

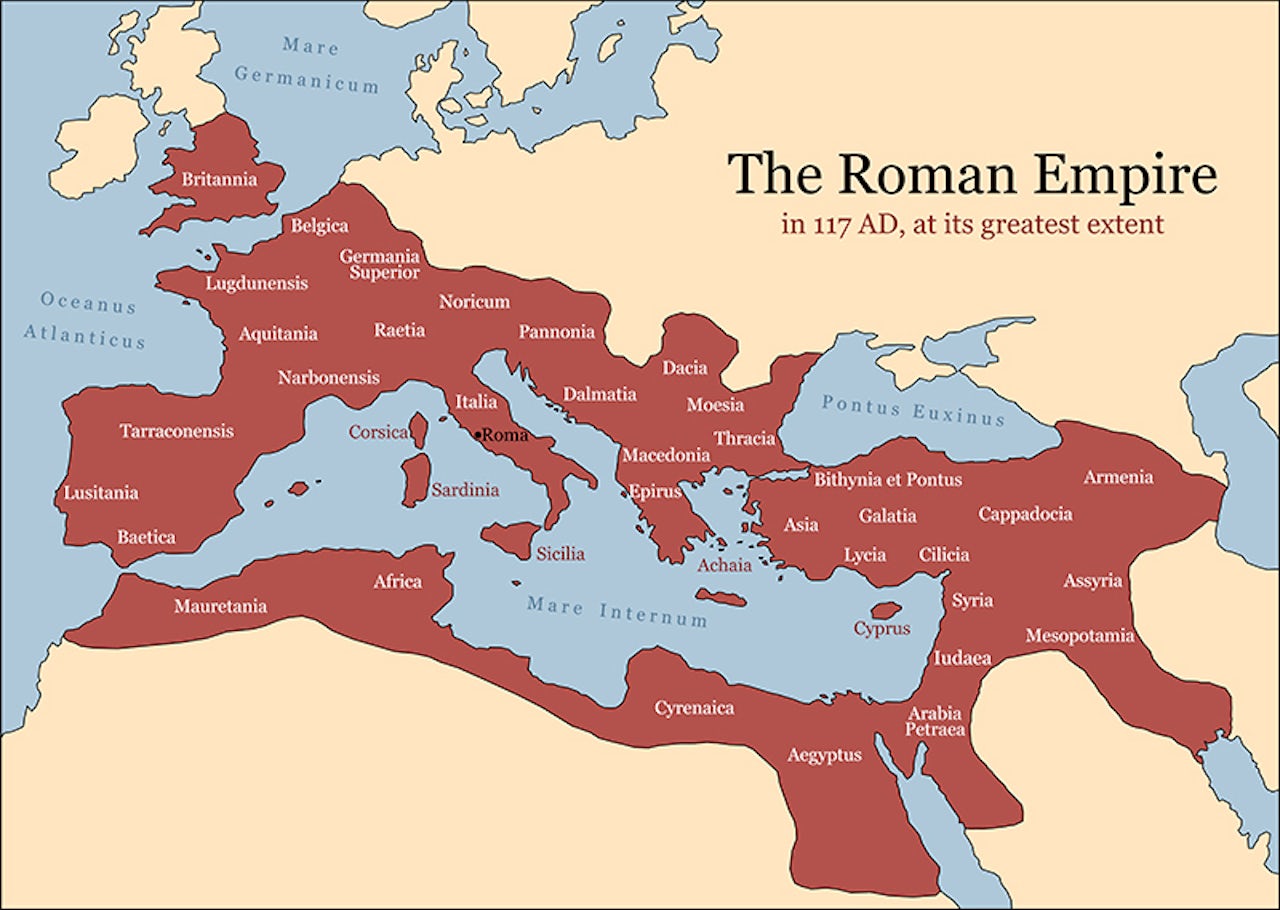

Just to refresh your memory, the Roman Empire fell into decline because it got big as hell. The Romans would conquer a region — preferably some place with an existing governmental infrastructure — simply by showing up with a big army, maybe fighting a few battles, and then announcing to its people that there was a new sheriff in town now, and that sheriff was Rome. They’d then leave a few soldiers behind, kick back, and collect tax payments from their new debtor state. But continuing this pattern for generations spread the empire too thin, and the task of actually keeping places as far-flung as modern-day Morocco, Great Britain, and Armenia under their control proved to be a logistical nightmare. As groups such as the Huns, the Goths, and the Vandals took turns invading one part of the empire or another, the Romans just sort of gave up, slowly leaving their protectorates to fend for themselves. The regular people left behind took what the Romans brought — their religion, their language, their governmental structures — and used it to forge cultural identities of their own.

This, in a sense, is what happened to history podcasting after Mike Duncan ended The History of Rome in 2012. He’d reached the hazy point in history — around 500 A.D. — where the empire was effectively based out of Constantinople, everyone involved was nearing the Middle Ages, and honestly, five years seems like a long time to devote to a single subject, so who can blame him for moving on? But just as the German, French, British, Egyptian, Byzantine, and a whole host of other cultures emerged from the ashes of the Roman Empire, so did a wave of more specialized podcasts, picking up where Duncan left off.

“I liked pretty much everything about The History of Rome,” says Robin Pierson at some point in the first episode of The History of Byzantium, proceeding to list off everything he loved about Duncan’s defunct podcast and then explaining he’d liked the show so much that he decided to pick up where he left off. The History of Byzantium proceeds to document the ashes of the Eastern Roman Empire as they smoldered for a millennium in Constantinople before being snuffed out around 1500. Where Duncan sounded like an enthusiastic guy at a bar talking your ear off about Rome, Pierson is milder, managing to make his half-hour dispatches from a past full of assassinations, brutality, and conquest take on a sedative effect. This is not exaggeration — if you are a person who falls asleep to podcasts, I cannot recommend The History of Byzantium strongly enough. He has a penchant for audibly cringing as he describes a particularly evil deed committed by one of his subjects; sometimes, he simply sighs at them like an exasperated parent. It is a very good podcast.

Where Duncan was a rockstar with enough of an audience to take a sponsorship from Audible, Pierson comes across as just somebody who’s trying to distinguish themself within their scene. In lieu of ads for products, many of his episodes begin with endorsements of his own podcast from other people who have history podcasts, and the episodes close with Pierson urging his listeners to check those other podcasts out, too. He has big-upped history-comedy podcasts, historical fiction podcasts, podcasts on war, podcasts on the time before Rome, and many on the time after. No one dares tackle Rome again. Many of these shows post new episodes infrequently, while others simply ended without notice. As someone with hard drives full of half-finished and just-only-started projects, all of which I vowed to pick back up only to never get around to it, I feel a kinship with these once-podcasters.

It’s through Pierson’s plugs that I found my new favorite history podcast, The History of England. Similar to The History of Byzantium, the show’s host, David Crowther, announces right at the top of the first episode that he’ll be picking up where Duncan left off, but in Anglo-Saxon Britain, which at the time was full of very short people who lived in tribal villages before being very quickly becoming overrun by — and intermixed with — taller, meaner, and more hierarchically-minded warrior tribes traveling from Germany. Like Pierson, the British Crowther makes all the bludgeoning go down with the force of a pillow, but injects a dose of levity, treating every new king, battle, and slash as if it were all part of a big Monty Python sketch. As he frequently reminds listeners, he records his show in a shed behind his house.

Many, but not all, of these podcasters are amateurs, poring through books, publicly available primary sources, and (probably) the odd Wikipedia page as they work tirelessly to compress massive amounts of historical data into tidy, bite-sized narratives. Pierson was a part-time TV critic before he started The History of Byzantium, while the creator of a show on early modern Europe works as a research technician in Rhode Island. There are exceptions to this rule, of course — Philip Harland, who does a podcast on the history of religion, is an actual Religious Studies professor — but for the most part, these are simply humble nerds, enthusiasts whose passions have bled over into side-projects.

History, in its basest form, is non-ideological. The people who did stuff that ended up changing the world didn’t do what they did so that we’d talk about them today; they did it because it seemed like a good idea at the time. They do not have anything to say about the way we live our lives today, because they are dead. If you went back in time and informed Cato the Elder, the Roman general and conservative public statesman, that one day he’d be the namesake of a think tank funded by the Koch brothers, he would literally have had no idea what you were talking about (and also, given that you would be speaking a language that did not exist and not wearing a toga, he might be freaked out and try to stab you or something). However, we inevitably interpret historical events through the lens of our own ideology. Modern historians have generally put more stock in written histories from antiquity — despite the fact that, as many of these podcasters discuss, such histories were essentially works of propaganda disseminated by one institution or ruler as a way to glorify themselves and shit on their enemies — than those passed down through oral traditions. This has the unfortunate side-effect of marginalizing the histories of peoples who didn’t bother writing things down, and given that some Western historians have used this as a cudgel with which to dismiss non-Western cultures from asserting the legitimacy of their own cultural histories, it’s hard not to think that there’s something deliberate about it all.

It’s ironic, then, that the oral tradition of historiography is enjoying a digital renaissance. Many of these podcasters derive at least a good chunk of their income from telling the world about history, and there’s something to be said for the way that, in their hands, jumbles of names, dates, and events fall into narratives that, if not always completely accurate, at least get the point across in the coziest manner possible.

As for Mike Duncan, after he wrapped up The History of Rome, he went to grad school and got a graduate degree in history. His book about Rome sold well enough that he got an offer to write another one. He now lives in Paris, spending his days in various archives, conducting research for his upcoming volume on the French Revolutionary general Marquis de Lafayette. When he began The History of Rome, he worked as a fishmonger. Now, he’s a real historian. He’s also over 200 episodes into his new podcast, one tracing the conflicts that led up to the modern world. Its name? Revolutions.