One of my favorite pastimes is to think of every bad, awkward, or embarrassing thing I’ve ever done and let them tumble around in my head until I am prostrate on the floor. The aggregation of all these bad feelings — I said something dumb, my friends are ignoring me, my toes are weird — typically leads to catastrophic ones: I am awful, nobody likes me, I will die alone because of my weird toes. My friend who is also named Leah says not to let yourself think about any unpleasant interaction for more than seven seconds, which is very good advice; currently I am probably at around seven days, but sometimes seven years.

I have become dedicated to finding ways to separate myself from these annoying, circuitous, and potentially destructive emotional loops. Distractions help: talking to a friend, going for a walk, or even, extremely unfortunately, going to the gym. But distractions are not really enough. What I really seek is distance and, eventually, detachment.

I wrote about this a little bit last year when talking about the concept of envy, another thing that dogs my dog brain. Drawing from philosophy and psychological theory, we can learn that envy is woven into our DNA, therefore there is nothing we can do about it, and we cannot feel personal guilt about something we cannot control. I was pretty happy with this conclusion, and it ameliorated my envy for at least 48 hours.

But what of feeling bad in general? That everything is wrong all the time, that every minor mistake or event or interaction is a sign that the universe is against you: this is called catastrophic thinking. I simply love to think this way, and very little can stop me.

Unfortunately, there is not a lot of reading material on catastrophic thinking from the philosophers and psychological theorists I trust, although there is this forum post on the sadly named website beyondblue.org. As a result, you will just have to have faith in my description of it: that the worst-case scenario is the best and only way to think about things — one must suffer to survive — even as it further corrodes your mind and spirit.

Two things that have lately been in the news are Boeing and Chernobyl. Boeing, because a faulty sensor on its 737 Max airplanes caused two flights to crash, killing everyone on board, and despite scads of whistleblower testimony about the sloppy construction of its planes and lack of safety oversight, the company has not fully taken responsibility for the failures of one of its most-touted products. And Chernobyl, because there is a new HBO show about it (Chernobyl), and the two episodes that I have seen were very good. Both are examples of how a crisis can be made worse by the people who are supposed to be in charge of it.

In Boeing’s case, the company has exhibited a stunning degree of incompetence in addressing its failures. Despite the overwhelming evidence that its planes were probably death traps, and even after one of them turned out to be one, official communication from the company has left open the possibility that its planes crashed because the now-dead pilots somehow mismanaged a system that was designed to fail and, in the process of failing, work against them. And even though this led to a fatal crash in October 2018, and Boeing knew it, the company still kept the planes in flight. The Federal Aviation Administration did not object, but it also did not look at the planes closely enough to begin with, and another one crashed in March. Three-hundred and forty-six people died as a result of both crashes.

When the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine melted down in April 1986, official blame was ultimately placed on an engineer named Anatoly Stepanovich Dyatlov. According to official accounts, Dyatlov violated safety procedures to conduct a routine experiment for the government. And even though Chernobyl was built with many inherent and dangerous flaws for which many people and official bodies were responsible, and even though one of its nuclear reactors experienced a partial meltdown in 1982 that was kept secret by the government, only Dyatlov and six other plant operators were sent to prison. It is still unknown how many deaths Chernobyl directly and indirectly caused; the number is estimated between 4,000 and 200,000.

The Chernobyl disaster and the Boeing crashes are both are examples of how a crisis can be made worse by the people who are supposed to be in charge of it.

The Boeing crashes and Chernobyl both happened not because one person or even many people did something wrong but because one person did something wrong and a million other things went wrong, too. There’s a term for this, and it’s called a “normal accident.” As the Yale sociologist Charles Perrow writes in his 1984 book, Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies, “It is normal for us to die, but we only do it once. System accidents are uncommon, even rare; yet this is not all that reassuring, if they can produce catastrophes.” Some other examples of normal accidents include the partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in 1979, the Challenger explosion in 1986, and the crash of ValuJet 592 in 1996.

Normal accidents might seem like acts of God but are actually the furthest thing from it. Catastrophes are never simple nor unemotional, but they can be made mundane, and what is more mundane — more normal — than something going wrong? “Most high-risk systems have some special characteristics, beyond their toxic or explosive or genetic dangers, that make accidents in them inevitable, even ‘normal,’” Perrow writes. Statistically, and regardless of the human cost, such mind-rending disasters are actuarial guarantees: if the systems can exist, they can, and will, malfunction.

This ordinariness can also be seen in the language that is used to describe a normal accident in its aftermath. Writing about the demise of ValuJet 592 in a 1998 Atlantic article, the journalist William Langeweische described the bureaucratic patois of the accident’s task force: “The investigators set up shop in an airport hotel, which they began to refer to as the ‘command post.’ The language is important. As we will see, similar forms of linguistic stiffness, specifically engineerspeak, ultimately proved to have been involved in the downing of Flight 592 — and this is a factor that the NTSB investigators, because of their own verbal awkwardness, have been unable quite to recognize.”

Langeweische later recounted the Senate testimony of an FAA administrator named David Hinson, in which the man sounded like “an unrepentant Prussian: “We have a very professional, highly dedicated, organized, and efficient inspector work force that do their job day in and day out,” Hinson said. “And when we say an airline is safe to fly, it is safe to fly. There is no gray area.”

A similar tone can be seen in Mikhail Gorbachev’s address to the Soviet people on May 14, 1986, a little more than two weeks after Chernobyl was decimated. “As you all know, a misfortune has befallen us,” Gorbachev opened, immediately punting blame from his government. From there, he advanced to lying. “In view of the extraordinary and dangerous nature of what happened at Chernobyl, the Politburo took charge of the entire organization of the work needed to ensure the speediest possible action to control the accident and limit its effects,” he said, eliding how the government downplayed the disaster, delaying evacuation from the surrounding town for 18 hours, telling worried people that humans could survive being exposed to potentially lethal levels of radiation, and decreeing that the milk from irradiated cows was safe for children to drink.

Ordinariness can also be seen in the language that is used to describe a normal accident in its aftermath.

Such formal, antiseptic language seems even more galling today when contrasted with social media’s frenetic lack of ceremony. Amid outcry, Boeing has established a dedicated page on its website for “the latest information, updates, and statements on the 737 Max,” as if it were a new and exciting product; a statement on the page from the company’s CEO, Dennis Muilenberg, emphasizes how this has been a “heart-wrenching time” for him and that the company is “deeply saddened by and sorry for the pain these accidents have caused worldwide,” even though those accidents were caused by its planes and, in part, the actions of employees for whom he is responsible.

Normal accident theory is fascinating for the space it creates between the all-consuming pathos of catastrophe and the cold semantics of crisis management. It is a process of rationalization and distance that carries the intrinsic dangers of minimization, blame-shifting, clinical detachment; more sinisterly, it can allow those who bear responsibility for disaster room to protect their interests. But it is also an idea grounded on Earth — in the way some might turn to religion after a cataclysm, the pragmatist can turn to normal accident theory. The way the word “normal” is used has a counterintuitive power — the most unbelievable thing is just how normal extraordinary events are. It is a compelling account of a cliche: essentially, shit happens.

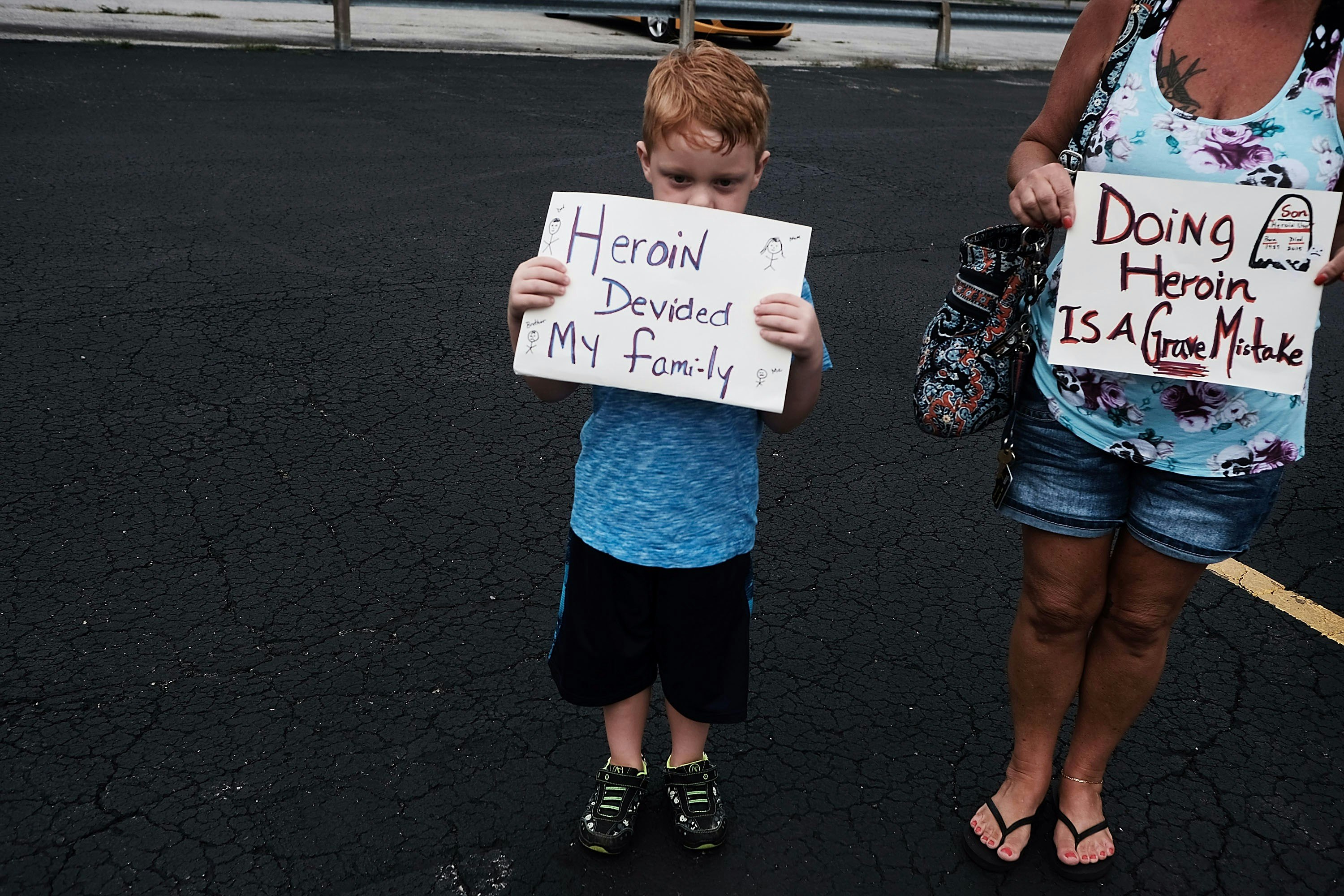

A young friend of mine was recently diagnosed with depression. I have found myself in the interesting position of managing my own condition while advising him on his. He often asks me if certain feelings are normal, or if I have ever experienced them. Did I ever feel like giving up? Sure! Have I ever felt suffocated by my own existence? All the time! Is some combination of therapy and medication worth it? Oh my, yes!

It’s been illuminating to revisit the tracks of my own depressive journey while guiding him through his. I wasn’t formally diagnosed until I was 25, but I’m sure if I had the choice I wouldn’t have shown up to my own birth. On average days I might feel like I’m trying to separate grains of rice with hands covered in honey, on bad ones it’s as if my brain has been dipped in sulfuric acid and I can hear it sizzling away into a state that’s right before nothingness — my depression would never grant me the reprieve of making my brain disappear completely. The enduring punishment is that it is always there and always conscious and there is nothing that can cure it, not even weed.

Depression is the most common cause of disability in the world, and yet we do not know what causes it. A recent study said that women, who have higher rates of depression, might be more susceptible to it because their brains are more likely to experience inflammation, which can dull their reward-processing centers. This leads to anhedonia, or the loss of the ability to feel joy from one’s favorite activities; in some cases, especially among the young, those with this condition do not respond as well to antidepressants.

My depression would never grant me the reprieve of making my brain disappear completely.

Depression may be brought on by an inciting incident, but its existence is allowed by some mystical combination of environment, age, family history, experience with medication, the apocryphal “chemical imbalance,” or, if you’re me, all of this plus the combination of being Irish and Jewish. We know that there’s some mysterious causation in the mind-brain connection, but we don’t know what that is. As the neuroscientist Elliot Valenstein said in Andrew Solomon’s canonical depression book, The Noonday Demon: “Mind cannot exist without the brain, but mind can have influence on the brain. It’s a pragmatic and metaphysical problem whose biology we do not understand.”

Many thinkers, from Foucault to Didion, have argued that depression is a sane reaction to an insane world. The Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing (who became known for his anti-psychiatry stance) theorized that schizophrenia in particular was a response to illogical societal conditions. As the sociologist Richard Sennett wrote in an appraisal of Laing’s work: “Society makes insanity, [Laing] argued; sanity is a condition in which people are willing to obey social rules, even if the commands are inhumane and irrational. The rebels are labeled insane.”

Depression is inevitable in society. Among billions of people, many are going to have fucked-up brains; unfortunately one is me, and now my young friend. But I wonder if depression, in some non-parallel extrapolation, can be thought of as its own kind of normal accident: a guaranteed cataclysm in the dark, complicated system of a mind that cannot be prevented, only managed after the fact. In this way, the cause of my depression can remain mysterious and relatively unimportant — it happened, for reasons social or biochemical or both, and the job now and maybe forever is dealing with the fallout, managing my own crisis.

This flips the distancing language of an executive or government response to a disaster in an interesting way. Muilenberg’s response to Boeing’s woes is at best insensitive; Moscow’s non-response to Chernobyl added another layer of devastation to an unimaginable event. In the cold statistical ice bath, disasters are handled as if to minimize them; a convenient scapegoat is often found to receive any outstanding ire. Perrow stresses that the immediate response to a normal accident is crucial. A bungled recovery can be the difference between a Chernobyl and a Three Mile Island: one an international tragedy having reverberating effects for decades, the other mostly forgotten.

The inept and bloodless management of large-scale disaster is not a recommended blueprint for the next frontier of depression management, but allow me the extrapolation. Thinking of depression as a normal, inevitable, and inexplicable catastrophe in an inscrutable system creates distance from it — the ability to climb out of my personal disaster and see the world clearly, and not assume the worst is destined to happen always.

I will never be able to untangle my mind or fully curb my brain’s assiduous desire to assume the worst in every situation. But I can seek to better understand and manage these things, and know that my condition is not unique, that this kind of suffering is universal and expected. If nothing else, it has been a relief for both me and my young friend to tell him what he is experiencing only means that he’s normal.

Get Leah Letter in your inbox.