One thing they never tell you about being a celebrity is that it’s impossible to just be. There’s always a chance you’ll get recognized by someone, somewhere, and if that happens, there’s no other option than to stop acting like yourself and start acting like the person people think you are — or, frequently, the person that you want people to think you are. This struck me on a Monday afternoon in Charlotte, North Carolina earlier this year, as I stood outside a community center watching the rapper DaBaby trying to prevent a crowd of children from seeing that he was holding a lit blunt. While taking a smoke break on the set of a music video for his artist Rich Dunk’s song “High School” that DaBaby was co-directing, the kids at a nearby elementary school had started lining up outside to take the bus home only to take notice of this massively popular local rapper mere yards away from them.

Dutifully, DaBaby held the blunt behind his back, smiling and waving at the kids as they were screaming and crying and oh-my-God-it’s-DABABYYYYYY-ing, working themselves into a chaotic, youth-sized frenzy. I worried that there was a distinct, perhaps inevitable, possibility that they wouldn’t be able to contain themselves, and run en masse over to DaBaby to give him hugs or ask for his autograph or do whatever else it is that eight-year-olds do these days. And if this happened, the blunt would have nowhere to hide.

To be clear: DaBaby, whose given name is Jonathan Kirk, did not want to poison the minds of Charlotte’s children by having them see him smoke weed, and he definitely did not want them, or the adults minding them, to smell it. So he smiled, sheepishly, and tried to be enthusiastic enough with his free hand so that the kids would focus on that one and not the one behind his back. Before all hell had a chance to break loose, the bus came and the kids hopped on, passing the 27-year-old rapper close enough for one last goodbye. When I asked him how often incidents such as this one happen, he told me, “All the time, man.”

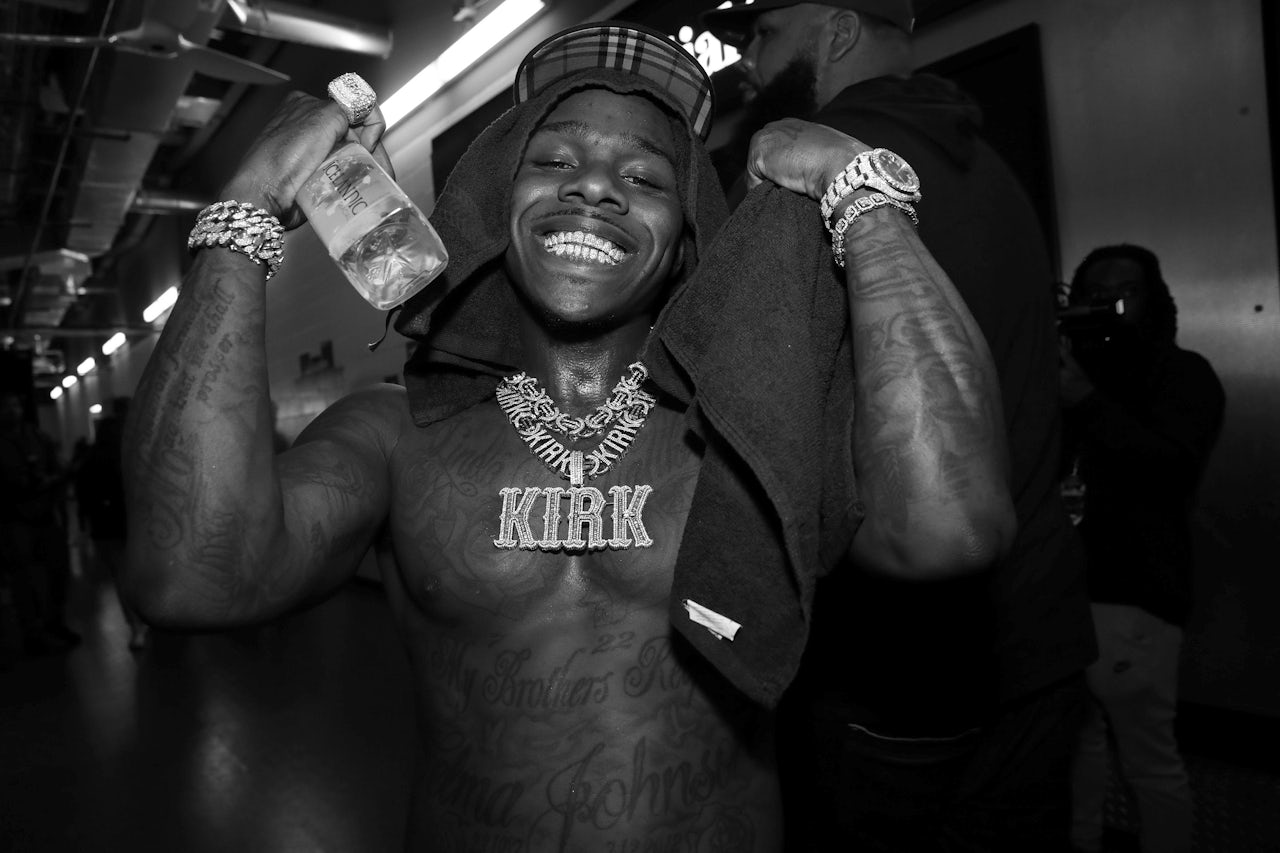

Over the past year or so, DaBaby has ridden a stunning wave of momentum from local prominence to national renown. At the beginning of the year, he did not have a record deal; in October, his album Kirk — his second for Interscope, which signed him in February — debuted at number one, causing literally every song from the record to enter the Billboard Hot 100 chart simultaneously. He’s made hits with Megan Thee Stallion, J. Cole, Chance the Rapper, and Nicki Minaj, and has done remixes for mainstream stars such as Lizzo and Lil Nas X. A couple months after I spent the day with him in Charlotte, he was the musical guest on Saturday Night Live, rapping while performing choreographed dance routines and appearing in a sketch alongside host Jennifer Lopez. Next year, he’ll be hitting the festival circuit — he’s playing the Bud Light Super Bowl Festival in Miami alongside Guns ‘N’ Roses and DJ Khaled, as well as the Dutch festival Woo Hah and Dublin’s Longitude Festival — and his hit single “Suge” will be up for a pair of Grammy Awards.

A couple hours prior to the blunt incident, I was sitting in the backseat of a white Lincoln that belongs to DaBaby’s manager Carter, waiting for DaBaby to arrive at the site of the video shoot, while listening to DaBaby on the stereo. Carter is a former local rapper who transitioned to managing DaBaby full-time, and has taken to his new role with aplomb. His focus with DaBaby, he told me, is to “show the world he’s the best.”

Showing the world that DaBaby is the best, it seems, involves making lots and lots of phone calls, and as he left his car to take one, I realize that we haven’t been listening to DaBaby’s music on Carter’s phone as I’d assumed. We’d been listening to the radio, and the radio plays a lot of DaBaby: In the span of 20 minutes or so, the local Charlotte station played his singles “Babysitter” and “Suge,” as well as collaborations he’s done with Chance the Rapper (“Hot Shower”) and Post Malone (“Enemies”). Much like how it was with 50 Cent in 2004 or Lil Wayne in 2008, hip-hop radio is basically a DaBaby Pandora station these days.

That evening, DaBaby took me to his office, a glass-walled multi-room suite he rents from a coworking space downtown. Massive, gold-framed images of his album and mixtape covers lean up against the walls; a custom-made rug of his logo, a grinning cartoon baby, sits in the middle of the grey carpeted floor. “If I put that [for sale] on the internet right now, [fans would] go, ‘How much?’” he speculated. Most of the other suites in the building belong to tech companies, he said, which he finds amusing — especially since, as he pointed out, “This is the biggest office in the building.” His entourage shuffled off to an alcove with some black couches set up around a TV to play some Madden, while DaBaby made a bee-line for the fridge, where his mom dropped off some of her home cooking for dinner: roasted potatoes, carrots, cornbread, corn on the cob. “Oh my God,” he said, diving into the meal.

When we spoke, he’d been bopping around the country doing concerts at colleges, playing multiple shows a week sometimes squeezing in two shows in different states in the span of a single day, while making media appearances and recording a blitzkrieg of guest verses in his portable studio. “That’s why I’m so skinny right now. I don’t have time for the gym. I need to eat [more],” he said, fishing a roll of floss out of a designer shoulder bag that also contained what must have been a four-inch thick stack of $100 bills. DaBaby then proceeded to floss on and off throughout our conversation, picking little bits of his mom’s home cooking out of his teeth to keep the layer of white gold and diamonds covering them pristine. (He got his teeth done, he told me, “When Interscope cut my check.”)

DaBaby and his mother are particularly close, in part because he was the youngest child in a family of three boys. “I was her baby,” he said of his mom. He now has a daughter of his own, a two-year-old he raises with his longtime partner, Meme. “At two, their personality comes out,” he said. “They can tell you how they feel.” (According to The Source, DaBaby also serves as a father figure to Meme’s six-year-old son and that the pair are currently expecting another child.)

As a kid, DaBaby was energetic and outgoing — “the life of the party,” as he put it — but his primary interest, he said, was money. When his father, from whom his mother divorced when he was young, would send money for the kids, he’d ask for his share “in all ones. I’d walk around with a bank roll.” He remembers being in elementary school and being handed a list of potential careers in class. After finding out their salaries, “I was like, ‘I don’t want to be none of that,’” he said. “But I’m not going to be no one.’”

After graduating high school, he spent two years at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, which he hated. “I did that shit for my parents,” he said. “They really wanted me to go to school.” His aborted stint in college, however, did yield one dividend: it helped him realize he was extremely good at rapping. “Every time I met somebody that would have a mic and a computer and some studio equipment, at first they’d let anybody come vibe with them. But then I go and make a song with them, and I’d be better than them. After a while, they’d quit wanting to do songs with me.” Eventually, DaBaby decided to copy these set-ups and learn how to record himself.

Once he moved back to Charlotte, DaBaby spent a couple years “getting money” (he declined to go into more detail about what he meant by this) before dedicating himself to music. “I wanted everything to be mine, and I wanted everything to be from scratch,” he said. “I started off getting all my beats made right there in front of me” (an anomaly in an age when producers frequently collaborate with rappers by sending tracks back and forth via email). He’d been rapping in earnest for a month when he recorded his first mixtape, titled Non-Fiction, and released it under the name Baby Jesus. A few mixtapes later, he changed his name to DaBaby — “Just call me DaBaby but leave out the Jesus / I turned all the fuck n—gas into believers / I switched up my name for political reasons,” he raps on the first track of his 2016 tape God’s Work Resurrected. He worried the original moniker might cause “extra controversy,” he told me.

“You see the controversy motherfuckers make about me already,” he said. “Imagine if I had [Baby Jesus] attached to everything.”

At this point, things went momentarily off the rails. I told DaBaby that I thought the Memphis rap group Three 6 Mafia had done well for themselves despite having an overtly sacriligeous name, to which DaBaby said, “I don’t fuck with him — the devil, that is.”

Now, the interview had been a lively affair. We had been joking back and forth, trading little nuggets of southern rap trivia between more formal questions and answers, and at one point, he paused our conversation to pantomime how he used to steal steak out of the grocery store by hiding it in the front of his underwear. And so, in the moment, it seemed perfectly natural for me to say, “Nah, the devil’s great!”

It turns out that this was not, in fact, a good idea. DaBaby looked shocked, and cut me off as I was mumbling a half-hearted explanation/apology to solemnly say, “The devil ain’t welcome here, brother.” Thankfully, our interview time was almost up, and we managed to get through our final few minutes together despite the fact that I’d completely drained the air out of the room by offending DaBaby’s theological sensibilities.

Two days later, it was communicated to me that my offhand comment also had the effect of causing DaBaby believe that I was a Satanist, and that he would be pulling out of the photoshoot that was scheduled along with our interview. Weirdly, the entire affair only caused me to respect DaBaby even more. I admire people who stick to their principles, even if those principles only reveal themselves because of me acting like a total idiot.

Shortly after the Non-Fiction period, DaBaby started working to create a self-perpetuating cycle of hype. “I got with the hottest DJ in the city and the hottest cameraman at the time,” he said, with the intention of producing “Content, non-stop. Just content, content, content.” He’d record a song, have his DJ play it in a strip club, have his filmographer record him throwing money as the song played, and then would personally edit the footage on his laptop and post it to Instagram.

Over time, his music videos became looser, a bit more fun, stretching the self-serious conventions of street rap by injecting an element of self-awareness into his work. In the 2017 clip for his song “Pull Up Music,” he undercuts a fairly standard-issue dealing-drugs-in-front-of-the-trap-house scene to lasciviously tongue the banana clip of an assault rifle. The music video for his 2018 rework of Drake’s “In My Feelings” begins with him getting yelled at by a woman outside of a gas station and ends with him handling gallon-bags of hay as if they were bricks of weed. By the time his breakout single “Walker Texas Ranger” hit YouTube on New Year’s Day 2019, he was driving a pickup truck off a cliff and doing kung-fu while wearing a cowboy hat, and vigorously humping the air while making faces implying that even he couldn’t believe the anatomically absurd imaginary sex he was having.

This approach, of treating one’s rap career as essentially an online multimedia project, was a novel one in North Carolina’s rap scene, a state which has not produced many rap stars. Superstar J. Cole, one of the few exceptions, had to jumpstart his career in New York. “It’s hard in North Carolina, because you’re talking about a state that’s not known for national artists,” said Rapper Big Pooh, half of the North Carolina group Little Brother, which spent the early-to-mid-2000s as one of the most popular acts in the hip-hop underground but never quite managed to cross over to the mainstream. The state is, as he put it, a “melting pot” of influence due to the large number of universities and corporate headquarters in the state which draw in out-of-state transplants, as well as its cities’ popularity as a stop for artists routing their East Coast tours from New York to Atlanta. For years, Pooh said, “North Carolina really didn���t have a ‘sound.’ I think that prohibited artists from North Carolina from doing more.”

What allowed DaBaby to break out of Charlotte and go national, his longtime friend Trap told me, was how the rapper acted like a celebrity even before he was one. “From day one, he was doing star shit,” he said. His crew would arrive at venues wearing matching outfits and holding signs, as if they were representing an artist who’d already moved beyond the local scene. “It wasn’t just showing up at a club and hoping someone was going to spot you from your song. You were going to spot that n—ga out.”

In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that DaBaby is a terrible driver. I discovered while riding along with Carter in his Lincoln, as we attempted to keep up with DaBaby as he headed out from the video shoot to his office. On the highway, DaBaby’s white Dodge Charger veered from lane to lane, occasionally flashing the left turn signal when he was going right and the right turn signal when he was going left. At one point, DaBaby cut off an entire lane of traffic to take an exit so that he could make an unannounced detour to go to an apartment complex, at which he parked and blasted his own music instead of getting out of his car.

You might say that DaBaby’s driving style mirrors the way he operates professionally. “I’m the hardest person to get shit done with,” he said, “because I’m always doing five things at once.” At this point, he posts multiple clips to his YouTube channel a week; they might be interviews, footage of him performing on a talk show (he’s recently done Fallon and Desus & Mero), as well as his own music videos or those uploaded on behalf of proteges such as Rich Dunk, 704 Chop, and Stunna 4 Vegas. This steady drip of content both provides him both with revenue — you’d be hard-pressed to find a music video on there with less than a million views — and creates an algorithmic feedback loop that helps maintain his relevance in the fickle world of hip-hop.

While much of DaBaby’s appeal stems from his frenetic rap style and sense of humor, he brought a disarming gravitas to the introductory track for his most recent album, Kirk. In the song, he discusses the loss of his father (a photo of whom is on the record’s cover), his mother’s bout with cancer. He tells his brother, “Like I won’t give up all I got to see you happy,” over a beat produced by his touring DJ, DJ K.i.D., whose sputtering drums and celestial organs mirror the emotion that DaBaby displays in his lyrics. It’s an ambitious track, and perhaps his best.

DaBaby has spent much of this year attempting to shake off a reputation for starting trouble. In July, he was sued by a music venue for canceling a concert after his bodyguards assaulted a fan; earlier this month, DaBaby countersued, claiming that the venue had failed to honor a clause in the show contract providing for security guards (through a P.R. rep, DaBaby declined to comment on this matter, citing the fact that the case is ongoing).

And then, there’s what DaBaby’s team calls “the Wal-Mart thing.” The Wal-Mart thing is this: On November 5, 2018, a Huntersville, North Carolina police officer on a routine security check of a local Wal-Mart heard gunshots from inside the store, and soon discovered a 19-year-old man named Jalyn Craig had been shot in the stomach. According to a Facebook post from the Huntersville Police Department, Craig was pronounced dead on the scene and that “several other individuals were taken into custody as well due to an altercation.” Rumors began circulating among hip-hop blogs that DaBaby had been in the Walmart at the time and had shot Craig in self-defense after the young man had tried to steal his jewelry. DaBaby then appeared to confirm these rumors in a video he posted to Instagram Live, claiming that he’d been shopping in the store with Meme and their children when a pair of men pulled a gun on them and then implied he’d retaliated by shooting one of them. “Lemme see what y’all [would have done],” he said in the clip, adding that he believed security footage of the incident would vindicate him and that his fans ought to allow Craig’s family to grieve in peace.

In June 2019, DaBaby was found guilty of carrying a concealed weapon, a misdemeanor in North Carolina, in connection with the shooting. He is currently serving a year’s unsupervised probation. According to a statement from the Mecklenburg County District Attorney’s Office, the Huntersville Police Department opted “not to charge [DaBaby] further, as prosecutors could not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant did not act in self-defense.” (Voicemails left by The Outline with the Huntersville Police Department seeking more information on the matter went unreturned.)

Though his publicist cautioned me against bringing up the Wal-Mart incident to him, DaBaby sure as hell seemed to allude to it during our conversation. “I’d already been shot at before I got famous. Already’d justifiably shot somebody,” DaBaby told me, unprompted, during an exchange about the sudden rush of success that has defined his 2019. He quickly clarified, adding, “Like, before I blew up. This was years ago.” I asked him to elaborate, and he said, “If I didn’t do it, I probably wouldn’t be here. Definitely wouldn’t be here.”

Despite his outsized public persona, DaBaby is intensely private. “I don’t have a choice” but to be that way, he told me, “so I don’t have to bust nobody’s head.” His desire to remain as unobtrusive as possible even informs his choice of vehicle — while his Dodge Charger is certainly a nice car, it was merely one of many that I noted in the parking lot of the video shoot that day. When he hopped out of the Charger, he was wearing a grey Nike sweatsuit, socks, and a pair of black and grey slides that, if you weren’t close enough to make out the words “Louis Vuitton” on them, would have seemed downright pedestrian.

Once on set, DaBaby worked to center the attention on Rich Dunk, a relentlessly friendly kid with face tattoos who was skinny as a rail and had a single, gravity-defying dreadlock that shot directly up out of his head. Though DaBaby didn’t have a verse on the track, titled “High School,” he was starring in the video alongside Dunk as well as co-directing, and would eventually upload the clip on his YouTube channel.

True to the song’s title, the concept of the “High School” video was that Rich Dunk has been the man since he was in high school, and that part of him being the man has involved him relentlessly picking on DaBaby over the course of several years. The purpose of the shoot in the community center — itself a former school — was to illustrate this through shots of Dunk bullying DaBaby as he played a hapless teenage dork.

After overseeing a shot of Dunk holding court in a makeshift high school hallway, DaBaby entered an old classroom where the next scene would be filmed. He dug into a plastic bag full of props, laying out notebooks and pencils for all of the extras, taking care to arrange the notebooks by color despite the fact that they’d end up being open once the cameras were rolling. He then set an apple down at the desk where he’d be sitting, grinned, and said to no one in particular, “Teacher’s pet shit.” He absconded to a back office and emerged wearing his costume for the day: glasses, a Rick and Morty baseball cap, a collarless white button-up, and suspenders hooked into a pair of pleated pants that are so tight around his ankles that they might have been jodhpurs. “I should be a gangster nerd forever!” he said of the getup.

He and the production manager (Rich Dunk’s mom) then shuttled the extras into the classroom, where he started giving directions. “The more hand movements, the better,” he told them, pantomiming the note-taking, hand-raising, and cutting up that they’re supposed to be doing. As someone started passing out rubber bands to the extras, DaBaby joked, “Don’t throw them shits at the back of my head, I’m trying to clean up my criminal record.”

Once the cameras started rolling, the extras did their best to follow DaBaby’s instructions, behaving in the same not-quite-believable-but-good-enough way that you or I would if we were told to pretend to be a teenager in class. DaBaby, though, fully embodied his character. He waved his hand at an invisible teacher like an eager goofball, appeared crestfallen when he didn’t get called on, and looked shocked and perturbed when Rich Dunk stole his apple. To the extent that a grown man with a visible mustache, face tattoos, and diamonds in his teeth can believably pretend to be a child, DaBaby completely nailed it.